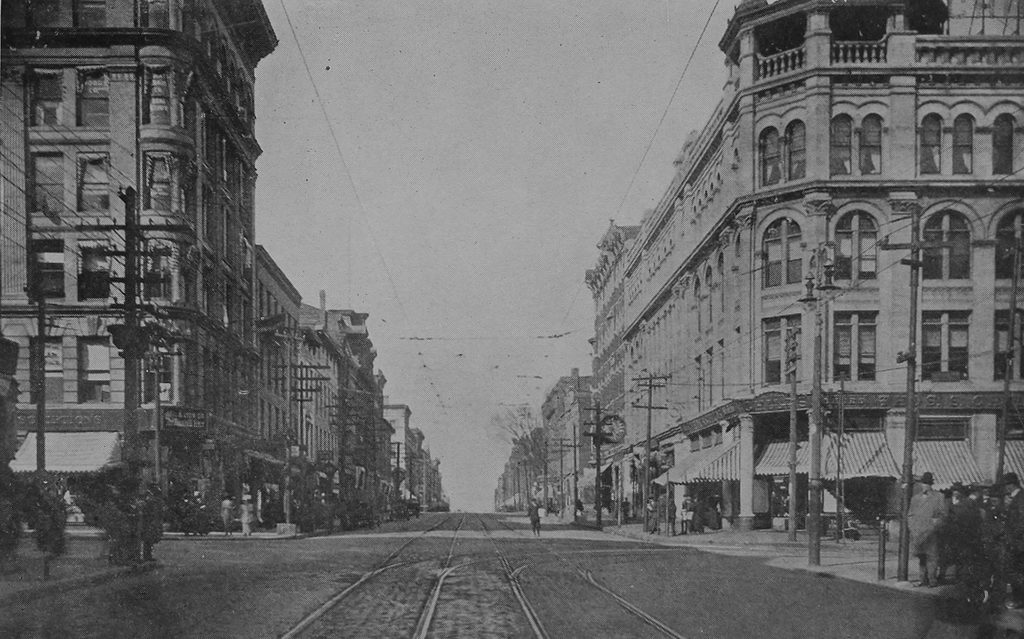

The building at the corner of High and Suffolk Streets in Holyoke, around 1910-1915. Image from Illustrated & Descriptive Holyoke Massachusetts.

The scene in 2017:

This four-story commercial block was built sometime in the late 19th century, probably after 1884, since it does not appear on the city atlas for that year. However, by the early 20th century it was owned by Margaret Cunningham, whose husband Charles was a liquor dealer. Charles was an immigrant from Canada who came to the United States as a teenager, and he operated Cunningham & Co. Liquors out of the storefront on the right side of the building. The first photo was taken sometime around 1910-1915, and was featured in Illustrated & Descriptive Holyoke Massachusetts, which includes a glowing description of Cunningham’s business:

To those who are acquainted with the standing of the principal mercantile establishments of Holyoke, the leading position of this house in its line is a matter of common knowledge. To others who are not so well informed a visit to the place of business and an inspection of the fine stock of goods handled here will convey a good idea of its importance. Cunningham and Company are extensive importers of wines, gins and brandies, and are also wholesale and retail dealers in whiskeys, ales and liquors of the best brands. They have been engaged successfully in this business ever since the date of its establishment, twenty years ago. A specialty of supplying fine goods to clubs, restaurants, hotels, and other first-class consumers, in which branch of the business they are known to excel. They also have a handsomely appointed bar, where they supply an active trade at retail. Competent assistants are employed and courtesy and consideration is extended to all.

The first photo also shows The Toggery Shop, which was located in the corner storefront on the left side of the building. This men’s clothing store was similarly lauded in Illustrated & Descriptive Holyoke Massachusetts, which notes that:

This company is one of the hustlers in the haberdashery and gents’ furnishing goods line in the city of Holyoke. Its flourishing business has been in operation here for the past ten years and in that time it has made a host of friends who by their staunch and loyal patronage have contributed largely to its success. These ten years of strenuous and lively competition with stores of its class have made this one wide-awake and very much alive to up-to-date lines of goods and progressive methods. Eternal vigilance is exercised by Mr. Murray in the selection of his stock and discrimination buyers may feel assured that any goods purchased at this store will be up-to-date in styles and patterns and the prices are right. The leading makes of hats, neckwear, hosiery, gloves, underwear, etc. are well represented here in a choice and varied assortment. The store is in a good location for business and presents a neat and attractive appearance at all times, with its complete equipment of modern fixtures and furniture.

Today, many of Holyoke’s historic commercial blocks are still standing along High Street, but the Cunningham Building is not one of them. Its exact fate seems unclear, but it was evidently gone by the mid-1970s. The current building was completed around this time, and features a Brutalist-style brick and concrete exterior that contrasts sharply with the ornate Italianate-style design of its predecessor. Both the haberdashery and the liquor wholesaler are also long gone from this location, and the current building is now occupied by Peoples Bank.