The Old Constitution House on North Main Street in Windsor, Vermont, around 1927. Image from The Birthplace of Vermont; a History of Windsor to 1781 (1927).

The scene in 2019:

Vermont is one of several states that was arguably an independent nation prior to statehood. Although never formally recognized by any foreign nation, the lightly populated, mountainous land between New Hampshire and New York was a de facto country between 1777, when it declared its independence, and 1791, when it voted to join the United States as the 14th state. Since then, Vermonters have retained a high degree of independence, particularly when it comes to political thinking. However, Vermont’s 1777 independence had less to do with lofty political ideals, and more to do with practical necessities.

Prior to the American Revolution, both New Hampshire and New York claimed the territory that would become Vermont, and both issued land grants to settlers here. These grants often conflicted with one another, leading to conflict between the two groups of settlers. The British government recognized New York’s claims, but a band of New Hampshire-affiliated settlers, led by Ethan Allen, formed the Green Mountain Boys in 1770 to protect their interests. Over the next few years this led to instances of violence, most notably the Westminster Massacre, when two protesters were killed by a New York-affiliated sheriff at the Westminster courthouse in March 1775.

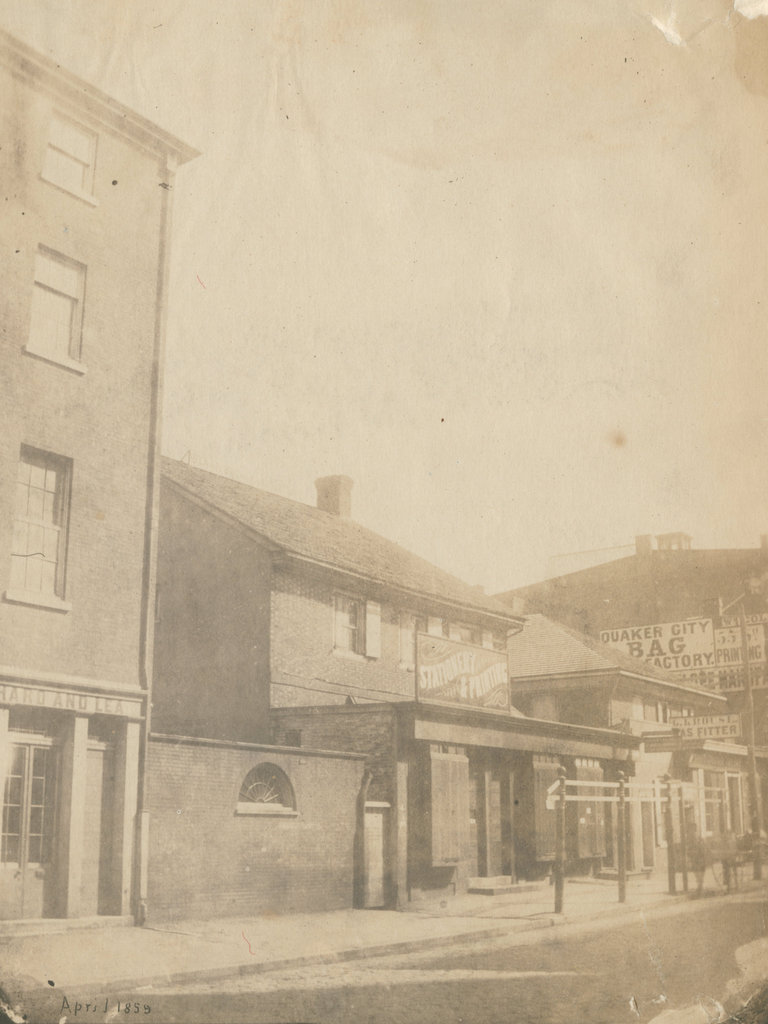

The settlers with New Hampshire grants ultimately gained control of much of the territory, and on January 15, 1777 they declared independence, at the same courthouse in Westminster where the massacre had occurred. In the declaration, the new state was named the Republic of New Connecticut, but several months later the name was changed to Vermont, which is based on the French name for the Green Mountains, les verts monts. From here, the next step was to draft a constitution to organize the new government. So, on July 2, 1777 the 72 delegates to the Vermont constitutional convention met here in Windsor, in the tavern of Elijah West. This building, which is shown in these two photos, was originally located on Main Street in the center of Windsor, although it has subsequently been moved twice over the years.

Unlike the United States Constitution, which took an entire summer to draft in 1787, the Vermont delegates created their constitution here in a week. They borrowed heavily from the Pennsylvania constitution, largely copying its structure and, in many cases, its exact wording. Among the features of the Vermont constitution was a declaration of rights, which guaranteed rights such as freedom of speech, freedom of religion, trial by jury, freedom from search and seizure, and free elections for all men in Vermont.

However, perhaps the most significant provision in the constitution’s declaration of rights—and one of the few not copied from Pennsylvania—was the first one, which abolished slavery among adults. This was the first constitution in the present-day United States to do so, although it proved difficult to enforce. Nonetheless, it was an important first step in ending slavery, and within less than a decade many other northeastern states had begun gradual abolition or, in the case of Massachusetts, outlawed it entirely.

The finished document was signed here in this building on July 8, 1777, and it went on to serve as Vermont’s constitution for much of the state’s time as a de facto independent nation. However, it was subsequently replaced by a new document in 1786, which was in turn followed by the current state constitution in 1793, two years after Vermont joined the union as the fourteenth state.

In the meantime, this building here in Windsor reverted to its primary use, and it remained a tavern until 1848. Then, around 1870 it was moved to a new location, where it was used first as a tenement house and then later as a warehouse. By the turn of the 20th century it was in danger of being demolished, but it was ultimately preserved and, in 1914, moved to its current location on North Main Street, just to the north of the village center.

The first photo was taken a little over a decade after the move. At the time, it was owned and operated as a museum by the Old Constitution House Association, which had been responsible for saving the building. Nearly a century later, very little has changed in this scene. The property was transferred to the state in 1961, but it continues to serve as a museum, and it stands as one of the oldest surviving buildings in Vermont. Because of its significance as the birthplace of Vermont, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971, and it is also a contributing property within the Windsor Village Historic District, which was established four years later.