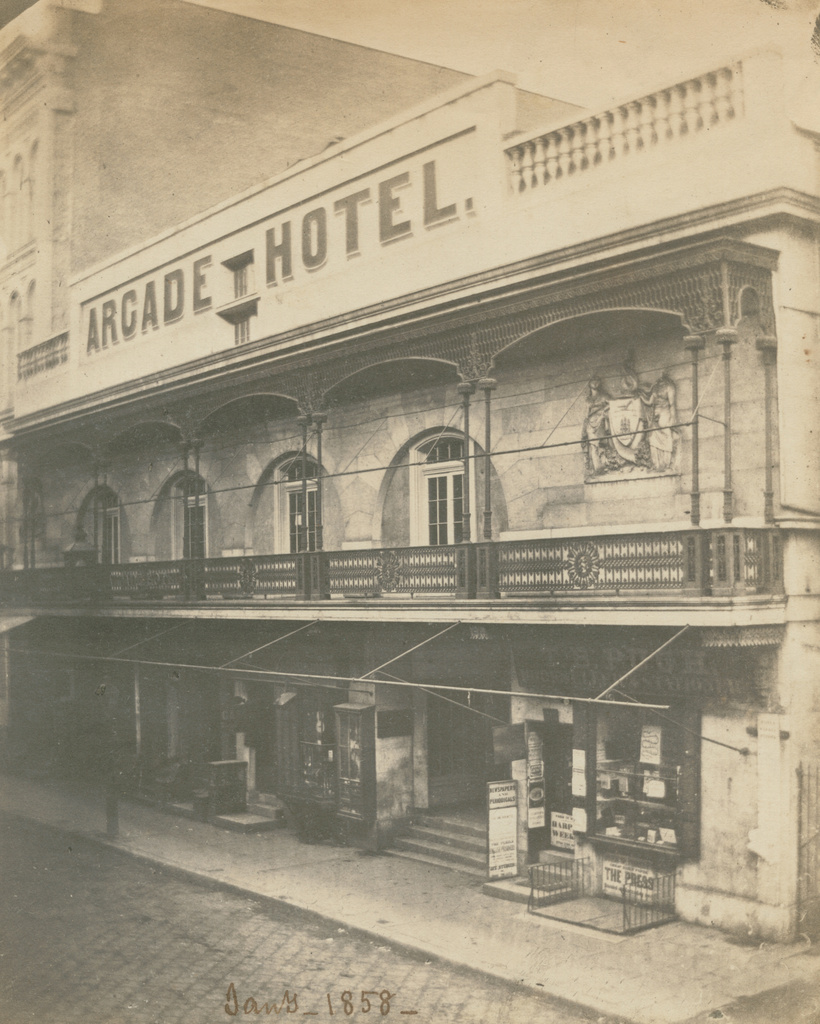

The Town Square in Plymouth, around 1865-1885. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

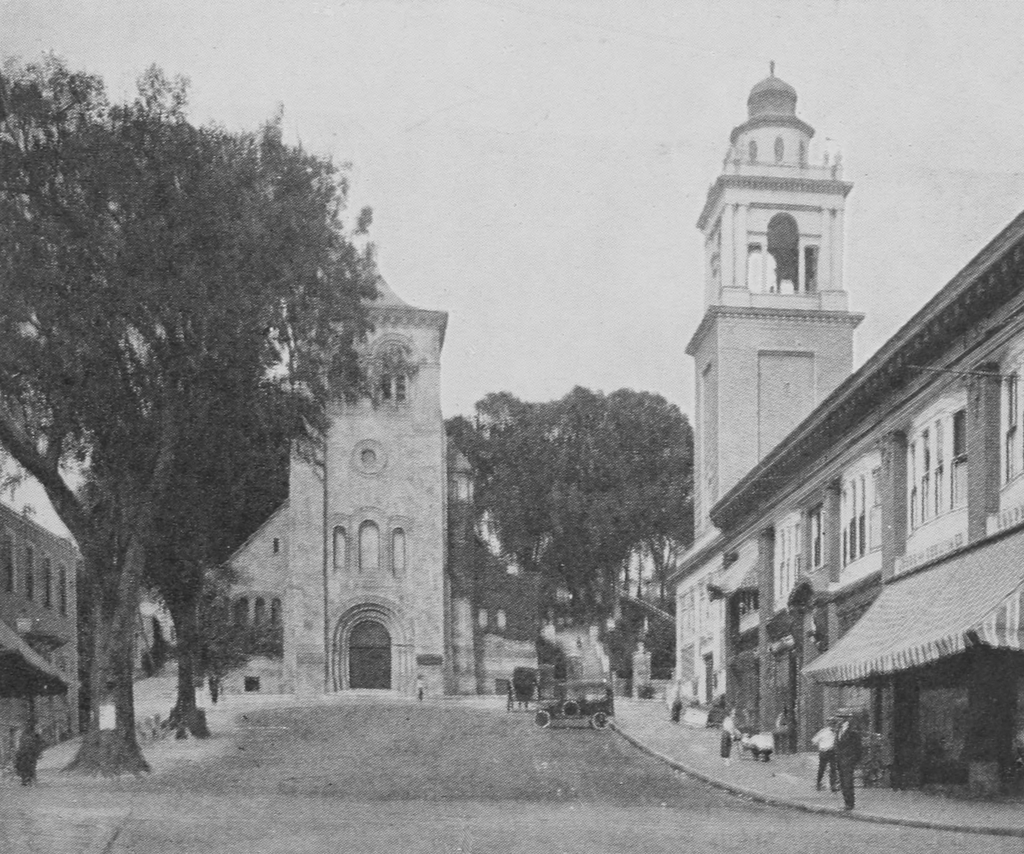

The scene around 1921. Image from Illustrated Guide to Historic Plymouth Massachusetts (1921).

The scene in 2023:

These three photos show the Town Square in Plymouth, facing west from the corner of Main and Leyden Streets. Since the early years of the Plymouth Colony, this site has been a focal point for the community, and it is surrounded by a number of historic buildings. Most significantly, the Town Square has been the site of a series of meetinghouses for the First Parish Church since the mid-1600s. However, the development around the square has also included town offices, the county courthouse, and various commercial properties over the years.

In the distance on the right side of these photos is Burial Hill. It was used as the town’s primary graveyard for much of the colonial period, but prior to that it was the location of several defensive fortifications, the first of which was built in 1621. The fort on the hill also served as the town meeting house until a purpose-build meeting house was constructed here at the square, which apparently occurred in either 1637 or 1648. It was located on the north side of the square, so it would have stood somewhere on the right side of the scene in these photos.

The 1637-48 meeting house was replaced by a second one in 1683, which stood at the west end of the square, on the site now occupied by the stone church in the center of this scene. A third meeting house was built on the site in 1744, followed by a wooden Gothic Revival church in 1831. That building is shown in the center of the top photo, and it stood here until 1892, when it was destroyed by a fire. This fire prompted the construction of the current First Parish Church of Plymouth on the same site. This Romanesque Revival church was completed in 1899, and it bears resemblance to the style of church buildings that the Mayflower Pilgrims would have known in England prior to their departure for the New World.

Although the First Parish Church was the predominant church congregation throughout the colonial period in Plymouth, other churches would eventually emerge in the town, including the Third Church of Christ in Plymouth. Established in 1801 as a result of the Unitarian-Trinitarian divide that swept through New England churches in the early 19th century, this congregation continued to follow the more conservative Trinitarian theology and practices, while the First Parish Church became Unitarian. In 1840, the Third Church of Christ built the church that stands on the right side of this scene, and that same year it became known as the Church of the Pilgrimage.

Aside from religious organizations, the Town Square was also the seat of the colony’s government for many years. At some point in the 1600s, the colony constructed a “country house” on the south side of the square, in the distance on the left side of the scene. When this was built, Plymouth was still a separate colony, so the building served as the de facto colonial capitol. It was also used as a courthouse, and this continued even after Plymouth became a part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1691. This building was eventually demolished and replaced by a new courthouse on the same site in 1749. The new building was also used for the town offices, and it still stands today. It is two stories tall and painted white, and it is visible in the distance on the left side of the bottom photo.

The area around the Town Square has also been the site of various commercial buildings over the years, particularly in the area closer to the foreground. All of the buildings in the foreground of the top photo appear to have been demolished by the time the middle photo was taken in the early 1920s, but their replacements are still standing here today. They include the Odd Fellows Block on the right, which was built in 1887, and another brick commercial building on the left, which was built around 1912.