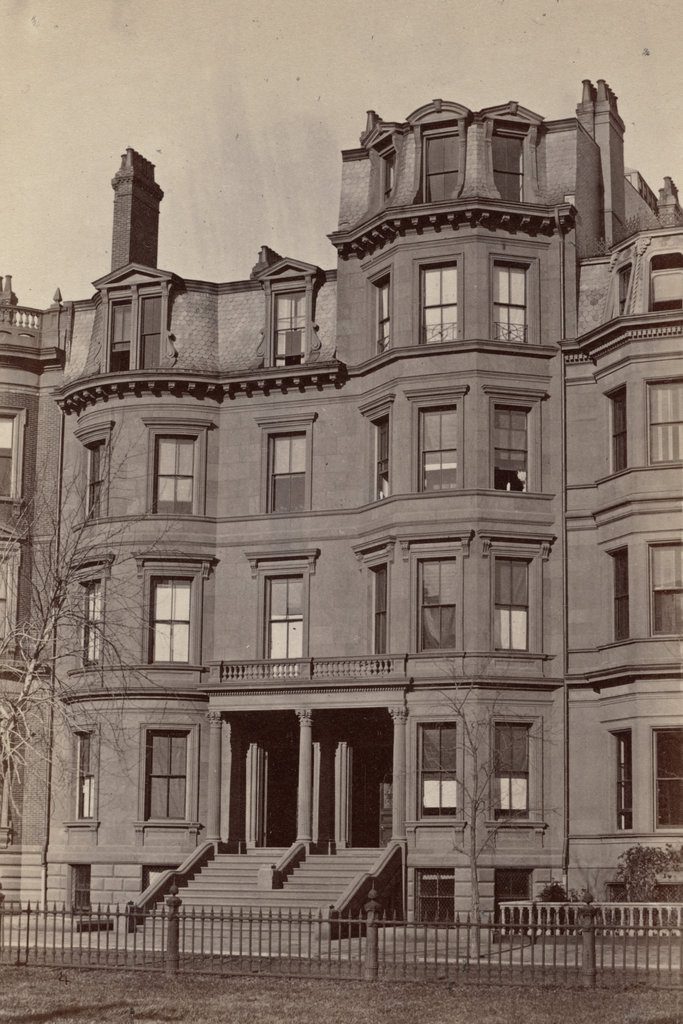

The houses at 7 and 9 Commonwealth Avenue in Boston, sometime in the 1870s. Image courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

The houses in 2017:

These two houses, built around 1861, were among the first in the city’s new Back Bay neighborhood. Like many other homes in the area, they were built as a symmetrical pair, with identical Second Empire-style architecture. The development of the Back Bay was intended to provide an upscale neighborhood for Boston’s upper class, in an effort to encourage them to remain in the city instead of leaving for the suburbs. The plan worked well, and many of the city’s wealthy residents soon made their way to new homes here, including dry goods merchants Richard Cranch Greenleaf and Samuel Johnson, Jr., who purchased these two properties.

Greenleaf lived in the house on the left at 9 Commonwealth, and Johnson lived in the one to the right, at 7 Commonwealth. Both men were partners in the C.F. Hovey department store, which was located on Summer Street in the present-day Downtown Crossing shopping district. The store was destroyed in the Great Boston Fire of 1872, but they soon rebuilt it, and the company remained in business until 1947, when it was purchased by Jordan Marsh. During this time, Richard Greenleaf and his wife Mary lived here with their son, Richard Jr., for a little less than a decade, before selling the house in 1870. However, Samuel Johnson and his wife, also named Mary, lived here for the rest of their lives, until her death in 1891 and his in 1898.

After the Greenleafs sold the house on the left, it was purchased by Otis and Lucy Norcross. A member of the prominent Norcross family, Otis was a merchant who imported crockery, pottery, glass, and earthenware. His company, Otis Norcross & Co., became one of the nation’s leading importers of such goods, and he also went on to have a successful political career, serving a term as the chairman of the board of alderman and another term as the mayor of Boston. He died in 1882, but Lucy continued to live here in this house until her death in 1916 at the age of 99, after having outlived five of her eight children.

One of the surviving Norcross children, their son Grenville, inherited 9 Commonwealth from his mother and owned it for the next two decades, until his death in 1937. That same year, the house was sold and converted into a 13-unit apartment building. The entire exterior was remodeled, and the original brownstone was replaced with light-colored stone on the lower third and brick on the upper two-thirds of the building. Along with this, two additional floors were added to the building to accommodate the new apartment units, and the front entrance was moved down to the ground floor.

In the meantime, 7 Commonwealth on the right side continued to be used as a single-family home for many years, with owners who included Mary Frothingham, the widow of former Lieutenant Governor and Congressman Louis A. Frothingham. She moved into this house in 1928, a few months after her husband’s death, and she lived here for more than 25 years, until her death in 1955. Like the house to the left, her house also became an apartment building, with 12 units, although the renovations were far less drastic than next door. The house would remain an apartment building for about 50 years, but in 2007 it was sold and converted back into a single-family home.

Today, 7 Commonwealth looks essentially the same as it did when the first photo was taken nearly 150 years ago, and 9 Commonwealth looks better than it used to. In 2013, it underwent another major renovation, which converted the 13 apartments into five condominiums. In the process, the 1930s exterior was replaced with a design that better matches its original appearance. Because of the two additional stories that had been added during the first renovation, the house is still not symmetrical with 7 Commonwealth, but today it is far more historically accurate than it had been for the previous 75 years.

For more detailed historical information on these houses, see the Back Bay Houses website for 7 and 9 Commonwealth.