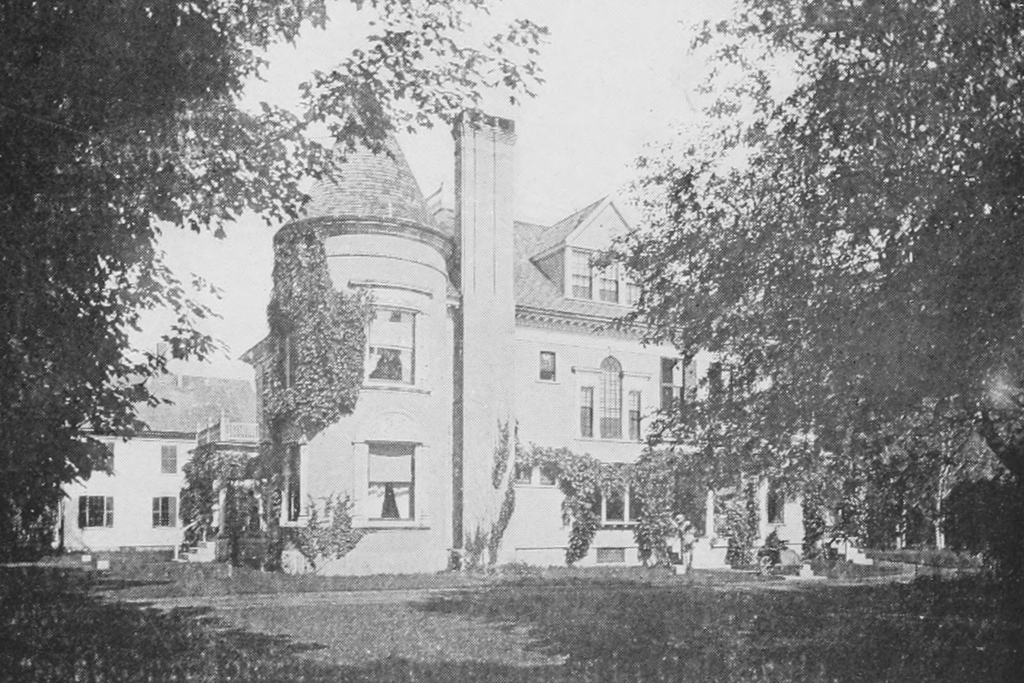

The house at 1627 Maple Street in Hartford, around 1900. Image from The Old and the New.

The scene in 2018:

This house was built in 1894 as the home of Ephraim Morris, one of the most prominent residents of late 19th century Hartford, Vermont. Morris was born in 1832, a little to the north of here in the town of Strafford, and he grew up in Norwich, where he attended Norwich University before moving to Boston to become a clerk in a boot and shoe firm. However, he ultimately returned to Vermont in 1854, settling in Hartford and joining his father Sylvester’s business. Later in the year, he married his wife, Almira M. Nickerson, who was originally from South Dennis, Massachusetts.

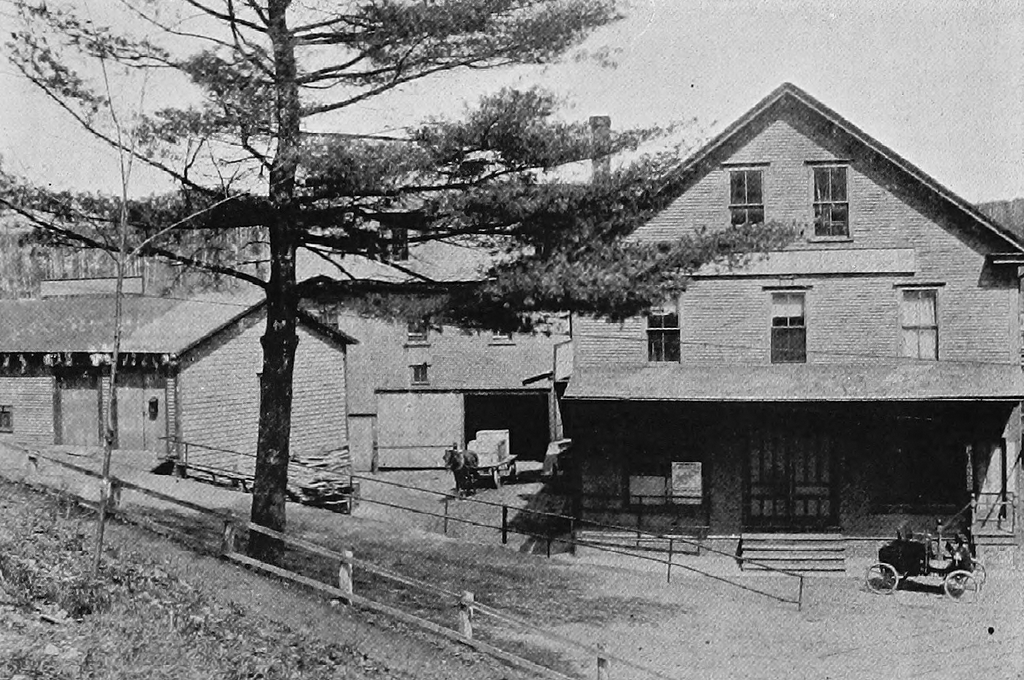

Sylvester Morris retired in 1857, and Ephraim carried on the business with his brother Edward. In the early years, they ground plaster and sold it for use as fertilizer, but they subsequently switched to manufacturing chairs. Then, later in the 19th century the brothers entered the woolen manufacturing industry, operating the Hartford Woolen Company along with the Ottauquechee Woolen Company in nearby North Hartland.

Aside from these businesses, Ephraim was also a director and vice president of the National Bank of White River Junction, and he represented Hartford in the state legislature from 1896 to 1898. However, perhaps his single most important contribution to the town came in 1893, when he donated $5,000 to build the Hartford Library. The library, which remains in use today, stands directly adjacent to the spot where, a year later, he built his own house.

Ephraim and Almira Morris had two daughters, Kate and Annie. Both attended Smith College, and Kate was in the school’s first graduating class, along with being the first to receive a Ph.D. from the school. She married Charles M. Cone in 1884, and they lived in a historic house just a little to the east of here in the center of Hartford. Annie, who was 14 years younger than her sister, was still living with her parents when they moved into this house in 1894, and she was still here during the 1900 census, shortly before her marriage to Roland E. Stevens.

The first photo was taken around this time, showing the side view of the house from the library grounds. The architecture of the house was primarily Colonial Revival in style, with distinctive elements such as the large Palladian window, but it also had some features from the earlier Queen Anne style, including the asymmetrical design and the turret at the southeast corner of the house.

Ephraim Morris died in 1901, followed by his widow Almira in 1909. Their daughter Annie subsequently inherited this house, and she lived here with her husband Roland for many years. He was a lawyer, and probably his most famous case came late in his life, when in 1952 he sued the state of Vermont on behalf the Iroquois tribe, claiming that much of the state’s land was unlawfully taken from them. The suit was ultimately unsuccessful, but both he and his case gained widespread attention in newspapers across New England.

Annie apparently died at some point in the 1950s, and Roland died in 1957 at the age of 89. Their large house was subsequently sold to the Bible Baptist Church, which converted it into a church. Since then, the building has been acquired by a different church, Praise Chapel, and it remains in use today. Despite these changes in use, though, the exterior of the building has remained well-preserved in more than a century since the first photo was taken, and it is now a contributing property within the Hartford Village Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1998.