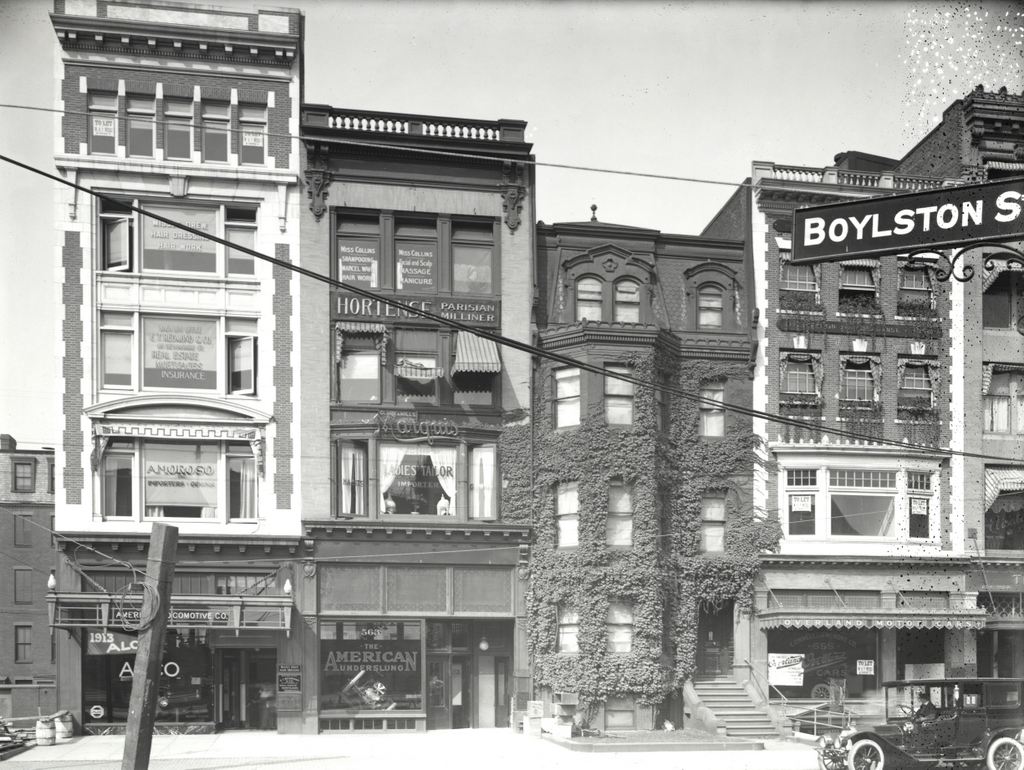

The Museum of Natural History building on Berkeley Street in Boston, around 1904. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The building in 2015:

This historic building on Berkeley Street is one of the oldest buildings in the Back Bay neighborhood. It was constructed in 1863 on a block that was set aside for the Museum of Natural History and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Eventually, two MIT buildings would be built in this block between Berkeley and Clarendon Streets, the first of which was the 1866 Rogers Building. The Rogers Building’s architecture matched the Museum of Natural History, and it can be clearly seen in the distance in the first photo.

MIT remained here until 1916, when they relocated to their much larger campus across the Charles River in Cambridge. The Rogers Building, along with the neighboring Walker Memorial Building, were demolished in 1939 to build the New England Mutual Life Insurance Building, which is still standing in the distance in the 2015 photo. The museum was located in this building until 1951, when it was renamed the Boston Museum of Science and moved to its present location on the Charles River. After the museum left, it has been used by several different companies as a retail store, including Bonwit Teller and Louis Boston. In 2013, the home furnishing company Restoration Hardware opened their Boston gallery in the building, which still remains well-preserved and relatively unchanged after over 150 years and a number of ownership changes.