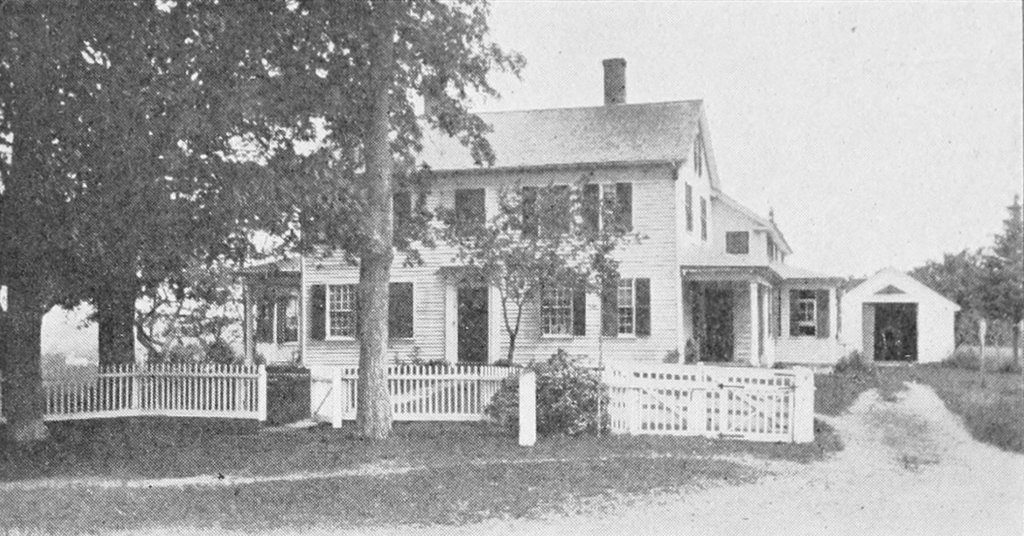

The house at 14 Mall Street in Salem, around 1910. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The house in 2017:

This house is best known as the place where Nathaniel Hawthorne lived from 1847 to 1850, and where he wrote The Scarlet Letter. However, the house predates Hawthorne’s time here by several decades. It was built in 1824, and was originally the home of Peter Edgerly, a teamster who had moved to Salem from his hometown of Gilmanton, New Hampshire. He purchased this house about two years after his marriage to his wife Vesta, and at the time he was involved in running a baggage wagon line in Salem. He and Vesta lived here for a decade, before selling the property in 1834, but he continued to live in Salem until his death in 1848.

Thirteen years after the Edgerlys sold this house, it became the home of Nathaniel Hawthorne and his family. A Salem native, Hawthorne was born in 1804 in a house on Union Street, just a little south of here. He spent much of his childhood in Salem, aside from a few years living with his uncles in Raymond, Maine, and subsequently attended Bowdoin College, where he graduated in 1825. His first novel, Fanshawe, was published anonymously three years later, and over the next decade his literary efforts consisted primarily of short stories that were published in magazines. These stories, which included the future classic “Young Goodman Brown,” gained little recognition at the time, although Hawthorne did enjoy some moderate success when these were republished in book form in 1837 as Twice-Told Tales.

In 1842, Hawthorne married Sophia Peabody, a member of the prominent Peabody family in Salem. After their marriage, they lived in the Old Manse in Concord, and they did not return to Salem until 1846, when Hawthorne was appointed Surveyor of the Port of Salem. This federal appointment earned him a salary of $1,200 per year, equivalent to about $33,000 today, and he found little enjoyment in the job, which distracted him from his writing. At first, he and Sophia rented a small house at 18 Chestnut Street, where they lived with their two young children. However, the house proved too small, and in 1847 they moved into this house at 14 Mall Street, along with Hawthorne’s mother and two sisters.

The cash-strapped Hawthorne had received his appointment to the Custom House thanks to his friendships with politically-prominent Democrats, including college classmate and future U.S. President Franklin Pierce. However, the same spoils system that had secured this position for Hawthorne would later cost him the job, after the Democrats lost the 1848 presidential election to Whig candidate Zachary Taylor. Hawthorne was dismissed from his position on June 8, 1849, just three months after Taylor’s inauguration, although in the long run this ultimately helped to advance his literary career, which had stagnated during his time at the Custom House.

Bitter over losing his job, and mourning the death of his mother in July, Hawthorne channeled his anger into his writing. From late summer of 1849 until February 1850, he wrote The Scarlet Letter here in this house, and it was published later that spring. The dark, bleak novel reflected his mood during this period, and Hawthorne evidently recognized as much. As he described in a February 1850 letter to his friend, Horatio Bridge, the novel “lacks sunshine. To tell you the truth it is . . . positively a h-ll-fired story, into which I found it almost impossible to throw any cheering light.”

The Scarlet Letter included a lengthy introduction, in which Hawthorne openly criticized both the Custom House and the city of Salem itself. This polemic – which addresses everything from the rotting wharves of a once-prosperous seaport, to the excessive eating habits of the Custom House inspector – has only the slightest connection to the plot of the novel, but it served as Hawthorne’s parting shot at his hometown. He also showed this frustration later in his letter to Bridges, writing:

I should like to give up the house which I now occupy, at the beginning of April; and must soon make a decision as to where I shall go. I long to get into the country; for my health, latterly, is not quite what it has been, for many years past. . . . I detest this town so much that I hate to go into the streets, or to have the people see me. Anywhere else, I shall at once be entirely another man.

Hawthorne soon followed through with this plan, and within a few months he and his family had moved across the state to Lenox in the Berkshires. The 1850 census shows him and Sophia living there with their daughter Una and son Julian, and the following year their family grew again with the birth of their youngest child, Rose. Hawthorne wrote two novels, The House of the Seven Gables and The Blithedale Romance, while in Lenox, but the family moved again in the fall of 1851, returning to Concord. Neither he nor Sophia would ever again live in their hometown of Salem, and Hawthorne died in 1864 while on vacation with Franklin Pierce in Plymouth, New Hampshire.

In the meantime, Hawthorne’s former house here on Mall Street has remained standing, nearly 170 years after he and his family moved out. Its historic and literary significance was already recognized by the time the first photo was taken around 1910, when it was photographed by the Detroit Publishing Company as part of their series of postcards showing notable Salem landmarks. Today, the house has seen few changes from this angle, although there are now skylights in the roof and the wing on the right side has been expanded. It is one of many historic homes that still stand on Mall Street and the other surrounding streets, and it is now part of the Salem Common Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.