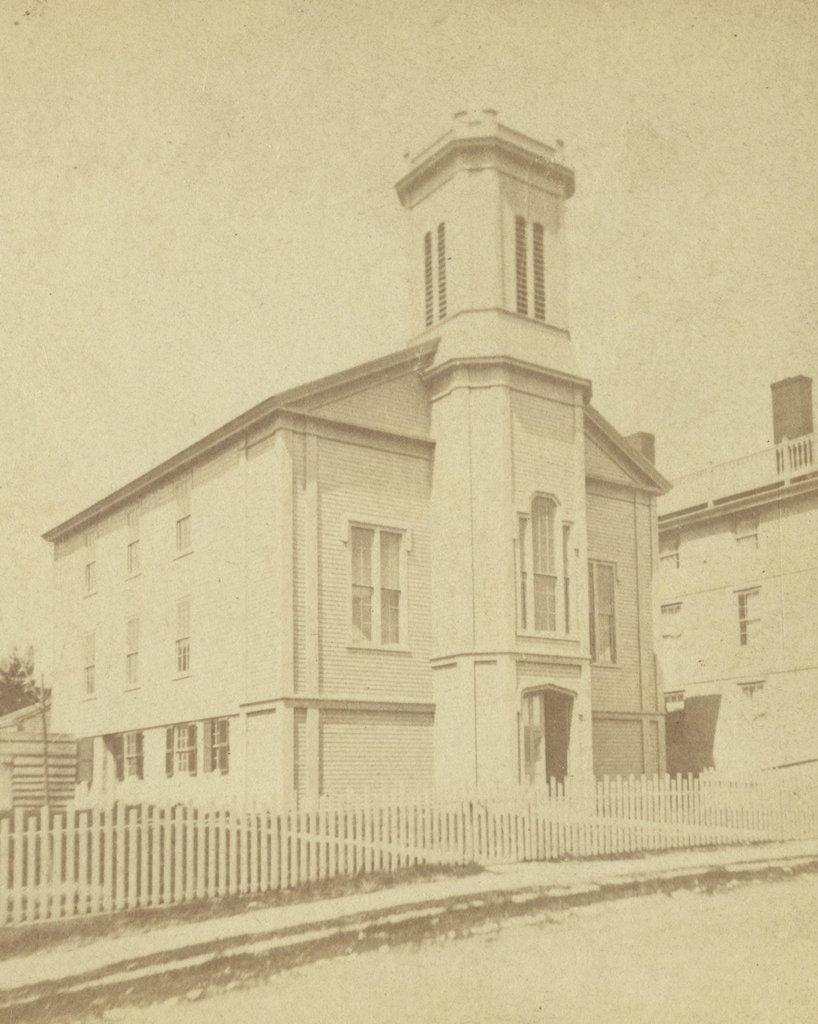

The Seamen’s Bethel on Johnny Cake Hill in New Bedford, around the 1860s-1880s. Image courtesy of the New Bedford Free Public Library.

The scene in 2022:

These two photos show the Seamen’s Bethel, perhaps the most famous whaling landmark in New Bedford. Its fame is derived largely from Herman Melville’s description of it in Moby Dick, but it also played an important role in the New Bedford whaling community. During much of the early 19th century, New Bedford was the world’s leading whaling port. From here, ships would embark on multi-year voyages around the world, and would—hopefully—return with their cargo holds filled with whale oil, spermaceti, and whalebone.

Whaling was inherently dangerous, not only because of the risks associated with long sea voyages in general, but also because of the dangers involved in trying to kill whales from small, easily swamped boats in the middle of the ocean. Crews were often a diverse mix of different ethnicities and nationalities, including former slaves who saw whaling not only as a means of employment, but also as a way to avoid recapture by their enslavers.

However, as was the case in any major port city, there were many in New Bedford who were concerned about how these whaling crews spent their leisure time when they were ashore. Sailors were typically paid a certain percentage of the profits at the end of the voyage, which meant that they returned to New Bedford flush with cash. And, after several years at sea, many sailors saw the city’s saloons, brothels, and gambling houses as ideal places to spend that hard-earned money.

In an effort to combat these vices, some residents took to vigilante action and occasionally destroyed notorious brothels. Others, however, took a more proactive approach, establishing the New Bedford Port Society for the Moral Improvement of Seamen in 1830. Two years later, in 1832, the organization constructed the Seamen’s Bethel on Johnny Cake Hill, which is shown here in these two photos. The goal was to provide a nondenominational chapel that would welcome a diverse population of sailors and meet their spiritual needs.

The building was dedicated on May 2, 1832, with a ceremony led by the Reverend Edward Taylor of the Seamen’s Bethel in Boston. A former sailor with little formal education, Taylor was nonetheless a popular preacher who was known for his engaging and colorful sermons. His ministry in Boston focused primarily on sailors, but he was also highly regarded by the literary elite of the 19th century, including those who tended to take a dim view on organized religion, such as Charles Dickens, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Walt Whitman.

The first chaplain here at the Seamen’s Bethel in New Bedford was the Reverend Enoch Mudge. He was a Methodist minister, but in keeping with the nondenominational goals of the organization, he respected the various beliefs of the sailors of New Bedford. Among the sailors who heard him preach here was 21-year-old Herman Melville, who attended Sunday services on December 27, 1840, a week before he departed on the whaling ship Acushnet. He would spend the next few years at sea, and his experiences as a crewman on a whaling ship would help form the basis for his famous novel Moby-Dick, which was published in 1851.

The Seamen’s Bethel features prominently in the beginning of Moby-Dick, and it is the subject of chapters seven through nine, which are titled “The Chapel,” “The Pulpit,” and “The Sermon.” At the beginning of chapter seven, the narrator Ishmael enters the building on a stormy winter day, and provides the following description of the Bethel:

In this same New Bedford there stands a Whaleman’s Chapel, and few are the moody fishermen, shortly bound for the Indian Ocean or Pacific, who fail to make a Sunday visit to the spot. I am sure that I did not.

Ishmael goes on to describe the interior, including the marble monuments to various New Bedford sailors who were lost at sea. Such monuments do in fact exist here at the Seamen’s Bethel, but other interior features were completely fictional, including a pulpit that was shaped like the bow of a ship. Ishmael then describes Father Mapple, the fictional chaplain of the Bethel. His character is often considered to be based on Edward Taylor, but it also seems plausible that Melville based at least some of it on Enoch Mudge and the sermon that he heard here in 1840.

Over the years, the Port Society expanded its activities beyond just the Seamen’s Bethel. In 1851, Sarah Rotch Arnold donated her late father’s house to the society. It was then moved to the lot directly to the left of the Bethel, as shown in these two photos. It became the Mariners’ Home, a boarding house that offered accommodations to sailors. It was run by the Ladies Branch of the Port Society, and it provided an alternative to the city’s less reputable boarding houses, which were often located alongside the saloons and brothels in the red light districts.

The Bethel sustained significant damage in a fire in 1866, but it was subsequently repaired, and the first photo was likely taken at some point afterwards. It would continue to serve the spiritual needs of sailors for many years, but the decline in the New Bedford whaling industry helped to shift the society’s focus to some extent. As noted in the 1918 History of New Bedford, “[w]ith the decline of New Bedford as a port of entry, the society became more general in its character as mission, as at present.”

In the meantime, the popularity of Moby-Dick helped to draw attention to the Seamen’s Bethel, and over the years it became a major New Bedford landmark, especially after the 1956 film adaptation of the novel. So famous was Melville’s description of the chapel that, in 1961, the Port Society even altered the interior to make it conform with the novel by installing a bow-shaped pulpit. This wasn’t necessarily the best move from a historic preservation perspective, but it is certainly an example of the concept of life imitating art.

Today, very little has changed here in this scene. The Port Society is still an active organization, and still owns both the Seamen’s Bethel and the adjacent Mariners’ Home. Both buildings are well preserved overall, and they are located within the New Bedford Whaling National Historical Park, where they stand as reminders of the city’s heyday as a whaling port.