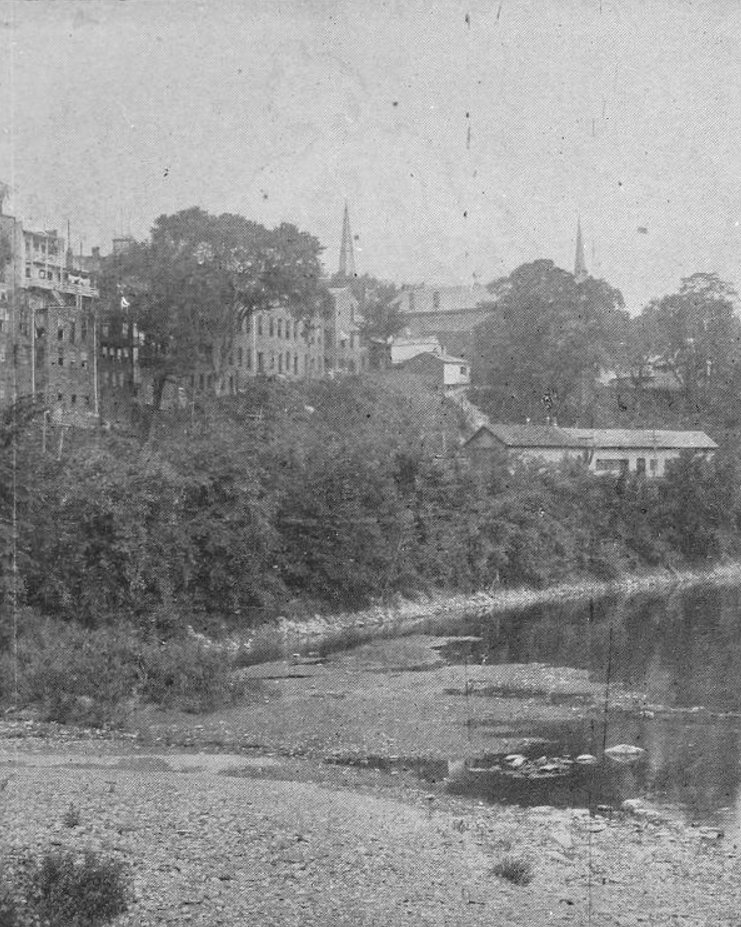

The house at 80 Linden Street, at the corner of Chapin Street in Brattleboro, around 1894. Image from Picturesque Brattleboro (1894).

The house in 2017:

John Holbrook was born in 1761 in Weymouth, Massachusetts, but as a young man he moved to Vermont, where he found work as a surveyor in what was, at the time, largely uncharted territory. He originally settled in Newfane, where he later ran a general store, but he subsequently moved to Brattleboro, where he continued his business career. Holbrook was affiliated with merchants in Hartford, Connecticut, and in 1811 he relocated to East Windsor. However, he only remained in Connecticut for a few years, returning to Brattleboro soon after the death of his son-in-law, William Fessenden, in 1815. Upon returning, Holbrook took over Fessenden’s publishing company, and he was also selected as a church deacon.

Holbrook had no prior experience in the publishing industry, but he grew the company into a prosperous business, which specialized in producing Bibles. Although located far from the major commercial centers of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, Holbrook’s Brattleboro-based business fared well in competition with the more established publishing houses in the major cities. His Bible proved popular, thanks in part to its quality paper and abundant illustrations, and over the next few decades he and his firms would produce 42 different editions.

Holbrook retired in 1825, and moved into this newly-built home in the northern part of the downtown area. It was designed and built by local builder Nathaniel Bliss, with a Federal-style design that was likely inspired by the works of Asher Benjamin, a prominent New England architect who published a number of architectural handbooks in the early 19th century. As was usually the case in Federal architecture, the front facade is nearly symmetrical, with the only exception being the off-centered front door. The house also includes a distinctive, and somewhat unusual front porch, although it does not seem clear as to whether this was part of its original design.

By the time John Holbrook and his wife Sarah moved into this house, most of their ten children were already grown. The youngest, Frederick, was born in 1813 during the family’s brief residence in Connecticut, but spent most of his childhood in Brattleboro. He was about 12 when this house was built, and presumably lived here for at least a few years before leaving to attend school. Returning to Brattleboro after a tour of Europe in 1833, Frederick became a farmer, eventually serving as the president of the Vermont State Agricultural Association for eight years. Along with this, he also had a career in politics, serving in the state legislature from 1849 to 1850, and as governor from 1861 to 1863.

In the meantime, John Holbrook lived here in this house until his death in 1838, and his widow Sarah sold the property three years later, to Dr. Charles Chapin. Originally from Orange, Massachusetts, Dr. Chapin attended Harvard, and he subsequently began practicing medicine in Springfield, Massachusetts. His first wife, Elizabeth, died only a few years after their marriage, and in 1830 he remarried to Sophia Dwight Orne, the granddaughter of prominent Springfield merchant Jonathan Dwight. A year later, the couple relocated to Brattleboro, where Dr. Chapin became a businessman and a government official. His long career included serving in the state legislature and as a U.S. Marshal, and he was also a director of the Vermont Mutual Insurance Company and the Vermont Valley Railroad.

Dr. Chapin had one child, Elizabeth, from his first marriage, and he had five more children with Sophia: Lucinda, Oliver, Mary, William, and Charles. All but the youngest were born before the family moved into this house, but they all would have spent at least part of their childhood here. The two older sons, Oliver and William, would later go on to serve in the Civil War, and William spent time in the notorious Libby Prison in Richmond, after being captured by Confederates. By the 1870, their widowed daughter Mary was their only child still living here with them. The census of that year shows Charles with a net worth of 40,000 – a considerable sum equal to nearly $800,000 today – while Sophia had $25,000 of her own, possibly an inheritance from her wealthy Dwight relatives.

Dr. Chapin died in 1875, and Sophia died five years later. Shortly after, the property behind the house was sold and subdivided. Chapin Street was opened through the property, just to the left of the house, and was developed with new houses by the late 1880s. The first photo was taken only a few years later, and one of the new houses can be seen in the distance on the far left. However, the old Holbrook and Chapin house remained standing, even as the surrounding land was divided into house lots for the growing town population.

Today, the house’s exterior is not significantly different from when the first photo was taken over 120 years ago. Although now used as a commercial property, the house has remained well-preserved as a good example of late Federal-style architecture, and as one of Brattleboro’s finest early 19th century homes. Because of this, in 1982 the house was added to the National Register of Historic Places.