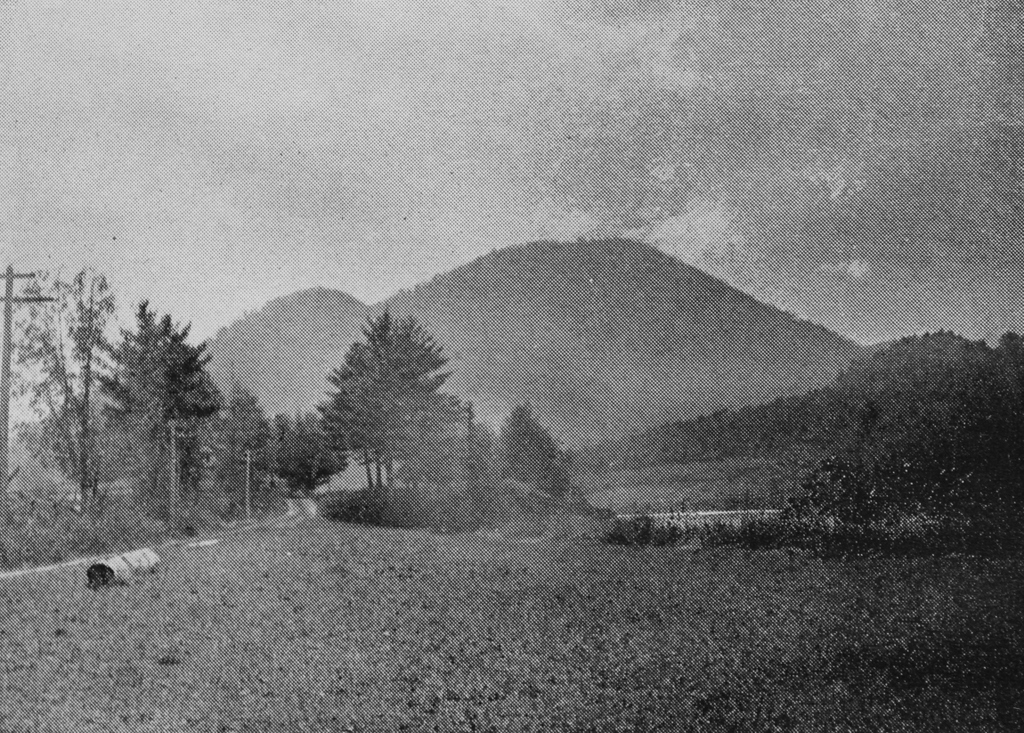

The view looking east along the Deerfield River in the western part of Charlemont, around 1891. Image from Picturesque Franklin (1891).

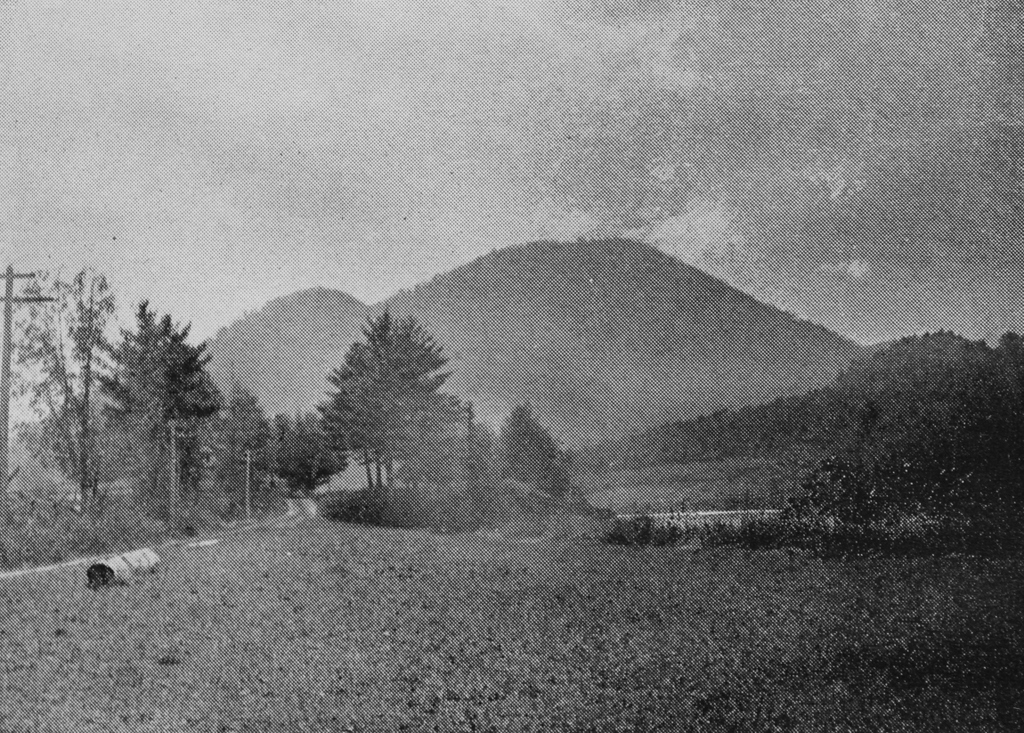

The scene in 2021:

These two photos show the road heading toward the center of Charlemont, with the Deerfield River on the right and the distinctive summits of Mount Peak in the distance. Today, the road is known as the Mohawk Trail, and its route through the Berkshires offers some of the finest scenery in the state. However, the current road is largely an early 20th century creation, and its route over the mountains bears little resemblance to its predecessors.

The northern Berkshires have long been a major obstacle to east-west travel through the area. Unlike further south, there are no low-elevation mountain passes here. For a westbound traveler, heading in the opposite direction of where these photos are facing, the Deerfield River valley provides an easy route deep into the mountains. However, a few miles to the west of here, the narrow valley turns abruptly to the north at the base of the Hoosac Mountains. These mountains form a continual ridgeline for miles in either direction, with elevations exceeding two thousand feet.

In the pre-colonial period, Native Americans crossed the mountains by way of a footpath, but not until the 1750s did European settlers build a road across the mountain. This road was later improved and partially rerouted in the 1760s, and it appears to have followed the Deerfield River before ascending along the northern slope of Clark Mountain. Then, in 1797, the Second Massachusetts Turnpike was incorporated to construct a toll road across the mountains. Rather than beginning the ascent at Clark Mountain, this road followed the river along present-day Zoar Road and River Road almost as far as the current site of the Hoosac Tunnel, before climbing up the mountain by way of Whitcomb Hill Road. However, many travelers chose to continue taking the older road in order to avoid paying tolls on the new turnpike, so the older road came to be known as a “shunpike.”

This information is relevant to this particular site here in Charlemont, because the rest area on the right side of the present-day photo is known as the Shunpike Rest Area. It features a historical marker, installed by the Mohawk and Taconic Trail Association in 1957, that reads:

To the Thrifty Travelers of the Mohawk Trail who in 1797 here forded the Deerfield River rather than pay toll at the Turnpike Bridge and who in 1810 won the battle for free travel on all Massachusetts Roads.

However, despite the claims of this sign, there seems to be little historical evidence to suggest that this spot in Charlemont was where shunpike travelers would ford the river. The turnpike bridge over the Deerfield River was some 3.5 miles further upstream from here, at the border of Charlemont and Florida. That bridge was also the eastern end of the turnpike; the company’s original charter allowed it to construct a turnpike over the mountain “from the west line of Charlemont.” In addition, that bridge was the point where the turnpike and the older road diverged, so it seems more likely that these “shunpikers” would have crossed the river somewhere near that bridge, rather than several miles downstream at this spot.

In any case, the first photo was taken sometime around the early 1890s, only a few decades before the road through the mountains was substantially upgraded with the construction of the Mohawk Trail. Heading west through Charlemont, it follows existing roads as far as this spot here, but just to the west of here, in the opposite direction of these photos, the Mohawk Trail crosses to south side of the Deerfield River. It then follows the steep, narrow gorge of the Cold River, a smaller tributary of the Deerfield, before making its final ascent to the plateau at the top of the ridgeline.

With its current route, the Mohawk Trail completely bypasses the earlier roads up the eastern side of the mountain, including both the turnpike and the earlier shunpike. It also does not go anywhere near the part of the Deerfield River where turn-of-the-19th-century shunpikers would have most likely forded the river. If that is the case, it raises the question of why this historically-dubious marker would have been placed here at this rest area.

The answer might have something to do with the date that this historical marker was installed here. The modern-day Massachusetts Turnpike, which bears no relationship to similarly-named roads of the 19th century, opened in 1957, the same year that this marker was installed. According to newspaper articles from the period, local residents along the Mohawk Trail were concerned that the new highway would hurt business here in the northern part of the state. So, the Mohawk and Taconic Trail Association created the slogan “Go turnpike—return shunpike” in the hopes of encouraging motorists to make a grand tour of western Massachusetts, rather than taking the turnpike in both directions.

Probably not coincidentally, this was the same association that, around the same time, dedicated this historical marker “To the Thrifty Travelers.” It would not have been possible to place such a marker on the Mohawk Trail at the seemingly more plausible site of the shunpike ford, since the road does not go there. Instead, the road’s promoters seem to have played fast and loose with the history in order to appeal to nostalgia and Yankee frugality, in order to boost tourism through here.

Regardless of the accuracy of the historical marker, though, this particular section of the Mohawk Trail has been part of the east-west route through the northern Berkshires since at least the 18th century, with maps as early as the 1790s showing it taking this same course eastward toward Charlemont. The road is very different from its appearance in the first photo, and the rest area now takes the place of the meadow next to the river, but the road is still in the same spot, and this scene is still easily recognizable from the first photo because of Mount Peak in the distance.