The Willey House in Crawford Notch, probably around the 1860s or 1870s. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The scene in 2018:

The one-and-a-half-story building in the center of the first photo was built in 1793 in Crawford Notch, a long, narrow valley through the White Mountains of New Hampshire. The notch was, at the time, the only east-west route through the mountains, and this was evidently the first building to be constructed here. Known as the Notch House, it served as a tavern for travelers through here, and it was operated by several different innkeepers during the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

In the fall of 1825, the Notch House was acquired by Samuel Willey, who moved into the house with his wife Polly and their five children, who ranged in age from 2 to 11 years old. At the time, the property had been abandoned for several months, so Samuel spent much of the fall repairing the house, enlarging the stables, and making preparations for winter. The tavern was ready in time for the winter, and, despite its modest size and appearance, it was a welcome shelter for cold, weary travelers on their way through the mountains.

Willey continued to operate the tavern throughout the spring and summer of 1826, and a description of the house was published in the August 11 issue of the New Hampshire Sentinel newspaper. The writer, in describing a journey northbound through Crawford Notch, included the following account about the Notch House:

At the conclusion of this six miles, the eye is greeted with the appearance of a small but comfortable dwelling house, owned and occupied by a Mr. Willey, who has taken advantage of a small, a very small intervale, – where the bases of the two mountains seem to have paused and receded, as if afraid of coming in contact and amalgamating into one impassible pile, – to erect his lone habitation. Rude and uninviting as the spot appears, he has contrived to gather around it the necessaries if not conveniences of life. We observed a large flock of sheep in one of his inclosures; other domestic animals in the barn-yard, and several flocks of ducks and geese in the little meadow which fronted the house. We were furnished with a dinner of ham, eggs, and the usual accompaniments to such a meal in a country tavern. – The interior of the house exhibited a neatness that might well become some inns that we have seen of more frequent resort, and the faces of parents and children were the pictures of content. Can philosophy or conjecture account for or explain the motives that can induce a man thus to plant himself at a distance of six miles from the habitation of any of his race, and in a spot where it is next to impossible he can ever have a nearer neighbor?

Despite this bucolic description, though, there were more hazards to life here in Crawford Notch than simply its isolation. The house was situated at the base of a steep slope, on a narrow plot of flat ground between the mountain in the back, and the Saco River in front of the house on the other side of the road. As a result, this location was vulnerable to landslides, and its occupants would have no viable way to escape its path if one was to occur.

This reality became very clear to the Willey family in June 1826, when they survived a close call from one such landslide. The slide, which came within less than 200 feet of their house, covered about an acre of land by Samuel’s estimate, and it traveled nearly a mile in a matter of minutes. An account of this event was published in the New England Galaxy, and it subsequently appeared in The Farmers’ Cabinet on August 12, 1826, in an article that included the following description:

Just before our visit to this place, – on the 26th of June, – there was a tremendous avalanche, or slide, as it is there called, from the mountain which makes the southern wall of the passage. an immense mass of earth and rock from the side of the mountain was loosened from its resting place and began to slide towards the bottom. In its course it divided into three portions, each coming down with amazing velocity into the road, and sweeping before it shrubs, trees and rocks, and filling up the road beyond all possibility of its being recovered.

The article went on the describe the Willey family’s reaction:

The place from which this slide or slip, was loosened, is directly in the rear of Mr. Willey’s house; and were there not a special Providence in the fall of a sparrow, and had not the fingers of that Providence traced the direction of the sliding mass, neither he nor any soul of his family would ever have told the tale. – They heard the noise when it first began to move, and ran to the door. In terror and amazement, they beheld the mountain in motion. But what can human power effect in such an emergency? Before they could think of retreating, or ascertain which way to escape, the danger was past.

According to Samuel’s brother Benjamin, who discussed the event in a book many years later, the Willeys had initially planned on moving away after this near-disaster, but upon further reflection they decided to stay. Benjamin related a conversation that Samuel had with another person after the incident, with Samuel supposedly explaining, “Such an event, we know, has not happened here for a very long time past, and another of the kind is not likely to occur for an equally long time to come. Taking things past in this view, then, I am not afraid.”

Over the next two months, the region experienced a severe drought that dried the soil to a much greater depth than usual. However, this drought came to a sudden end on the night of August 28, when a severe storm passed through here. The torrential rainfall destroyed nearly all of the bridges in the notch, and it also soaked deep into the dry earth, making the ground particularly susceptible to landslides along the steep cliffs. One such slide occurred here at the Notch House, but, as in the June slide, the building was narrowly spared. It stood right in the path of the landslide, but the falling debris struck a low ridge just above the house, causing it to split into two streams. As a result, the landslide passed on both sides of the house, destroying the stables but otherwise leaving the building miraculously intact before reuniting into a single stream just below the house.

Over the next few days, though, the nearby residents of the notch could find no sign of the seven members of the Willey family, or the two hired men who lived here. Inside the house, there was evidence that the occupants had left in a hurry, suggesting that they had tried to flee to safety in advance of the landslide. Subsequent searches of the area uncovered the badly-mangled bodies of Polly Willey and one of the hired men, David Allen, in the debris below the house. Samuel’s remains were soon discovered as well, along with those of their youngest child, three-year-old Sally. The body of David Nicholson, the other hired man, was found five days after the disaster, and a day later the body of twelve-year-old Eliza Willey was found far from the house, on the other side of the Saco River. However, the other three children—eleven-year-old Jeremiah, nine-year-old Martha, and seven-year-old Elbridge—were never found.

In the aftermath of the disaster, there were many theories as to exactly what happened here on the night of August 28. The most likely explanation, which Benjamin Willey provided in his book, is that Samuel stayed up during the night to monitor the storm and watch for signs of a landslide. As he heard the slide approaching, he awakened his family, and as they were leaving they heard the sound of the stables being destroyed. This caused them to flee in the opposite direction, and in the darkness and pouring rain they unknowingly ran directly into the path of the other side of the landslide.

Regardless of the actual sequence of events, though, the news of the disaster quickly spread across the country. Within just a few months, curious sightseers were making their way up to Crawford Notch to see the house and the devastation caused by the landslide, and over the next few years many more continued to arrive. This helped to fuel a nascent tourist industry here in the White Mountains. At the time, the eastern United States was becoming increasingly industrial and urbanized, and many were drawn by the primeval wilderness of the area and the destructive forces of nature that were demonstrated in the Willey disaster. Local innkeeper Ethan Allen Crawford—for whose family the notch is named—enjoyed brisk business in the aftermath of the tragedy, and in 1828 he constructed a new hotel a few miles away from here at the gates of the notch. Even Samuel’s brother, Benjamin Willey, capitalized on the influx of tourism by charging visitors for a guided tour of the house.

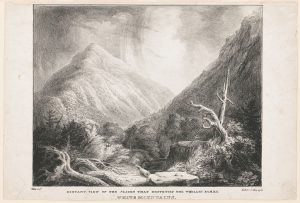

The tragedy also inspired noted artists and writers. Painter Thomas Cole visited here in October 1828, and he described how “[t]he sight of the Willey House, with its little patch of green in the gloomy desolation, very naturally recalled to mind the horrors of the night when the whole family perished beneath an avalanche of ricks and earth.” Cole was the founder of the Hudson River School art movement, and his paintings typically featured dramatic landscapes that emphasized both the beauty and the dangers of the untamed American wilderness. This setting in Crawford Notch, combined with the Willey disaster, was perfect subject matter for Cole, and he subsequently painted this scene. The painting, titled Distant View of the Slides that Destroyed the Whilley [sic] Family, is now lost, but there are several surviving lithographic reproductions, including the one below, which is located at the Library of Congress.

In addition to Cole, author Nathaniel Hawthorne also incorporated the disaster into one of his works. In 1835, when he was still a young, relatively obscure author, he published the short story “The Ambitious Guest,” which was based on the event. The story does not mention the Willey family by name, and there are some differences in the ages and composition of the family, but otherwise it is largely a retelling of the commonly-accepted theory about the Willey family’s demise. However, Hawthorne embellishes it by adding a character—the eponymous ambitious guest—who arrived at the house on the night of the storm. In the story, the young man talks with the family about his desire to leave a legacy so that he will be remembered after death. In the end, though, he dies along with the rest of the family, his body is never found, and there is uncertainty among the locals as to whether or not there had even been a guest in the house at the time.

In the meantime, the Willey House continued to be a popular attraction. By the mid-19th century, the White Mountains had become a major tourist destination, thanks in large part to the publicity surrounding the Willey disaster. A number of new hotels were constructed around this time, including one right here at the Willey House. In 1845, local hotelier Horace Fabyan purchased the property and constructed a new hotel directly adjacent to the old house, as shown on the left side of the first photo. It was named the Willey Hotel, and it stood three stories in height and measured 40 feet by 70 feet, with a capacity of 50 people.

The hotel and house were still standing here when the first photo was taken around the 1860s or 1870s. By this point, some 40 to 50 years after the disaster, there was little visual evidence of the destructive landslide, but the house remained an important local landmark. It survived for several more decades, but ultimately met the same fate as so many other White Mountain hotels when it was destroyed by a fire in September 1899, evidently as a result of a defective chimney.

Today, more than 120 years after the fire, the house is long gone, but the story remains an important part of local lore. The site of the house is now marked by a small stone monument in the center of the first photo, and immediately to the left of it is a visitor center and the park headquarters of the Crawford Notch State Park. Further in the distance, the only landmark left from the first photo is the mountain itself, which looms more than 2,000 feet above the floor of the valley. At 4,285 feet in elevation, it is the 29th-tallest mountain in the state, and it is, appropriately enough, named Mount Willey.