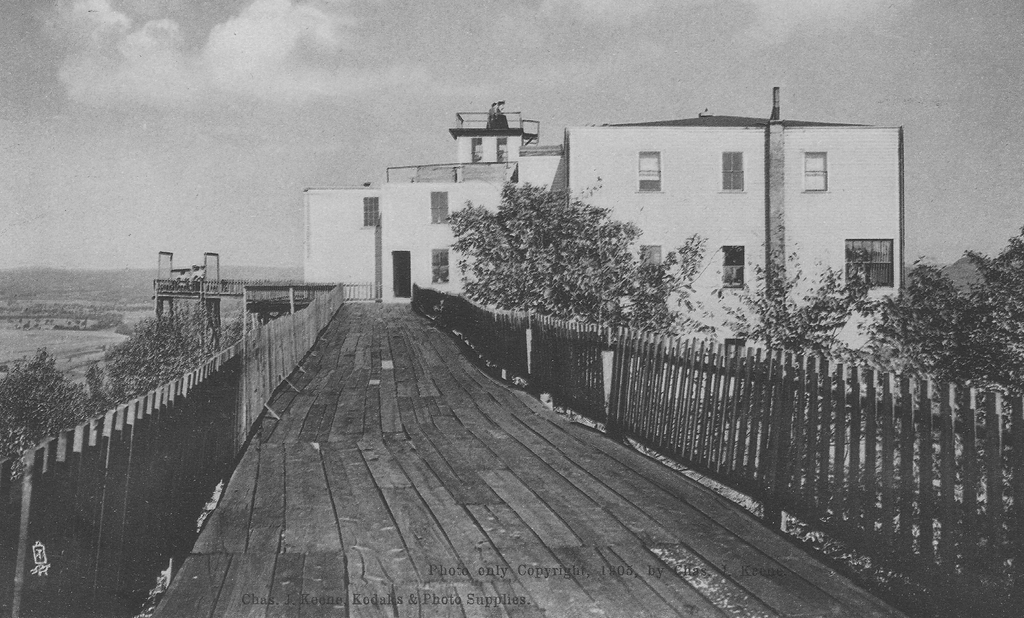

The trolley Rowland Thomas on the Mount Tom Railroad in Holyoke, around 1905-1915. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2021:

The early 20th century was the heyday of electric trolleys in the United States. In the years prior to widespread car ownership, most cities and even many small towns were served by networks of trolley lines that were generally run by private companies. In order to maximize profits, these companies often built picnic groves, amusement parks, and other recreational facilities along their lines. Known as trolley parks, these generated revenue not only through admission fees, but also through increased trolley ridership on otherwise-slow weekends.

Here in Holyoke, the Holyoke Street Railway Company opened Mountain Park in the 1890s. It began as a small park at the base of Mount Tom, but it soon added amenities such as a dance hall, a restaurant, a roller coaster, and a carousel. Most significantly, though, the company also built a summit house at the top of the 1,200-foot mountain, allowing visitors to enjoy the expansive views of the Connecticut River valley. Mountaintop resorts were popular in the northeast during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and there were already several in the vicinity of Mount Tom, including the Prospect House on Mount Holyoke and the Eyrie House on Mount Nonotuck. However, unlike those establishments, the Summit House here on Mount Tom was not a hotel. Instead, it catered to day visitors, with a restaurant, a stage, and an observatory equipped with telescopes.

To bring visitors to the Summit House, the company constructed the Mount Tom Railroad, a nearly mile-long funicular railway that rose 700 feet in elevation from Mountain Park to a station just below the summit. It had an average grade of 14 percent, with a maximum grade of 21.5 percent at its steepest section. The lower part of the route was straight, as shown here in this view looking down from the midpoint, although there was a gentle curve right before the summit station. Like most funiculars, it consisted of two cars that were connected by a cable. As one car descended, it pulled the other car up the mountain, allowing gravity to do most of the work. The cable itself was unpowered, but the cars each had their own electric motors powered by overhead wires, in order to compensate for weight differences and energy lost to friction.

The two cars were named the Rowland Thomas and Elizur Holyoke, in honor of the early colonists who became the namesakes of Mount Tom and Mount Holyoke. Each car was 36 feet long, 9 feet wide, and could seat 84 passengers. They were connected to each other by a 5,050-foot-long, 1.25-inch steel cable, which passed over a large sheave at the summit. This sheave was mounted on an A-frame that was, in turn, bolted securely into the rock. In addition, the cars maintained constant telephone connection with each other, by way of telephone lines that ran alongside the tracks just above ground level, as shown in the lower left corner of the first photo. The cars connected to these by way of brush-like shoes that ran along the top of the wires as the car moved.

Because of the steep grade of the railroad, the cars’ braking ability was of critical importance, as an uncontrolled descent would likely have had deadly consequences. To prevent this, the cars had several independent braking systems. Each car was equipped with standard trolley brakes, but the cable itself was controlled by a centrifugal governor at the summit that automatically slowed the cable once it began moving faster than 1,400 feet per minute, or about 16 miles per hour. This second feature obviously only worked if the cable remained intact, but there was yet another braking system in the event of a catastrophic failure of the cable. As shown in the first photo, a third rail ran inside the tracks next to the cable. In an emergency, the motorman could activate a lever that would cause the car to clamp on to this rail. This could also be done automatically, by a governor that was set to engage the rail once the car exceeded 1,500 feet per minute, or 17 miles per hour.

In any funicular railway, one of the other challenges is determining how the two cars will pass each other. The simplest solution is to have two parallel tracks, with each car operating on its own track at all times. However, this requires a wider right-of-way, along with significantly more materials than a single-track railway. One alternative is a three-rail funicular, in which each car has its own outside rail and shares the middle one, diverging only at a short passing section. The other option is to have one track for both cars, with a turnout at the halfway point. This requires the least amount of land and materials, but it requires a complex track arrangement at the turnout to ensure each car takes the correct path and safely crosses over the cable.

Here on Mount Tom, the railroad engineers chose the third option, as shown in the first photo. The two cars met at a passing loop, which is visible in the lower center of the photo. At first glance it looks similar to a standard railroad switch, but the key difference is that it has no moving parts. Instead, the cars and tracks are designed so that each one can only take one path, which remains the same regardless of whether the car is heading up or down the mountain. As such, the Rowland Thomas always took the tracks on the north side (the left side when viewed from this direction), while the Elizur Holyoke always took the south side.

To achieve this, the two cars had different wheel arrangements. The wheels on one side of the car had a wider tread than on the other side, which caused them to be guided along deflector rails onto the correct track. For the Rowland Thomas, these wide-tread wheels were on the left side when it was headed uphill, and for the Elizur Holyoke they were on the right side. On the same side as these wheels, each car also had an extra set of wheels that were slightly raised above the others and hung out about 15 inches from the main wheels. Because the turnout required gaps in the main rail to allow the cable to pass through, there was a short section of rail next to these gaps. As the main wheels approached the gap, the auxiliary wheels would roll along this additional rail, preventing what would otherwise be a derailment.

Work on the railroad began in March 1897, and it was completed in time for the summer season, opening on May 25. It operated throughout the summer and into the fall foliage season, before closing for the winter at the end of October. Round trip fare was 25 cents, and included the trolley ride along with use of the Summit House. The trolleys were scheduled to run twice an hour, with extra trips as needed. However, by September this schedule was insufficient to keep up with demand, as indicated by a Springfield Republican article that criticized the railroad for dangerously overcrowded trolleys.

During the early years of the railroad, perhaps its most distinguished passenger was President William McKinley, who visited Mount Tom along with his wife Ida on June 19, 1899. A number of onlookers gathered at the lower station to catch a glimpse of the president, who sat in the front seat of the Elizur Holyoke trolley for the ride up the mountain. At the summit, he and Ida were likewise greeted by a large crowd, and they spent about an hour there, where they ate a light lunch at Summit House before heading back down the mountain.

As it turned out, the McKinleys would be the first of at least two presidential couples who would travel up the Mount Tom Railroad. About five years later, a young Calvin Coolidge and Grace Goodhue visited the mountain on a date. At the time, Calvin was a lawyer in Northampton and Grace was a teacher at the Clarke School for the Deaf. While at the Summit House, he purchased a souvenir plaque of the mountain, which became the first gift he ever gave her. They subsequently married in 1905, and he went on to become governor, vice president, and then ultimately president in 1923.

In the meantime, the original Summit House only lasted for a few years before being destroyed by a fire in 1900. Its replacement opened the following year, but this too would eventually burn, in 1929. By contrast, the Mount Tom Railroad itself appears to have avoided any major incidents throughout its history. However, there were occasional breakdowns that forced passengers to walk down the mountain, and in at least one instance causing a number of people to spend the night in makeshift accommodations at the Summit House.

On July 24, 1928, at around 9:15pm, the Rowland Thomas had to stop about 150 feet from the upper station because of a broken journal on one of its axles. This likewise caused the Elizur Holyoke to stop the same distance from the lower station. The passengers on the Elizur Holyoke were able to easily return to the station, but about 50 people were stranded at the summit. Many chose to walk down the mountain in the dark, guided by railroad employees with lanterns, but 22 remained at the Summit House overnight. Some stayed up all night, playing bridge and dancing, and most descended the mountain after sunrise, although four guests stayed at the summit until railroad service was restored later in the day. A similar incident occurred less than a month later, when a spread rail stopped the trolleys at about 9:00pm. This time, 35 people walked down in the dark, but it does not appear that anyone spent the night at the summit.

After the 1929 fire at the Summit House, the railroad quickly constructed a temporary replacement at the summit. It had intended to then build a more permanent structure, but by the early 1930s the mountain faced declining numbers of visitors. Part of this was because of the Great Depression, which began just months after the fire here. Another factor was increased car ownership among the middle class, which meant that recreational activities were no longer limited to places that people could access by trolley.

At the base of the mountain, Mountain Park would remain a popular amusement park for decades, but both the Mount Tom Railroad and the Summit House closed in the late 1930s. The temporary Summit House was dismantled for scrap metal in 1938, and around the same time the railroad tracks were taken up and removed. The rails and other metal components were presumably reused or scrapped, but the wooden ties were discarded in piles alongside the right-of-way. More than 80 years later, many of these ties are still in remarkably good condition, and a few are visible in the lower right corner of the second photo.

The railroad ultimately sold the summit area and the right-of-way to the WHYN radio station, which constructed radio towers and transmitter buildings on the site of the old Summit House. The old railroad grade was paved over, and it became an access road for the radio station. As a result, the present-day scene looks very different from the first photo, although there are still a few remnants of the old railroad, including the ties, some discarded spikes, and metal support braces for the old utility poles that once supported the electrified trolley wire.