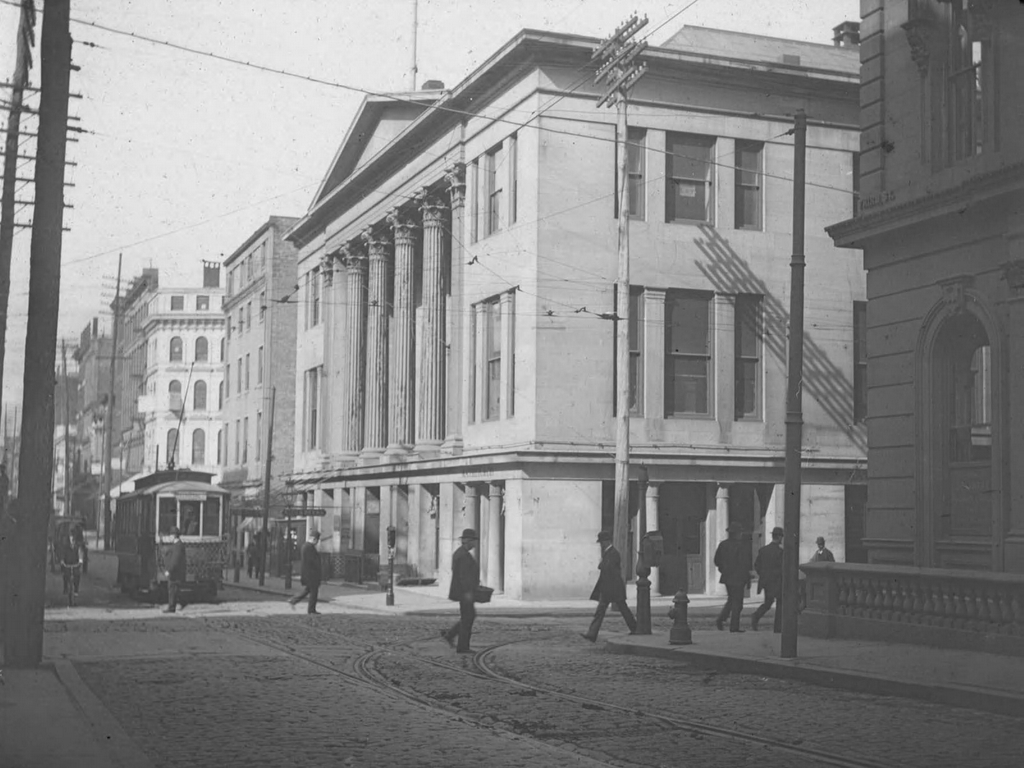

The Merchants’ Exchange Building, seen from the corner of Walnut and South Third Streets in Philadelphia in 1898. Image courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia, John C. Bullock Lantern Slide Collection.

The scene in 2019:

The Merchants’ Exchange Building is an important architectural landmark in Philadelphia, and it is also significant for having been the financial center of the city for many years. It was completed in 1834 as the first permanent home of what would become the Philadelphia Stock Exchange. Prior to this time, brokers and merchants met in a variety of coffee houses and taverns. However, by 1831 the city’s business leaders had recognized the need for a permanent, central location for a stock exchange, and began planning such a building.

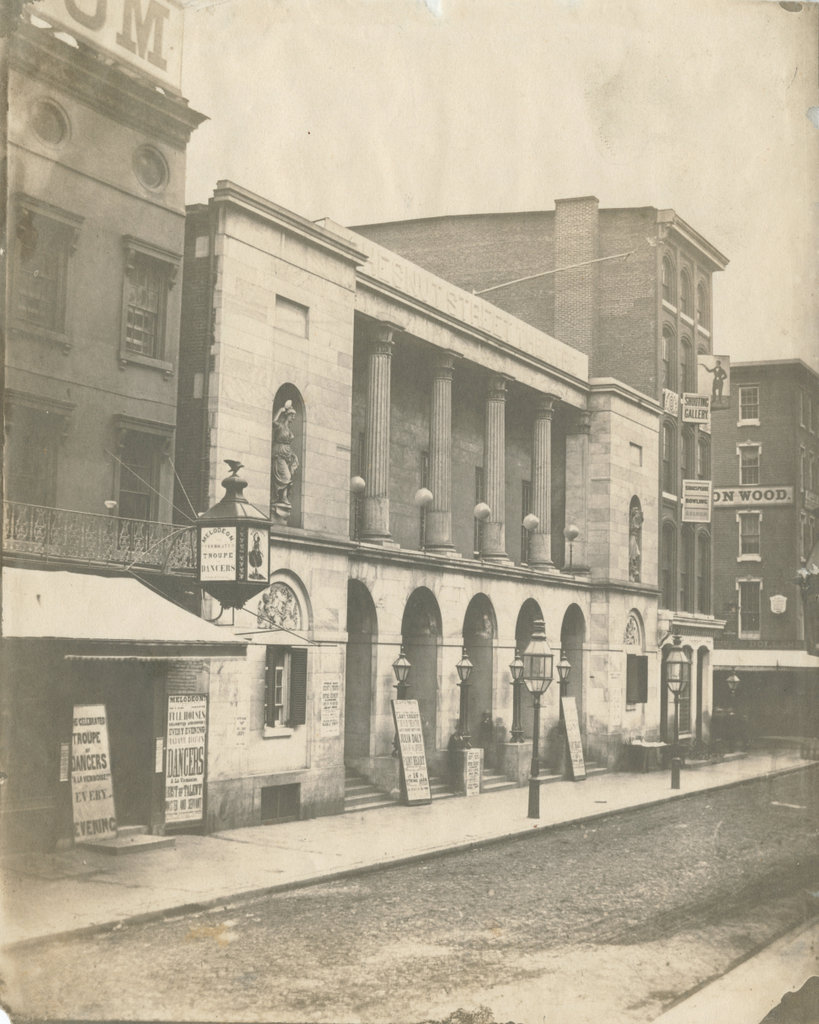

The Exchange was designed by prominent Philadelphia architect William Strickland, who was heavily inspired by classical Greek architecture. The shape of the lot also contributed to the building’s design; although most of Philadelphia features a rectangular street grid, the Exchange was built on a triangular lot that was created by the diagonally-running Dock Street. As a result, the two main facades of the building are very different. Here at the west end of the building on Third Street, it has a fairly standard Greek Revival exterior, with Corinthian columns supporting a triangular pediment. However, on the east side of the building, facing Dock Street, Strickland designed an elaborate semi-circular columned facade that was topped by a tower. This tower, which is partially visible in the upper right corner of the 2019 photo, was inspired by the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates in Athens, which dates back to the fourth century B. C.

The cornerstone of the building was laid on February 22, 1832, on the one hundredth anniversary of George Washington’s birth. It was completed two years later, opening to the public in March 1834. A contemporary article in the Philadelphia Inquirer, republished from Bicknell’s Reporter, provides the following description:

It is built entirely of marble— occupies ninety-five feet front on Third street, and one hundred and fifty feet on Walnut. The basement story is fifteen feet high, and has twelve doorways on the Third Street front and flanks. The largest room in the lower floor, which is 74 by 36 feet, is occupied as the Philadelphia Post Office, at the west end of which is a hall or passage, designed for the shelter of persons while receiving or delivering letters. Beyond this hall to the west, and fronting Third street, is a large and commodious room, which has been fitted up as a Coffee Room, is now in the occupancy of Mr. J. Kerrison, a gentleman every way qualified to conduct a respectable establishment of the kind. South of the Post Office and the Coffee Room, is a large passage which runs from Dock to Third street, and further south again, a number of offices; which are to be occupied generally as Exchange and Insurance Offices. They open upon Walnut and Dock streets. No. 2 of this range will be occupied by the proprietor of this paper, as a Stock, Exchange and Publication Office.

Proceeding up stairs, the large Exchange Room, capable of containing several thousand persons, first arrests attention. It occupies an area of 83 superficial feet, fronts east, and extends across the whole building. The reading Room is oa [sic] the second floor, immediately over the Post Office, and is nearly of equal capacity. It is fitted up in the most appropriate manner, and is under the charge of Joseph M. Sanderson, Esq. assisted by Mr. J. Coffee. Both gentlemen are well know to our citizens, and are alike respected for urbanity of manner, intelligence, and attention to the duties entrusted to their care. Both have for several years been connected with the Merchants’ Coffee House of this city, Mr. Sanderson as Principal and Lessee of that establishment, and nothing can more fully show the estimation in which he is held by the Merchants than the fact of his unanimous election to the New Exchange.

The attic story is of the same height as the basement, 15 feet, contains six large rooms; the roof is of copper, and the ornaments on the semicircular portion over the front colonnade are very beautiful.

The building went on to serve as the city’s stock exchange for more than 40 years, in addition to housing other tenants such as the post office. However, in 1876 the stock exchange moved to the Girard Bank, located less than a hundred yards north of the Merchants’ Exchange on the opposite side of Third Street. This building was the home of the stock exchange until 1888, when it relocated to the Drexel Building a few blocks away. In a somewhat surprising move, though, the stock exchange then returned here to the Merchants’ Exchange at the turn of the 20th century, shortly after the first photo was taken. It remained here until 1913, when it moved into a new building at 1411 Walnut Street, near the corner of Market Street.

The Merchants’ Exchange Building was ultimately acquired by the National Park Service as part of the Independence National Historical Park. Although many other historic buildings within the park’s boundaries were demolished during this time, this building was preserved and restored, and it is now used as the park headquarters. It stands as the only surviving building in this scene from the first photo, and in 2001 it was designated as a National Historic Landmark because of its historical and architectural significance.