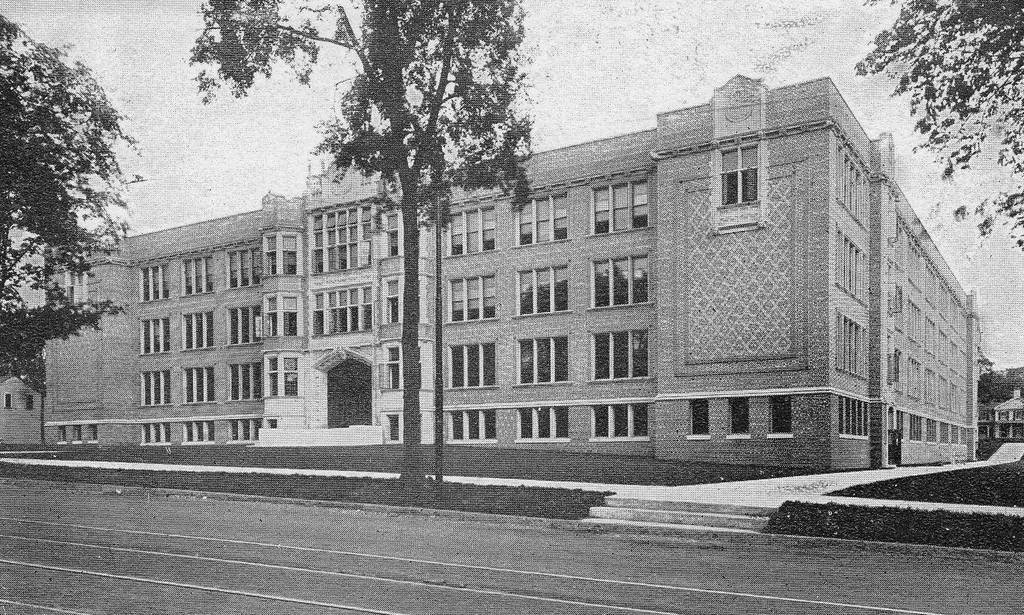

The house at 330 Park Drive in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The house in 2019:

This house is located in Colony Hills, an upscale residential neighborhood that was developed starting in the 1920s. The area is located just to the south of Forest Park, where it straddles the border of Springfield and Longmeadow. The Springfield side, where this house is located, is unusual in that it consists of two separate sections that are effectively enclaves of the city. They are surrounded on three sides by Forest Park, and on the fourth side by the Longmeadow border, so there is no direct road connection between Colony Hills and the rest of Springfield without passing through Longmeadow. As a result, the neighborhood is quiet and isolated from the rest of the city, making it a particularly desirable place to live.

About half of the houses on the Springfield side of the neighborhood are on Park Drive, which runs along part of the perimeter of Forest Park. Of these, this house has perhaps the most desirable location. The property lies in the center of a horseshoe-shaped curve, so it is almost entirely surrounded by wooded parkland, with no other homes visible from the front yard. The house itself was built in 1929, and it features a Tudor Revival design that was typical for upscale homes of this period. It was the work of Max Westhoff, a local architect who also designed similar homes on Maple Street and Longhill Street.

The original owner of this house was Daniel E. Burbank, a real estate investor whose properties included the Hotel Worthy in downtown Springfield. He ran a real estate business here in Springfield, but in 1932 he also became the real estate consultant for the Bickford’s restaurant chain, along with serving as one of the company’s directors.

Burbank was not living in this house during the 1930 census, but he and his family evidently moved in soon afterward. The first photo was taken sometime around the late 1930s, and the 1940 census shows Burbank living here with his wife Helen and their children Daniel Jr., Lyman, Barbara, and David. At the time, the house was valued at $50,000, or nearly $1 million today, and Burbank’s income was listed at over $5,000, which was the highest income level on the census.

Helen Burbank died in 1948, but Daniel continued to live here until his own death in 1960, at the age of 77. Later that year, the house was sold to Joseph J. Deliso, an industrialist who was, at the time, president and treasurer of the Hampden Brass & Aluminum Company, and president of the Hampden Pattern & Sales Company. Deliso has previously lived in a different Westhoff-designed house at 352 Longhill Street, and he went on to live here in this house on Park Drive for the rest of his life.

During this time, Deliso was instrumental in establishing Springfield Technical Community College after the closure of the Armory, and he was the first chairman of the STCC Advisory Board, serving from 1967 to 1981. He subsequently became the first chairman of the STCC Board of Trustees, and in 1992 one of the buildings on the campus was named Deliso Hall in his honor.

Deliso died in 1996, and a year later the house was sold to the Picknelly family, owners of the Peter Pan Bus Lines. The property is still owned by the Picknellys today, and the house remains well-preserved, with few exterior changes from this view aside from an addition on the far left side. It is now the centerpiece of the Colony Hills Local Historic District, which was established in 2016 and encompasses all of the historic homes on the Springfield side of the neighborhood.