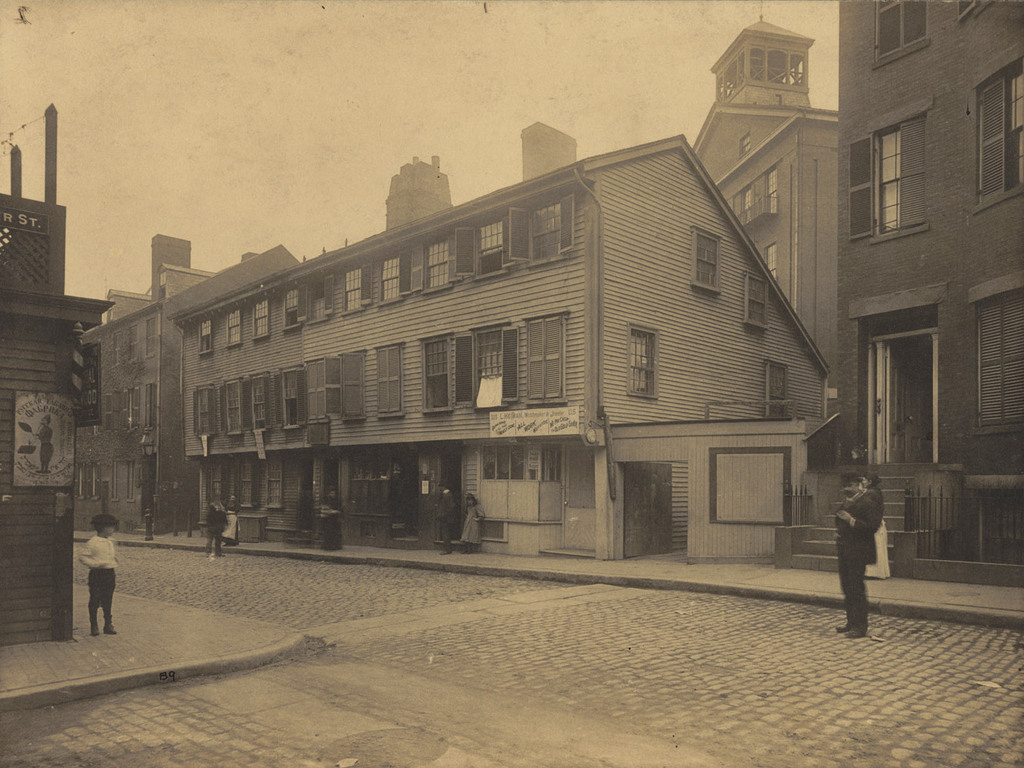

The John Tileston House, located at the corner of Prince and Margaret Streets, around 1898. Photo courtesy of Boston Public Library.

The scene in 2014:

A century before the first photo was taken, this house was the home of John Tileston, a teacher who taught writing at a nearby school from 1754 until 1819. During this time, teaching writing did not mean he taught his students to compose essays; he literally taught them how to write elegant script – an important skill for aspiring businessmen in the days before typewriters and word processors. Ever notice the quality of the penmanship on documents like the Constitution or the Declaration of Independence? It was teachers like Tileston who ensured that our nation’s founding documents weren’t written in chicken scratch. Interestingly, though, Tileston did it all with a disabled hand. His hand was severely burned in a fire as an infant, preventing him from doing most manual work but allowing him to teach instead.

His house stood long after his death, and in the first photo it had a first floor store that sold “Dry Fancy Goods,” as the sign above the door indicates. The house didn’t last much longer than that, though. Like many other colonial-era buildings in the North End, it was demolished to make way for new development in the first decade of the 20th century.