The Park Street School at the corner of Park and Hamilton Streets in Holyoke, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

The scene in 2017:

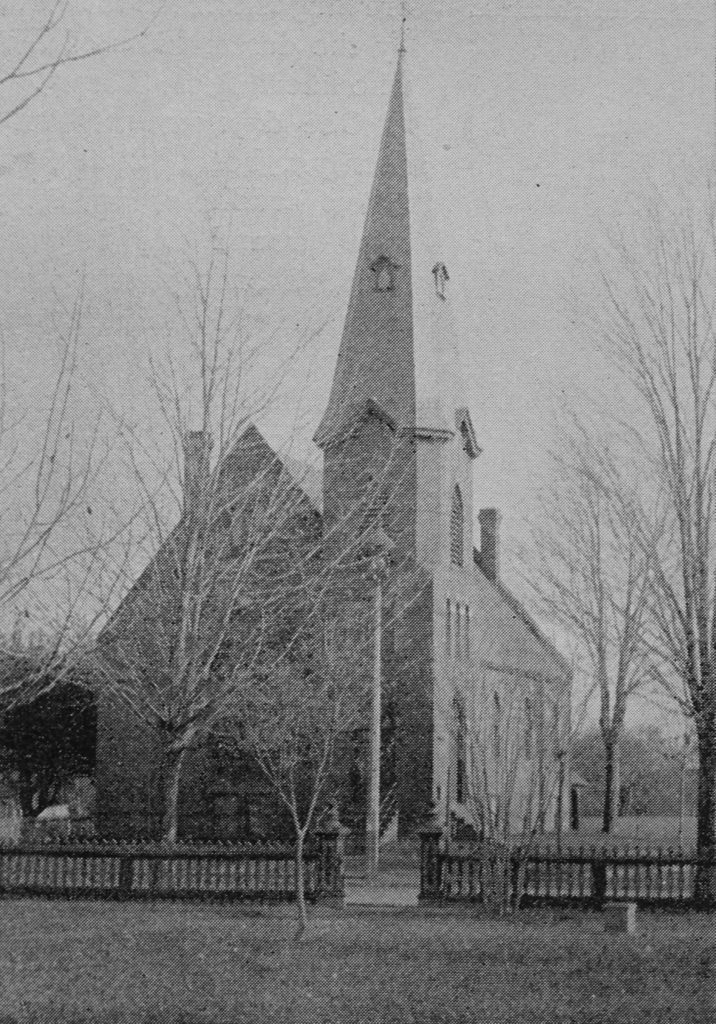

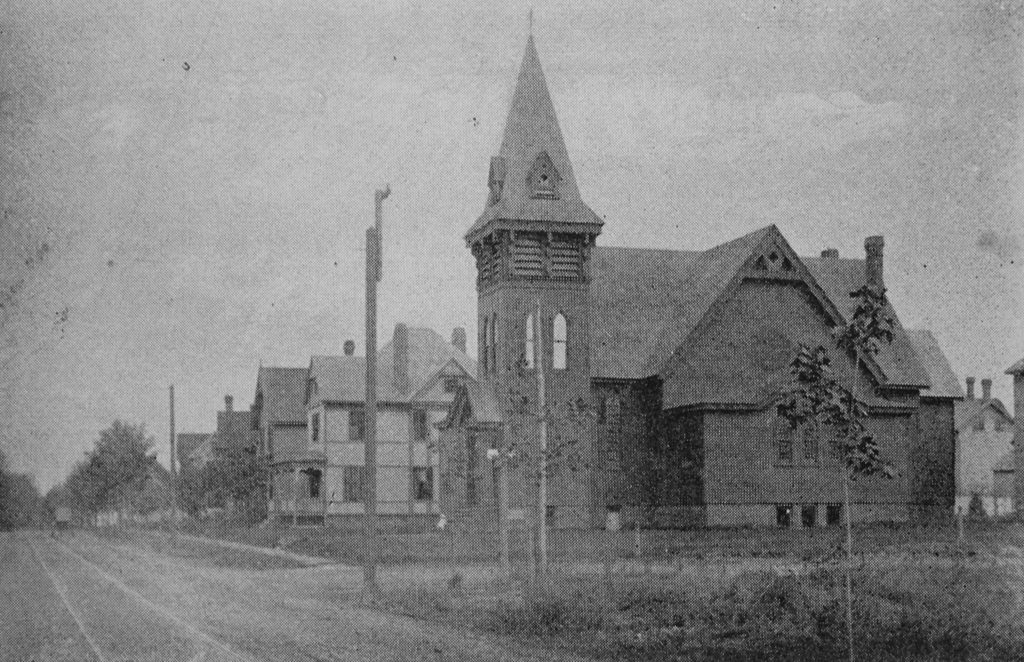

The caption in Picturesque Hampden identifies this as the Hamilton Street School, but it is actually the Park Street School, which is located just across the street from where the Hamilton Street School once stood. It is perhaps the oldest surviving school building in the city, and dates back to 1868 when it opened as a public school. Like many other buildings of this period, it had Italianate architecture, and it featured a symmetrical front facade with a tower in the center. Just beyond the school, on the left side of the first photo, was the Precious Blood Church, a High Victorian Gothic-style French Catholic church that was completed in 1878.

In 1875, the Park Street School played a grisly role in one of the deadliest, yet also one of the least-known disasters in Massachusetts history. At the time, the Precious Blood Church was under construction, and the parishioners, largely French-Canadian immigrants, worshiped in a temporary wooden church, located behind the right side of the school at the corner of Cabot and South East Streets. The wooden church, built in just a month in December 1869, had a capacity of about 800, and included a large balcony that could seat about 400. On May 27, 1875, the church was filled with some 600 to 700 worshipers for an evening Corpus Christi mass, but toward the end of the service a lace curtain, blown by a stiff breeze through the open windows, touched a lighted candle and caught fire.

The fire on the curtain quickly spread to the wall, and within minutes the building was engulfed in flames. Those on the ground floor of the sanctuary had a fairly easy escape route, through any of the three front doors of the church. However, those in the balcony had only a narrow stairway that led down to the front entrances, where the crowds from the ground floor were also trying to escape. One of the doors eventually became blocked by people who had tripped over each other, and firemen worked desperately to free people from this pile in what little time they had. In particular, future fire chief John J. Lynch – namesake of the former John J. Lynch Middle School – was noted for his bravery in rescuing survivors, and thanks to the efforts of Lynch and other firemen, the death toll was not as high as it otherwise may have been.

Within just 20 minutes of the curtain brushing against the candle, both the church and the adjacent rectory were completely destroyed. The next step was to recover and identify the bodies of the victims, and the Park Street School was converted into a morgue. The bodies were laid out here in the basement by the following morning, and friends and family members of the victims arrived to identify their loved ones. Many of the bodies were burned beyond recognition, and were only able to be identified by clothing, shoes, jewelry, and other personal effects.

The total number of deaths in the fire has been variously listed as low as 74 and as high as 97, although the lower figure is probably closer to the true count. The language barrier likely contributed to some of the discrepancies, and in some cases spelling variations of the same name were apparently recorded as two different people. Either way, though, it ranks among the deadliest fires in the history of the state. By way of comparison, the Great Boston Fire of 1872, which occurred less than three years earlier, destroyed 776 buildings in densely-populated Boston, yet had a death toll of about 20 to 30, only about a third of that of the Precious Blood Church.

At the time of the fire, the new Precious Blood Church was already under construction, but work had not progressed much further than the basement. Nonetheless, two days after the fire a funeral mass was held for the victims, and about 2,500 people crowded into the still-unfinished basement, which had been hastily roofed with boards for the occasion. So many people in such a confined, makeshift space could have posed an even greater danger in the event of a fire, but the funeral passed without incident, and most of the bodies were subsequently interred in a mass grave in the Precious Blood Cemetery, located across the river in South Hadley.

Today, despite such a substantial loss of life, the Precious Blood Church fire has been largely forgotten, and here in the South Holyoke neighborhood there are few reminders of the tragedy. The new Precious Blood Church, which was completed in 1878 and is seen on the left side of the first photo, closed in 1989, and was demolished soon after. Probably the only surviving building with a connection to the fire is the Park Street School, which still stands here in a somewhat altered state. It continued to be used as a school for many years after its use as a makeshift morgue, but around 1930 it was sold to the church, becoming a convent and chapel. At some point, the tower was removed, and the building saw other alterations such as additional windows on the second floor, but overall it is still recognizable from its original appearance, and stands as a good example of mid-19th century school architecture.