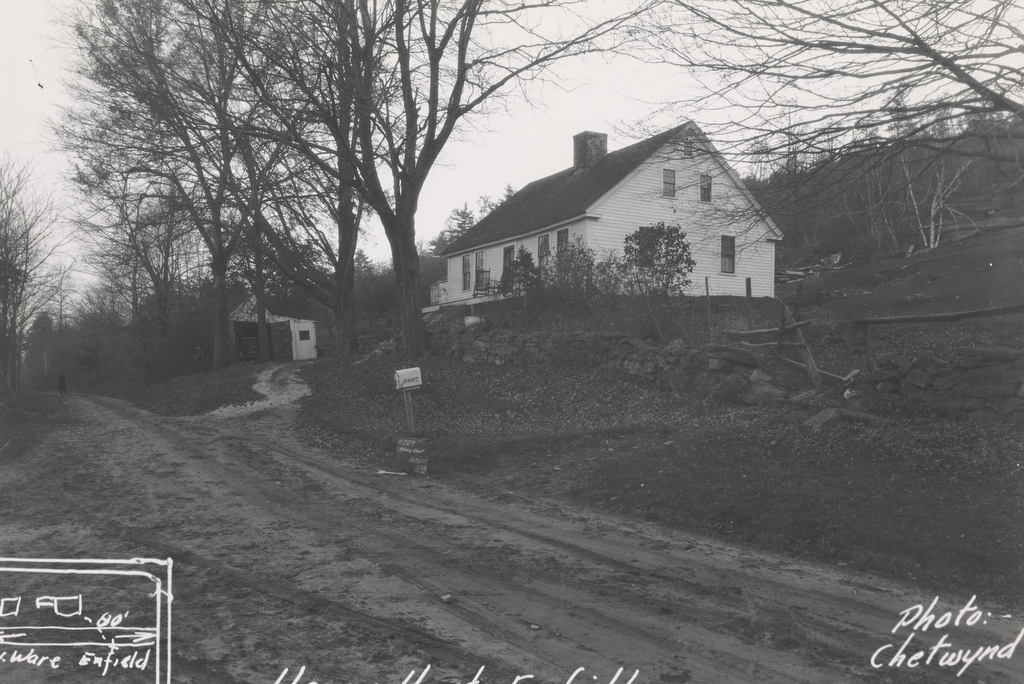

The house at 258 Mill Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The house in 2023:

Springfield was established by colonial settlers in 1636, making it by far the oldest community in Western Massachusetts. However, unlike nearly all of the other cities and towns in the area, it does not have any surviving buildings that have been verifiably traced back to the colonial period. Most of the colonial-era houses in Springfield were demolished during a period of rapid population growth in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and today there are only a few dozen buildings that predate 1850, with none that can be confidently dated prior to 1800.

Despite this apparent lack of early buildings, many of the older houses in Springfield have not yet been extensively researched, so it is possible that there might be at least a few 18th century homes still standing in the city. Most of the prominent colonial-era homes in Springfield were located along the Main Street corridor, which was heavily developed and redeveloped many times over the course of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. As a result, there are clearly no 18th century buildings still standing in the downtown area, but it is possible that some might still exist in the outlying areas, which experienced less development pressure over the years, and where individual buildings were not necessarily as well documented by past historians, who tended to focus on the downtown area.

There are several houses in particular that warrant further research, but perhaps the single strongest contender for the title of oldest building in the city is the house shown in these two photos, which stands at the northeast corner of Mill and Knox Streets. The early history of this house has not yet been fully traced, and the interior architecture does not appear to have been studied yet, but the exterior appearance of the house seems to suggest that it was constructed at some point in the second half of the 18th century. Important clues include the spacing of the windows, the steep roof, and the slightly overhanging second story, all of which were typical for houses of that period.

The earliest documented owner of this house is Ezekiel Keith, who was shown as living here on the 1835 map of Springfield. Keith was born in Canton, Massachusetts around 1778, but he was in Springfield by 1806 when he married Elizabeth Ashley. It is possible that this house was built around the time that they were married, but based on its architecture it seems more likely that it was built a few decades earlier.

The house remained in the Keith family throughout the first half of the 19th century. Elizabeth died in 1825, and four years later Ezekiel remarried to Mary Barber. He died in 1846, but Mary outlived him by many years and apparently lived in this house until her death in 1873.

During their many decades of ownership here, the Keith family would have seen many significant changes to the surrounding area. The house is located on a hill just a few hundred feet to the north of the Mill River, near where the modern-day Mill Street crosses the river. Ezekiel’ death records indicate that he had been a farmer, so it seems unclear as to whether he was involved in any of the manufacturing that occurred along the river, but during the first half of the 19th century this section of the river developed into an important industrial center.

The Mill River is the only major source of water power that is entirely in Springfield, so a number of factories were built along its banks, including the Armory Watershops, where much of the heavy manufacturing for the U.S. Armory occurred. The Watershops were originally located on three separate sites along the river, including the Middle Watershops, which were just a little further upstream from the Keith house. Downstream of the house, on the other side of Mill Street, were the Ames Paper Mills, which had been established by former Armory superintendent David Ames.

Census records prior to 1850 do not provide much information about exactly who was living in a particular house, but starting in 1850 the census recorded the names and demographic information of every household member. Here in this house, Mary Keith was living here with a large family. Two adult children from her first marriage, John Barber and Lucia Alden, lived here, as did her stepdaughter Olive Keith. The household also included Lucia’s husband Elijah Alden, and their children Lucia, Louisa, and Joel. Elijah worked as a carpenter, while John Barber was listed as being a gunsmith, probably at the nearby Armory Watershops.

After Mary’s death in 1873, her son John continued to live here. The 1880 census shows him here with his wife Harriet and a boarder, Dr. James W. Wicker. It seems unclear as to exactly what Dr. Wicker’s relationship to the Barbers was, but John died in 1887 and three years later Dr. Wicker married Harriet. He died in 1908, and Harriet died in 1916, ending about a century of ownership by the Keith/Barber families.

The house was subsequently owned by Walter and Otillie Cowles. They were living here by about 1918, and they initially rented the house before purchasing it in the early 1920s. During the 1920 census they were both in their early 40s, and they had five children: Augusta, Walter, Norman, Charles, and Irving. The elder Walter worked as a tile setter, while his 18-year-old son Walter was listed as a “tile helper,” presumably working with with his father. Their daughter Augusta was also employed, working as a machine operator in a toy factory.

The Cowles family was still living here when the top photo was taken in the late 1930s. By this point the house had undergone some exterior changes, likely after the Cowles family purchased it. These changes included a portico at the front entrance, a small addition on the right side of the house, and the installation of brick veneer on the first floor. Given Walter’s occupation as a tile setter, it seems plausible that he would have done the brickwork himself.

At some point the house was further altered by installing artificial siding on the upper parts of the house. This may have also occurred during the Cowles family’s ownership. Walter and Otillie lived here until their deaths in the 1960s, and the house remained in the family until 1990, when it was finally sold by Walter’s estate.

Today, the house is still easily recognizable from the first photo, and even the saw palmettos in the foreground appear to be some of the same ones that were here in the 1930s. At first glance, the age of this house is somewhat difficult to tell, since the exterior is entirely covered in 20th century materials. However, it is definitely one of the oldest surviving buildings in the city, and depending on its exact construction date it might be the city’s only surviving colonial-era building.