The house at 201 Maple Street in Springfield, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

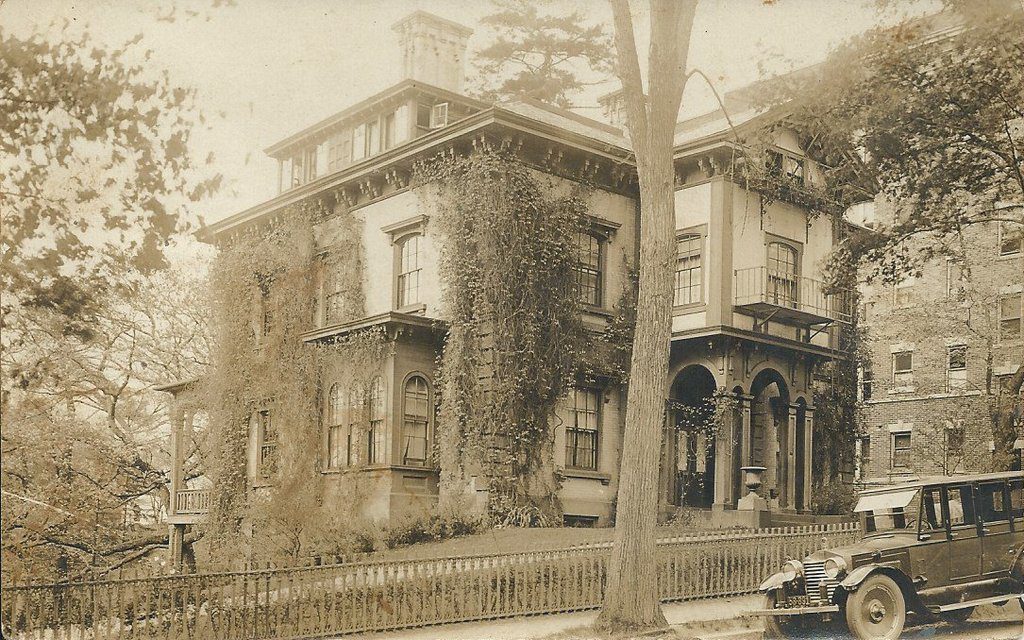

The house around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The house in 2017:

Homer Foot was born in 1810, and was the son of Adonijah Foot, the master armorer at the Armory. However, Adonijah died in 1825, a few months after 14-year-old Homer began working as a clerk at the Dwight store, at the corner of Main and State Streets. At the time, the Dwight family was one of the leading families in Springfield, and their merchant business was among the oldest and most prosperous in the region. The firm was owned by many successive generations of Dwights, who sold dry goods, groceries, and hardware from their corner store. By the time Homer began working here, longtime owner James Scutt Dwight had recently died, but his son, James Sanford Dwight, took over the firm along with several other partners.

Homer worked as a clerk for James Sanford Dwight for six years, but in 1831 Dwight died from malaria at the age of 31, while vacationing in Italy. His untimely death marked the end of many years of Dwight ownership of the company, and later in 1831 it was sold to 21-year-old Homer Foot. Even then, though, the business did not entirely leave the family, because three years later he married Delia Dwight, the sister of his late employer. They were married at the old Dwight homestead at the corner of State and Dwight Streets, in a double wedding ceremony that also included Delia’s sister Lucy and her husband, William W. Orne.

Early in their marriage, Homer and Delia lived in a house at 41 Maple Street, right next to where the South Congregational Church was later built. However, in 1844 he hired master builder Simon Sanborn, Springfield’s leading architect of the first half of the 19th century, to design a house on the hill at the corner of Maple and Central Streets. Foot was among the first of Springfield’s wealthy residents to move to the upper part of Maple Street, which was further from downtown but offered dramatic views of the surrounding landscape. The design of the house itself was also a departure from Springfield’s conventional architecture. Most of the homes in this era were fairly plain, conservative Greek Revival-style homes, but Sanborn designed a large, Gothic Revival-style house that reflected the Victorian-era shifts toward more elaborate, ornate architecture.

Shortly after the completion of his house, Foot embarked on an even more ambitious building project. For many years, the Dwight store had been located in an old brick building at the northeast corner of Main and State Streets, where the MassMutual Center is now located. However, in 1846 he purchased the old Warriner’s Tavern, which was located diagonally across the street. Once the leading tavern in Springfield, this colonial-era building was obsolete by the mid-19th century, and owner Jeremy Warriner had moved his business to the nearby Union House. The old tavern building itself was moved off the property, a little to the west along State Street, and Homer Foot built his new store on the site.

Aside from his own business, Foot was also involved in several other local companies, serving as a director of the Pynchon Bank, auditor for the Springfield Institution for Savings, and treasurer of the Hampden Watch Company. He was also a lieutenant colonel in the state militia, but unlike many of the city’s other prominent businessmen of the era, he never held public office, aside from serving as one of the overseers of the poor. However, this did not stop the Whig party from nominating him, against his wishes, as their candidate for lieutenant governor in 1856, although he ended up finishing a distant third in the general election.

Homer and Delia raised their ten children here in this house, and they went on to live here for the rest of their lives. They were both still living here when the first photo was taken in the early 1890s, but Delia died in 1897, and Homer died a year later. By this point, the upper part of Maple Street has become one of the most desirable neighborhoods for the city’s wealthiest residents, and in 1901 the house was purchased by Andrew Wallace, the co-founder and owner of the Springfield-based Forbes & Wallace department store.

Andrew Wallace was born in Scotland in 1842, and immigrated to the United States in 1867, where he found work in Boston with the dry goods firm of Hogg, Brown & Taylor. From there, he moved to Pittsfield and then to Springfield, where in 1874 he partnered with Alexander B. Forbes to establish Forbes & Wallace. Like Homer Foot & Co. a generation earlier, Forbes & Wallace became the city’s leading retail company, with a large store on Main Street in the heart of downtown Springfield.

Andrew Wallace, his wife Madora, and their six children had previously lived in a fine Second Empire-style mansion on Locust Hill, at the corner of Main and Locust Streets in the South End, but in 1901 he purchased this house from Homer Foot’s heirs. By this point, the house was nearly 60 years old, and Gothic-style architecture had long since fallen out of fashion, so Wallace expanded and remodeled the house, adding a large wing that dominates the foreground of the two 20th century photos. Along with this, he added a large stable on the other side of the house, which included a recreation room on the second floor. The result was an interesting mix of architectural styles, which included many of the original Gothic details, combined with a new stucco exterior and tile roof.

After Andrew’s death in 1923, his son Andrew Jr. inherited the house, where he lived with his wife Florence and their children, Andrew and Barbara. During the 1930 census, they lived here with three servants, and the house was valued at $100,000, equivalent to nearly $1.5 million today. They were still living here later in the decade, when the first photo was taken, and Andrew was working as the president of Forbes & Wallace, which remained a retail giant in the region for many more decades, until it finally closed in 1976.

The Wallace family continued to live here until Florence’s death in 1951 and Andrew’s death five years later. The property was then sold to the MacDuffie School, a private school that was, at the time, located across the street at 182 Central Street. The house was converted into a dormitory, and was used by the school until the spring of 2011, when the school moved from Springfield to a new campus in Granby. Coincidentally, the move coincided with the June 1, 2011 tornado, which caused heavy damage to the Springfield campus, including the Foot-Wallace House. Many of the other buildings have since been restored, and the campus is now the home of Commonwealth Academy, but this house is still awaiting repairs, and remains boarded-up more than six years later. Because of this, the house has been included on the Springfield Preservation Trust’s annual listing of the city’s Most Endangered Historic Resources.