Memorial Hall on Main Street in Monson, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

The scene in 2020:

One of the most architecturally-impressive buildings in Monson is Memorial Hall, which was completed in 1885 as a town hall and a memorial to the town’s residents who served in the Civil War. Prior to this time, Monson did not have a purpose-built town hall; instead, town meetings were held at the First Church and the Methodist Church. It was at one of these town meetings, in 1883, that Rice M. Reynolds offered to donate land and money to help construct a new town hall. Together with his brother Theodore and their father, prominent local industrialist Joseph L. Reynolds, the family gave $17,000 towards the project, with the town covering the remaining $42,000 in construction costs.

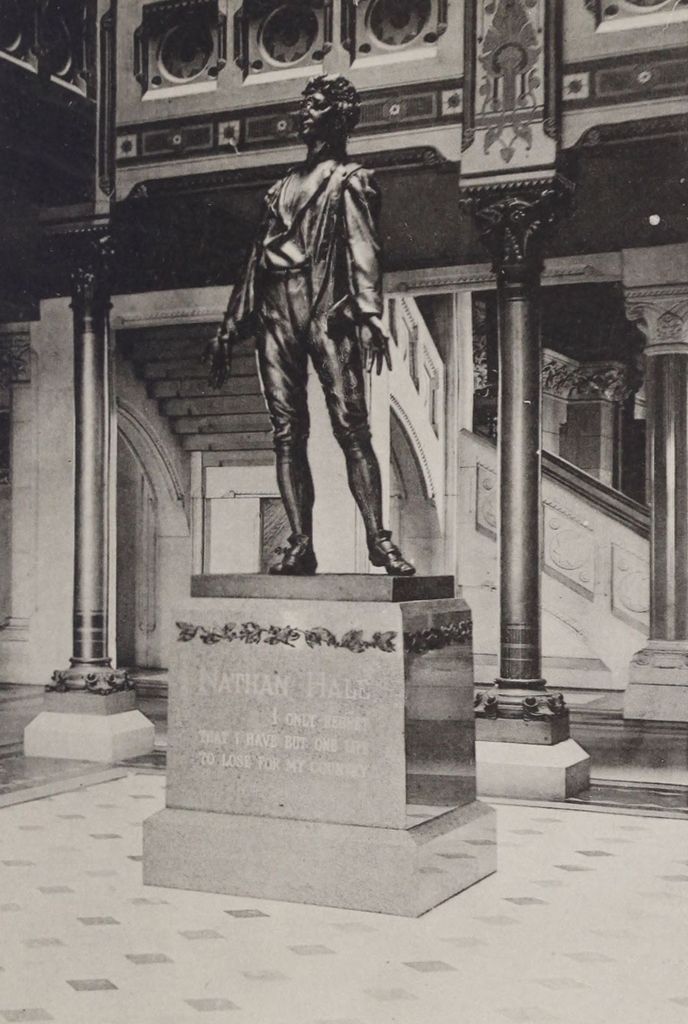

The late 19th century was the heyday for Civil War monuments in New England, and almost every city or town had at least one to recognize its residents who fought for the Union. Here in Monson, the town had two major memorials. The first of these was the Soldiers’ Monument in front of the First Church, which was donated by Cyrus W. Holmes and dedicated in 1884. Memorial Hall followed a year later, and together these two monuments honored the 155 Monson residents who served in the war. Of these, sixteen were killed in battle, and thirteen died of disease during the war.

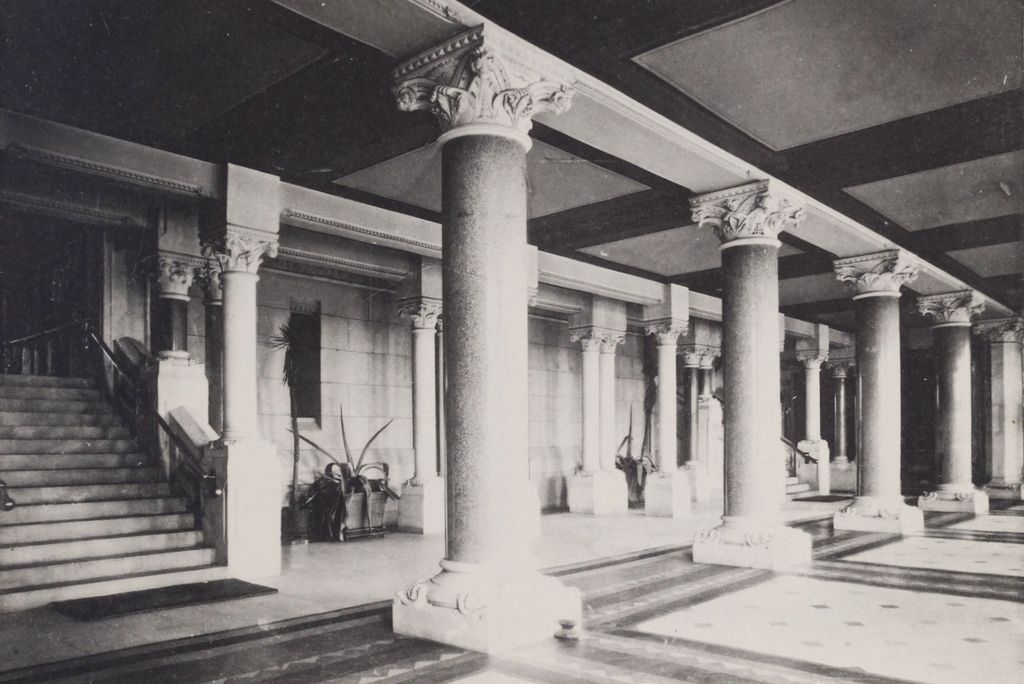

Memorial Hall was designed by architect George E. Potter, and it was constructed with granite that was quarried in the town by the William N. Flynt Granite Company. It features a Gothic-inspired design with an asymmetrical main facade. On the left side, at the northwest corner of the building, is a 100-foot tower, and on the right, in the southwest corner, is a 45-foot turret that is topped by a statue of a soldier. Most Gothic and Romanesque-style public buildings of this era were built with multi-colored exteriors, using either contrasting light and dark bricks or sandstone. This was not as easy to do with gray granite blocks, but there are were some efforts to create contrast, particularly with the alternating light and dark stones in the arches above the doors.

On the interior, the largest space in the building was the auditorium on the first floor. It had a capacity of a thousand people, and could be used for town meetings and other civic events. The building also included offices for town officials such as the town clerk, the selectmen, the assessor, and the superintendent of schools. In the basement was the town lockup, along with utility and storage space, including the town safe.

The second floor was originally occupied by the Marcus Keep Post of the Grand Army of the Republic. The GAR was a prominent and politically-powerful fraternal organization in the North during the late 19th century, and its membership was comprised exclusively of Union veterans of the Civil War. Here in Monson, the local chapter of the organization was named for Marcus Keep, a town resident who died from infection in 1864 after being wounded in the leg during a skirmish in Virginia. Along with the regular GAR post, the second floor space was also used by the Woman’s Relief Corps and the Sons of Veterans, the two main auxiliary organizations of the GAR.

Memorial Hall was completed in mid-1885, and the first public event to be held here was, appropriately enough, a service in memory of Ulysses S. Grant, who had died on July 23. Then, on August 15, the building was formally presented to the town at the first official town meeting here in Memorial Hall. The occasion was marked with little ceremony, and only about 50 voters attended the meeting. Rice M. Reynolds spoke on the reason for its construction, and then the chairman of the building committee, Edward D. Cushman, presented it to the voters, who accepted it.

The first photo was taken less than a decade after the building opened. Since then, remarkably little has changed here in this scene. Memorial Hall continued to be used as the town hall until 1992, when the town offices moved a few blocks north to the old high school building at the corner of Main and State Streets. The town still owns Memorial Hall, though, and it is now used for concerts, plays, fairs, and other community events.

As shown in the present-day photo, the exterior has remained well-preserved throughout this time, and even the 19th century homes on either side of it are still standing, although the one on the left was significantly expanded around 1910. Because of its historic and architectural significance, Memorial Hall was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984, and in 1991 it became a part of the Monson Center Historic District, which is also listed on the National Register.