The Stone House on the Warrenton Turnpike (present-day US Route 29) just north of Manassas, Virginia, in March 1862. Image taken by George N. Barnard, courtesy of the Library of Congress, Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints collection.

The house in 2021:

These two photos show the Stone House, which is located on the Warrenton Turnpike just to the north of Manassas, Virginia. This house is a famous Civil War landmark because of its role in the First Battle of Bull Run in 1861, and also in the Second Battle of Bull Run a year later. Despite being in the midst of the fighting during both battles, the house survived the war, and it has been preserved in its Civil War-era appearance.

The exact date of construction is uncertain, but the evidence seems to suggest that it was built around 1848. Two years later, the house was sold to Henry P. Matthews, along with 137 acres of land. He and his wife Jane were living here ten years later, with the 1860 census listing Henry as a farmer. His property was valued at $1,600, and he also had a personal estate of $600. His farm included a variety of livestock, such as horses, cattle, sheep, and pigs, and he primarily produced rye, corn, oats, and hay. Henry’s name does not appear in the slave schedules for that year’s census, although Jane was listed as enslaving a 10-year-old boy.

Just a year later, the Matthews family’s quiet farming lifestyle was disrupted by the outbreak of war. The Civil War had begun with the capture of Fort Sumter in April 1861, but the next few months were relatively uneventful, with each side gathering forces and preparing for war. For the Union, one of its major goals was capturing the Confederate capital of Richmond, located just a hundred miles south of Washington, DC. To that end, on July 16, 1861, General Irvin McDowell marched about 35,000 soldiers south from Washington to Manassas, Virginia, where General P. G. T. Beauregard was encamped with a large force of Confederate soldiers.

The ensuing battle occurred on July 21, and it was generally termed the First Battle of Bull Run by northerners, and the First Battle of Manassas by southerners. This was the first major battle of the war, and it gave a preview of things to come. Going into the battle, the Union had been confident of victory. But, by the end of the day it was apparent that this war would be much longer and bloodier than either side had anticipated.

Ahead of the battle, Confederate forces had taken a defensive position on the south side of Bull Run, a small river near Manassas. McDowell’s Union forces attempted to outflank the Confederates by crossing Bull Run to the north of the Stone House. The Confederates countered this move by occupying Buck Hill, the small hill in the distance of this scene behind the house. The Union then occupied Matthews Hill, located a little further to the north beyond Buck Hill. Confederates attacked this Union position, but they were ultimately unsuccessful, and the Union drove them southward off Buck Hill, past the Stone House, and onto Henry Hill, located about a half mile to the south of the Stone House.

Henry Hill was the site of the most intense fighting of the battle, and it was there that Confederate General Thomas Jackson earned the moniker “Stonewall Jackson.” During this stage of the battle, the Stone House was behind the Union lines, so it soon became a makeshift hospital, with its stone walls affording some measure of protection from the ongoing fight. Many wounded Union soldiers made their way here or were brought here, but over the course of the afternoon the Union lines began to crumble, eventually forcing a retreat. Unable to retreat, many of the wounded men were still here when the Confederates regained the Stone House, and they were subsequently taken prisoner.

In the meantime, the Union retreat had become a disorganized rout, as soldiers fled in the direction of Washington. It was a disastrous start to the war for the Union, which was increasingly realizing the enormity of the task at hand. The next day, Abraham Lincoln signed a bill to enlist a half million soldiers for the next three years, and on July 25 General McDowell was relieved of his command as a result of the debacle.

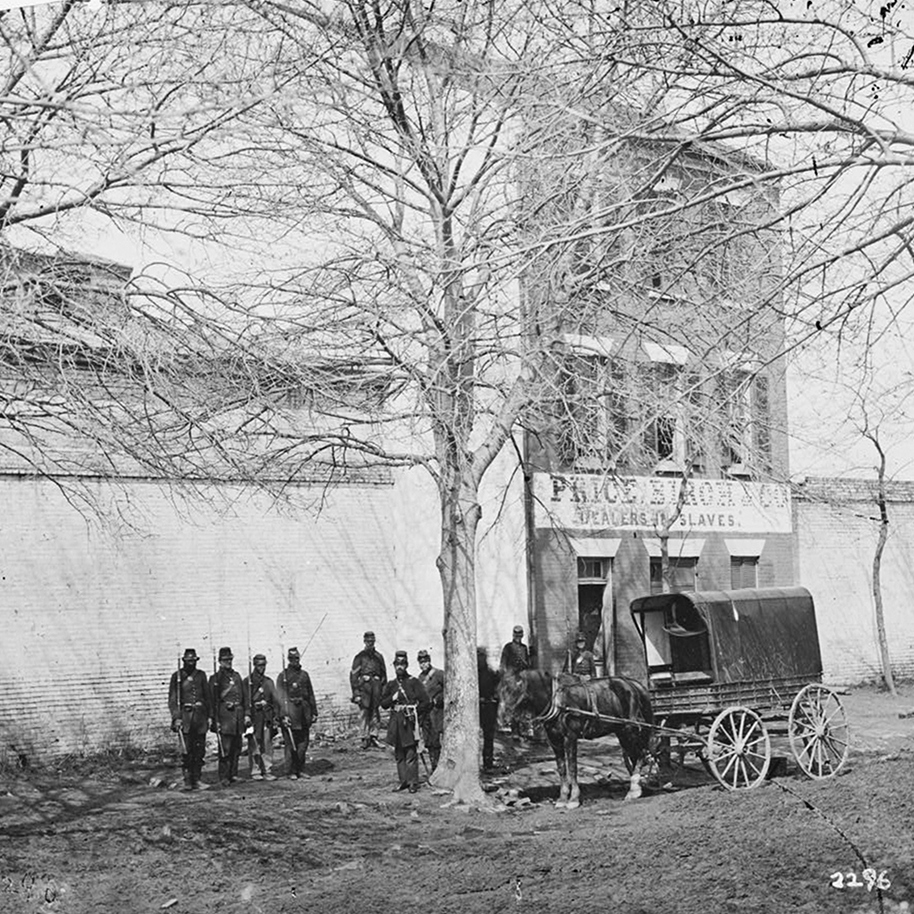

The Confederates would occupy the Manassas area until March 1862, when they withdrew south to defend Richmond from the anticipated Peninsular Campaign. The first photo was taken around this time, showing some of the battle damage from the previous summer. Many of the window panes were still broke, while other windows were boarded up, and there appears to have been some damage to the masonry walls, particularly in the area to the right of the front door.

As it turned out, this would not be the last time that the Stone House would see combat. General George McClellan’s attempt to take Richmond from the east had stalled by the summer, so the Union sent General John Pope into northern Virginia. Knowing that McClellan was no longer a serious threat to Richmond, Confederate General Robert E. Lee moved some of his forces north in order to counter Pope’s advance.

The two armies ultimately clashed here in the vicinity of Manassas, just to the north of where the original battle had been fought. As had been the case during the first battle, the Stone House was in the rear of the Union lines for much of the Second Battle of Bull Run, so it again served as a hospital for wounded Union soldiers. The battle was fought over the course of three days, from August 28 to 30, 1862. But, just like a year earlier, the battle ended in defeat for the Union army, which was again plagued by poor leadership.

In another repeat of the previous year, the wounded soldiers here at the Stone House were captured by the Confederates, although they were paroled rather than being held as prisoners. Part of the reason for this was because, in the wake of his victory, Lee had greater ambitions. Following his success here, he north into Union territory, and just over two weeks later he fought Union forces in Maryland at the Battle of Antietam, on September 17, 1862. In that battle, however, Lee’s advance was halted. He was forced to return south into Virginia, and Lincoln used the victory as an opportunity to issue the Emancipation Proclamation.

There was no further combat here at the Stone House for the remainder of the war, and at some point the battle damage was repaired. However, Henry and Jane Matthews did not remain here for much longer, as they sold the house in 1865, shortly after the end of the war. The house would change ownership a few more times during the late 19th century. Mary Starbuck owned it from 1865 to 1879, followed by George Starbuck until 1881 and then Benson Pridmore until 1902. The next owner was Henry J. Ayers, and the house was owned by his family for nearly 50 years before it was acquired by the National Park Service in 1949.

With this change in ownership, the house and 80 acres of land became part of the Manassas National Battlefield Park, which had been established in 1936. During the 1950s, the house was used as a residence for park employees, but in the early 1960s it was restored to its Civil War appearance. It has remained this way ever since, standing as an important landmark from the two major battles that had been fought here.