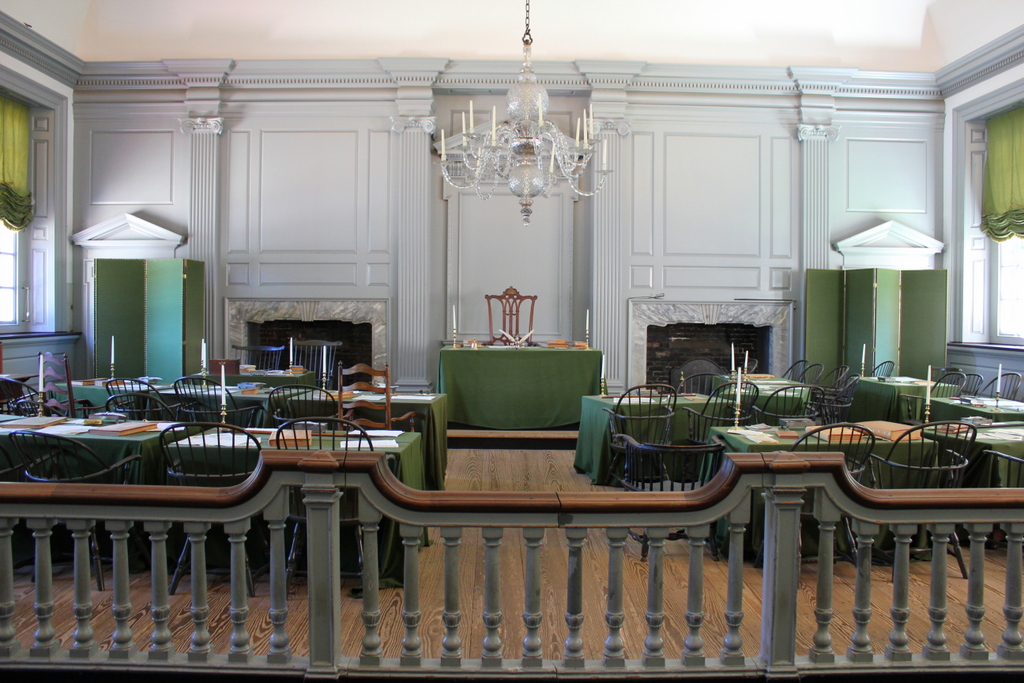

The Assembly Room on the first floor of Independence Hall, around 1905. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

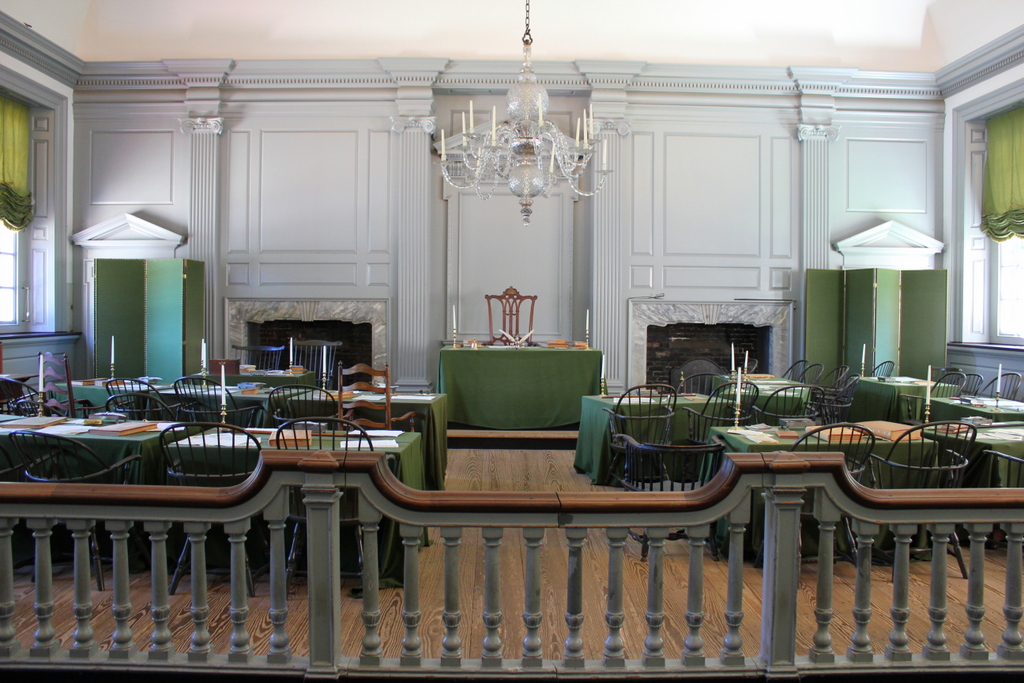

The room in 2018:

As discussed in an earlier post, Independence Hall was completed in 1753 as the Pennsylvania State House, the colony’s first capitol building. The first floor consisted of two large rooms on either side of a central hall. To the west was the courtroom for the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, while the room on the east side, which is shown here, housed the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly. As a result, this room was known as the Assembly Room, and it was the meeting place of the colonial legislature – and later the state legislature – throughout the second half of the 18th century. However, this room is most remembered for housing the Continental Congress from 1775 to 1783, and for being the site of the signing of the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution.

Philadelphia had played a central role in the American Revolution since 1774, when the First Continental Congress convened in the city from September 5 to October 26 of that year. The city served as a convenient meeting place between the northern and southern colonies, but the delegates met at the recently-constructed Carpenters’ Hall, instead of here at the State House. It was not until the Second Continental Congress, which convened on May 10, 1775, that the colonial delegates would meet here in the Assembly Room of what would become known as Independence Hall.

When these delegates arrived here for the Second Continental Congress, the American Revolution was less than a month old, having started on April 19 with the Battles of Lexington and Concord. As a result, the Congress soon began to exercise control over the colonial military, starting with the creation of the Continental Army on June 14 and the appointment of George Washington as its commanding officer. Washington, who was part of the Virginia delegation here in Congress, was nominated for the position by John Adams, and Washington subsequently left for Boston to assume command of the army.

Another important congressional action occurred less than a month later, on July 8, when the delegates approved the Olive Branch Petition. Intended as a peace overture to Britain, in order to appease the more conservative members, this petition was summarily rejected by the British government. However, it proved significant in highlighting the fact that Britain was not receptive to compromises, which gave the more radical members a stronger case in favor of declaring independence.

Even so, it would take nearly another year before the Continental Congress finally declared independence. The resolution, known as the Lee Resolution after its sponsor, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, was introduced here on June 7, 1776. In the ensuing weeks, the idea of independence was debated, a draft declaration was written, and the resolution finally passed on July 2, after last-minute actions to secure yes votes from South Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Delaware.

John Adams, who was among the delegates in attendance, believed that this day would be celebrated by future generations as Independence Day. As it turned out, though, it ended up being July 4 – the day when Congress approved the final wording of the Declaration of Independence – that would be remembered as such. However, despite popular images of the Founding Fathers lining up here to sign the document, no such scene actually occurred on that day. Instead, historians generally identify August 2 as the date when most delegates signed, although some signatures would be added as late as November.

Following the Declaration of Independence, Congress continued to meet here throughout most of the war, with two interruptions during British occupations of Philadelphia. The first occurred from December 1776 through March 1777, when Congress met in Baltimore, and the second lasted from September 1777 to July 1778, with Congress meeting in Lancaster for one day and then York, Pennsylvania for the duration. The Articles of Confederation, the nation’s first constitution, was written while Congress was in York, but it did not go into effect until 1781, when Maryland signed it here in the Assembly Room of Independence Hall.

Under the Articles of Confederation, the Continental Congress did not see significant change. It remained a unicameral legislature, with each state having one vote regardless of population, and it continued to meet here in Independence Hall for several years, making this the de facto national capitol building. However, Congress’s time here was cut short by a dispute between it and the state government of Pennsylvania, which also occupied this building. In June 1783, a mob of about 400 American soldiers descended upon Independence Hall, demanding payment for their wartime service. Congress asked the state’s Supreme Executive Council to call in the militia to suppress the riot, but the state declined, and Congress left the city on June 21.

When Congress reconvened nine days later, it was at Nassau Hall in Princeton, New Jersey. Over the next few years, Congress would also meet in Annapolis, Trenton, and then in New York City, which became the national capital until 1790. Congress would never return here to Independence Hall, but this room would play one more important role in the national government in 1787, when the Constitutional Convention met here from May 25 through September 17, 1787. Although officially intended to “revise” the heavily flawed Articles of Confederation, this convention ultimately created a completely new blueprint for the national government, and the current United States Constitution was signed here on September 17, by delegates from 12 of the 13 states.

The Constitutional Convention became famous for its many compromises, with delegates seeking to strike a balance between the large states and small states, and between the north and the south. Perhaps the most important was the Connecticut Compromise, which established a bicameral legislature, with equal representation in the Senate and proportional representation in the House. The proportional representation caused another controversy, though, with regards to how slaves should be counted for representation purposes. This was resolved by the Three-Fifths Compromise, which counted three-fifths of the slave population toward Congressional representation, thus preventing southern states from becoming too dominant in national politics.

The end of the Constitutional Convention also marked the end of this room’s use for national political gatherings. The new Constitution went into effect in 1789, and a year later the national government returned to Philadelphia for a ten-year period, while Washington, D.C. was being developed. However, during this time period Congress met next door in Congress Hall, while the Supreme Court met in a matching building on the other side of Independence Hall. In the meantime, the Assembly Room here in Independence Hall would continue to be used by the state legislature, but in 1799 the state capital was moved to Lancaster, leaving this building largely vacant.

During the early 19th century, parts of Independence Hall were used by artist Charles Willson Peale, who established a natural history museum and portrait gallery here. The building was nearly demolished in the 1810s, but it was instead purchased by the city of Philadelphia. Early in the city’s ownership, the original paneling here in the Assembly Room was removed, but the room was subsequently restored by noted architect John Haviland in 1833. However, this restoration, which is shown in the first photo some 70 years later, was not entirely accurate, and was largely based on the appearance of the adjacent Supreme Court Room.

Throughout the 19th century, the Assembly Room was used for a wide variety of purposes. Many patriotic events were held here, with distinguished visitors such as Henry Clay, Andrew Jackson, and Abraham Lincoln. The bodies of both Clay and Lincoln would later lay in state here in this room, as did the body of John Quincy Adams following his death in 1848. In addition, this room was also used as a museum, displaying a number of objects relating to American Revolution. During the second half of the 19th century, the Liberty Bell was on display here, before being moved to the base of the tower, and the room also housed a large collection of Charles Willson Peale’s portraits. Some of these are visible in the first photo, including his famous George Washington at Princeton, which stands in the corner on the left side of the scene.

The Assembly Room later underwent a second major renovation in the mid-20th century, restoring it to its presumed 18th century appearance. The room was also furnished during this time, although almost none of the objects are original to the room. Today, there are only two artifacts that survive from the Revolutionary period. The oldest of these is the Syng inkstand, which sits on the table at the front of the room in the present-day scene. Made in 1752, this inkstand was used in the signing of both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, and it is visible in the first photo, in a small display case in front of the fireplace on the left side.

The other object, and the only surviving piece of furniture from the 18th century, is the chair in the center of the room, which is visible in both photos. This was made in 1779, and it was the seat where George Washington sat while presiding over the Constitutional Convention. It is often known as the Rising Sun Armchair, because of the carved sun on the top of it. This decoration caught the attention of Benjamin Franklin during the Constitutional Convention, and he remarked on it as the delegates were signing the document. His words, which were recorded in James Madison’s notes, provided a fitting conclusion to the convention that marked a new beginning for the United States:

Whilst the last members were signing it Doctr. Franklin looking towards the Presidents Chair, at the back of which a rising sun happened to be painted, observed to a few members near him, that Painters had found it difficult to distinguish in their art a rising from a setting sun. I have said he, often and often in the course of the Session, and the vicisitudes of my hopes and fears as to its issue, looked at that behind the President without being able to tell whether it was rising or setting: But now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting Sun.