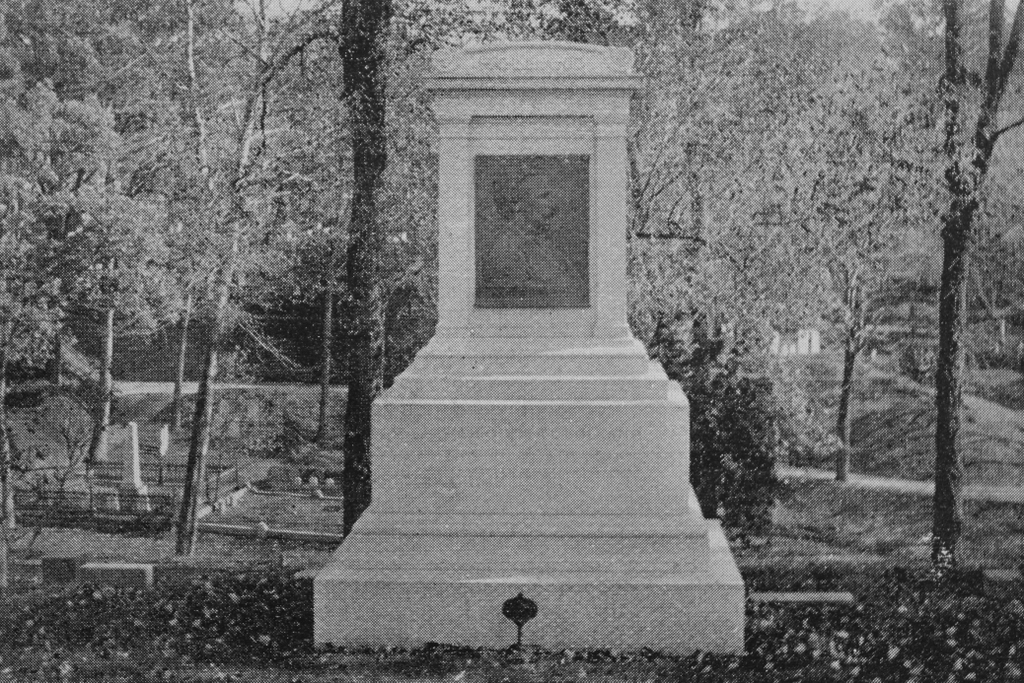

A scene in Springfield Cemetery, facing the southern section of the cemetery, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

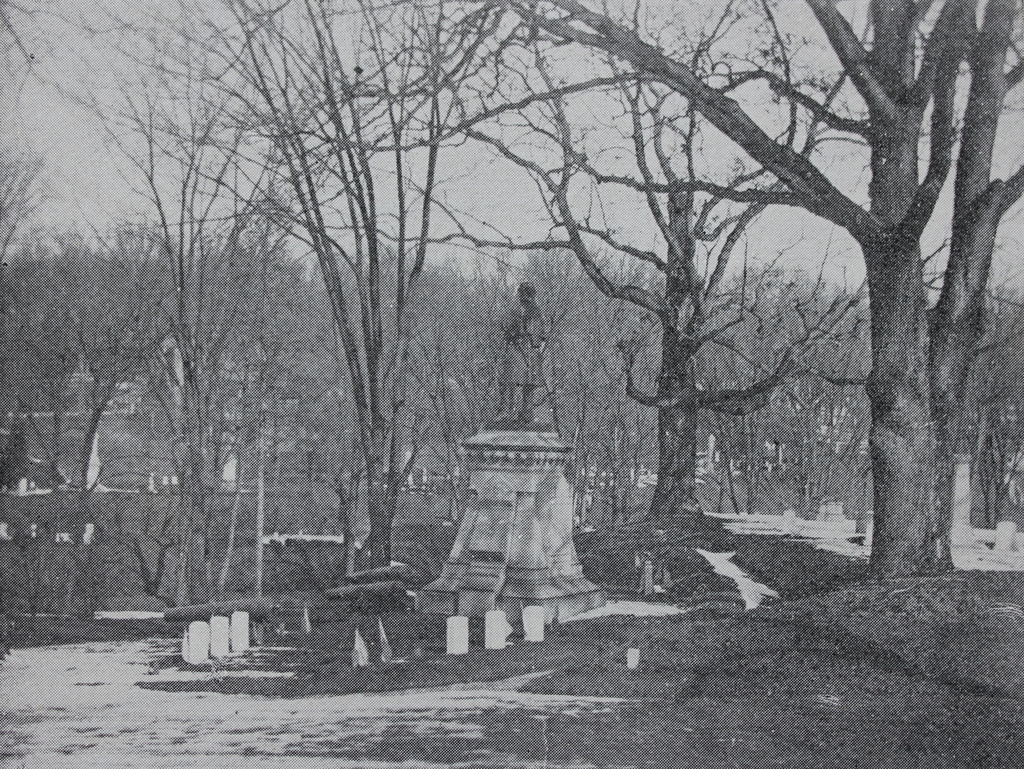

The scene in 2020:

Springfield Cemetery was established in 1841, and it was part of a trend that involved creating well-landscaped, park-like cemeteries on the outskirts of cities and towns, as opposed to the older, often gloomier Puritan-era graveyards in town centers. The first of these cemeteries was Mount Auburn Cemetery in the suburbs of Boston, which opened in 1831, and many other cities soon followed, including Springfield a decade later. Over the years, it would become the final resting place for many of the city’s prominent 19th century residents, and it remains an active cemetery today.

The cemetery is located in a ravine that was originally known as Martha’s Dingle. In transforming the area into a cemetery, the designers incorporated the natural features into the landscape by creating a series of terraces that were separated by wooded slopes. These were linked together by curving paths that followed the contours of the land. Overall, the intent was to create a place that would serve not only as a burial ground for the dead, but also as a quiet, peaceful place for the living to visit.

The view here in these two photos shows the upper section of the cemetery, facing south in the direction of Cedar Street. In the distance is the southernmost section of the cemetery, which, unlike the rest of the cemetery, lacks the winding paths and landscaped terraces. Instead, the lots here are laid out on flat ground, with few trees and with straight paths that intersect at right angles in a grid pattern. Most of the gravestones in that section date to the second half of the 19th century, and by the time the first photo was taken in the early 1890s it was already crowded with towering obelisks and other monuments.

By contrast, the slightly lower area here in the foreground was nearly devoid of gravestones when the first photo was taken. Of the two that are present near the foreground, the one in the lower center of the scene has apparently been removed or replaced, but the other one, further to the left, is still there. It features a veiled figure with an urn standing atop an Ionic column, marking the grave of James Abbe, who died in 1889 at the age of 66. He was a stove and tin merchant, and he was also a director for several local corporations, including serving as president of the Hampden Watch Company. In addition, he was a state legislator from 1876-1877, and he served as a trustee for the Springfield Cemetery Association.

Today, more than 125 years after the first photo was taken, Abbe’s gravestone is still here, although it is now mostly hidden by a tree from this angle. Otherwise, the most significant difference here is the number of gravestones in the foreground. This section was mostly empty in the early 1890s, but it now features a number of 20th century gravestones. Perhaps the most prominent person buried in this section is Horace A. Moses, a paper manufacturer and philanthropist who was one of the founders of Junior Achievement. He died in 1947, and his gravestone is the bench-like monument on the far left side of the scene.

Overall, despite the increase in gravestones, this section of Springfield Cemetery has not changed much since the late 19th century. The level upper section in the distance is mostly hidden behind trees from here, but it still looks largely the same as it did in the first photo, with rows of large monuments. By contrast, even though it has more gravestones now than in the first photo, the area in the foreground still has much more of a rural, park-like appearance, with its winding roads and mature shade trees, as shown in the present-day scene.