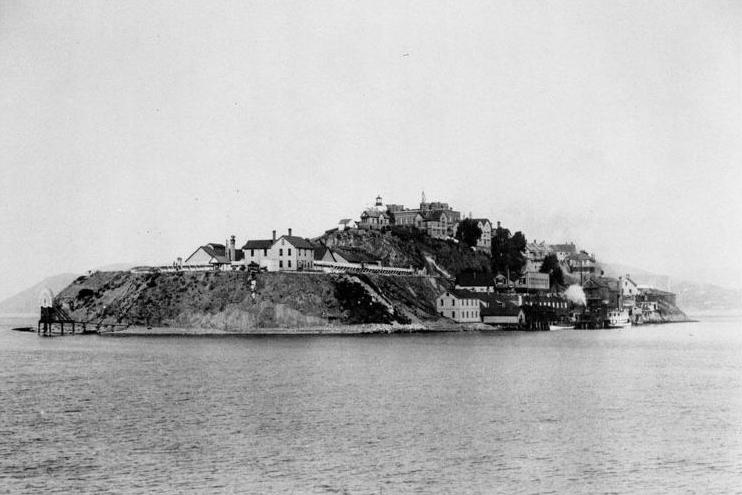

Alcatraz Island in San Francisco Bay, around 1902-1905. Image courtesy of the National Park Service.

Alcatraz in 2015:

Alcatraz Island is located at a strategic point just inside the entrance to San Francisco Bay. The United States acquired California in 1848, and within ten years this small island had been fortified to protect the bay from any potential threats. Known as the Alcatraz Citadel, it was finished just in time for the Civil War, and although it never saw any combat during the war, its isolated location made it an ideal place to house Confederate prisoners.

After the war, the focus on Alcatraz shifted from defense to incarceration, and from 1868 to 1933 it functioned as a military prison. The first photo was taken during this era, showing a number of buildings on the island that were used to house either the inmates or the military personnel stationed there. At the top of the hill in the first photo is the Alcatraz Citadel, which was demolished a few years later to build the main prison building that stands there today. Most of the other buildings from the first photo have since been demolished, including those along the water, which were replaced by Building 64 in 1905. This large building, which was originally used to house military officers and their families, is still standing today just to the right of the center of the photo.

When the military prison closed in 1933, the property was transferred to the Department of Justice, and in 1934 it reopened as a civilian prison for the nation’s most difficult prisoners. Considered essentially escape-proof, there were never any confirmed successful escapes, although three inmates did disappear in the famous 1962 attempt. Alcatraz was expensive to maintain, though, and it closed in 1963. After the closure, the island was occupied by Native Americans for 19 months in 1969-1971, during which time several of the buildings were burned. Later, the island was acquired by the National Park Service, and is now open to the public as part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

This post is part of a series of photos that I took in California this past winter. Click here to see the other posts in the “Lost New England Goes West” series.