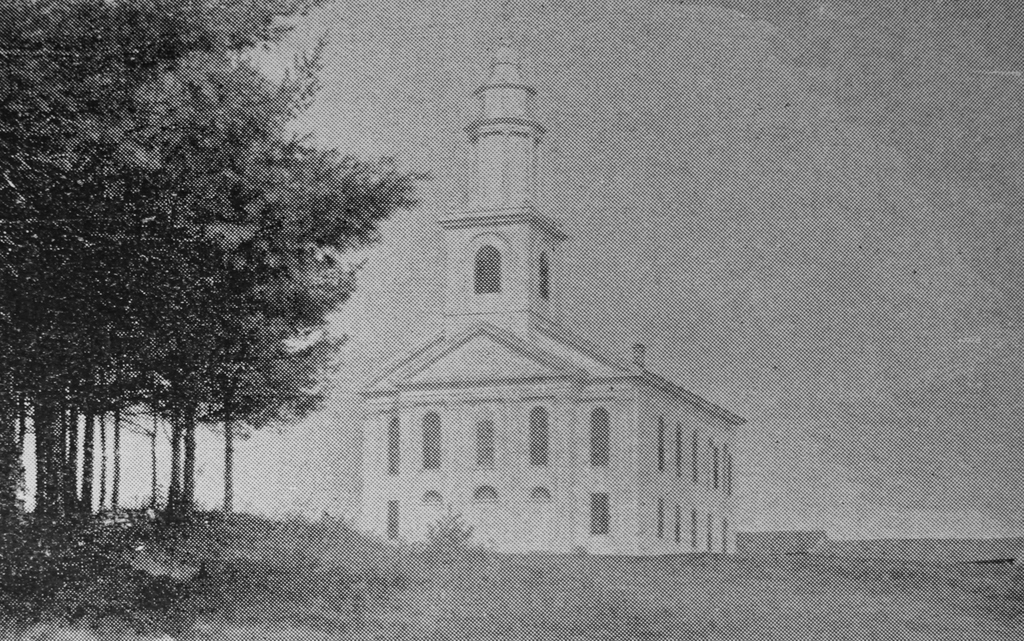

The original town center of Chester, Massachusetts, seen looking south on modern-day Skyline Trail from the corner of Bromley Road around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

The scene in 2024:

These two photos show the old town center of Chester, which was incorporated in 1765 and was originally named Murrayfield. Located in the far northwestern corner of Hampden County, Chester is one of the many hilltowns in the uplands region between the Connecticut River valley to the east and the Housatonic River valley to the west. Two of the branches of the Westfield River flow through Chester, with the West Branch in the western part of the town and the Middle Branch in the eastern section. The branches flow through narrow valleys, and in between them is a plateau of rolling hills.

It was this plateau that initially drew colonial settlers to Chester. The river valleys provided only a limited amount of potential farmland, but the hills were suitable for agriculture, particularly for raising livestock. As a result, the late 18th century development in the town was concentrated around this area on modern-day Skyline Trail, with this spot becoming the town center.

One of the first houses built here by colonists was the home of the town’s first pastor, the Reverend Aaron Bascom. Built in 1769, it is just out of view on the far right side of this scene, and it is still standing today, although it is vacant and badly deteriorated. The village here also included the town meetinghouse, along with a burial ground that is located in the distance on the left side of the road.

The population trends in Chester were consistent with what happened in many of the other hilltowns in this part of Western Massachusetts. It saw significant growth in the early 19th century, but subsequently declined in population as residents either moved west for better farmland or moved to industrial cities for greater opportunities. In Chester, the town’s population grew from 1,119 in 1790 to 1,542 in 1800, but it stagnated over the next few decades. The 1850 census marked the last time that the town ever recorded a population above 1,500, and since then it has generally fluctuated between about 1,000 and 1,400 residents.

Aside from the general decline in population during the mid-19th century, the town also saw changes in where people lived within the town. In 1841, the Western Railroad was built along the West Branch of the Westfield River. It passed through the southern and western parts of Chester, which helped to spur development in the river valley. This included the village of Chester Factories, which soon eclipsed the original town center here on what became known as Chester Hill.

The top photo was taken around 1892, showing the view looking south in the old town center. By this point the town’s population stood at about 1,300, and this was largely concentrated in the area around the railroad depot in the valley. Here on Chester Hill, the lack of population growth meant that things stayed essentially the same as they had been in the first half of the 19th century, with a handful of homes and other buildings clustered around the meeting house and burying ground.

The most prominent building in the top photo is the meetinghouse of the First Congregational Church. It was built in 1840, although it was constructed in part from timbers that had originally been used in the 1769 meetinghouse. It features a Greek Revival design, which was fashionable for church buildings of the period, and it was modeled after the meetinghouse in New Marlborough. As was often the case in small towns in Massachusetts at the time, it functioned as a house of worship but also as a space for town meetings, which were held in Chester Center through 1855, before the town meetings shifted to the settlement in the valley.

Across the street from the meetinghouse is the cemetery, with gravestones that date as far back as the 1760s. Next to the cemetery is the two-story district schoolhouse, which can be seen in the distance on the left side of the photo. It was built in 1796, and it was still in use as a school when the top photo was taken nearly a century later.

Aside from the meetinghouse and school, there are also two houses visible in the photo. On the far left side in the foreground is the Searle House, which was built in 1787 as the home of Zenas Searle. Across the street, on the far right side, is the Boies House, an elegant Federal-style house that was built in 1810 for the Rev. Bascom’s daughter Charlotte and her newlywed husband Dr. Anson Boies.

Today, more than 130 years after the top photo was taken, very little has changed in this scene, aside from the paved road in place of the dirt path. All four buildings are still standing with few alterations, and the village is a well-preserved example of a rural early 19th century town center. Along with the nearby Bascom House, these buildings are part of the Chester Center Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1988.