The Emerson family plot at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, around 1900-1910. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2020:

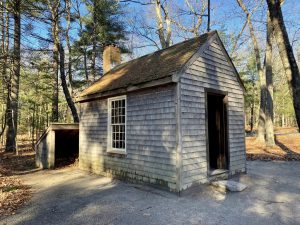

Ralph Waldo Emerson was one of the most important American philosophers of the 19th century. Born in Boston in 1803 to a family of Congregational pastors, he attended Harvard and briefly served as a pastor, but ultimately left the ministry following the death of his first wife Ellen. His beliefs subsequently shifted away from organized religion, and starting in the 1830s he began writing essays and delivering lectures that helped to establish the beliefs of Transcendentalism. Among Emerson’s most famous works were the essays “Nature” (1836) and “Self-Reliance” (1841), in which he outlines core Transcendentalist beliefs such as individualism, nonconformity, and an appreciation of the natural world. Emerson lived in Concord for most of his adult life, and the town became the center of this new philosophy, where he influenced other writers such as Bronson Alcott and Henry David Thoreau.

Transcendentalism coincided with the broader Romantic movement, which placed a greater emphasis on the natural environment than previous Western art movements. Although early 19th century Romanticism is primarily seen in artwork and literature, it also helped to inspire new ways of memorializing the dead here in New England. Prior to this time, most burials occurred in graveyards, which were typically open fields near village centers. In keeping with Puritan beliefs, these graveyards tended to be utilitarian in design, with little thought given to the aesthetics of the landscape. Even headstones were not always used, and the ones that were carved during the 17th and early 18th centuries tended to feature skulls and related imagery, in order to remind visitors of the inevitability of death.

In New England, these trends began to change during the early 19th century, particularly after the establishment of Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge and Watertown in 1831. The cemetery was laid out like a park, with attractive landscaping that featured winding paths, hills, ponds, and ornamental trees. This was the start of the rural cemetery movement, which focused on creating a tranquil, peaceful environment that would serve as both a final resting place for the dead and a pleasant park for the living.

By the second half of the 19th century, most cities—and many small towns—in the northeast had their own rural cemeteries, which were often modeled on Mount Auburn. Here in Concord, Sleepy Hollow Cemetery was established in 1855 on Bedford Street, just to the north of the town center. Rather than creating an artificial landscape, the cemetery was designed to incorporate the natural features of the site, including its hilly terrain and native plants and trees.

The design of the cemetery was very much in line with what the Transcendentalists believed about the importance of nature, and Ralph Waldo Emerson expressed this in his dedicatory address for the cemetery on September 29, 1855:

Modern taste has shown that there is no ornament, no architecture alone, so sumptuous as well disposed woods and waters, where art has been employed only to remove superfluities, and bring out the natural advantages. In cultivated grounds one sees the picturesque and opulent effect of the familiar shrubs, barberry, lilac, privet and thorns, when they are disposed in masses, and in large spaces. What work of man will compare with the plantation of a park? It dignifies life. It is a seat for friendship, counsel, taste and religion.

Later in the address, he spoke of nature in relation to the name “Sleepy Hollow,” which predated the cemetery by several decades:

This spot for twenty years has borne the name of Sleepy Hollow. Its seclusion from the village in its immediate neighborhood had made it to all the inhabitants an easy retreat on a Sabbath day, or a summer twilight, and it was inevitably chosen by them when the design of a new cemetery was broached, if it did not suggest the design, as the fit place for their final repose. In all the multitudes of woodlands and hillsides, which within a few years have been laid out with a similar design, I have not known one so fitly named. Sleepy Hollow. In this quiet valley, as in the palm of Nature’s hand, we shall sleep well when we have finished our day.

Finally, near the end of his address he offered a prediction for the future of this cemetery:

But we must look forward also, and make ourselves a thousand years old; and when these acorns, that are falling at our feet, are oaks overshadowing our children in a remote century, this mute green bank will be full of history: the good, the wise and great will have left their names and virtues on the trees; heroes, poets, beauties, sanctities, benefactors, will have made the air timeable and articulate.

More than 165 years have passed since Emerson presented this speech, and we are certainly in “a remote century” by comparison to his time. In many ways, his predictions have held true, and Sleepy Hollow Cemetery certainly has its share of “the good, the wise and great” who are buried here. Appropriately enough, Ralph Waldo Emerson is among them. He died in 1882 at the age of 78, and is buried here on a hill in the back of the cemetery, which is known as Author’s Ridge. This is the final resting place not only for Emerson but also for some of the nation’s greatest writers of the 19th century, including Louisa May Alcott, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry David Thoreau.

Emerson’s gravestone, shown here in the center of these two photos, is a massive uncarved rose quartz stone. This seems only fitting for Emerson who, as he indicated in his dedicatory address, preferred natural beauty over manmade ornamentation. He is buried here alongside his second wife Lidian, who died in 1892. She is buried just to the left of his gravestone, and on his right is their daughter Ellen. She died in 1909, and her gravestone is not here in the first photo, which suggests that the photo was taken before her death, although it is also possible that the gravestone was placed here several years later.

Today, aside from the addition of Ellen’s gravestone and several others, not much has changed here in this scene. Sleepy Hollow Cemetery remains an active cemetery, with much of the same natural beauty that its 19th century founders had envisioned. It is also a popular destination for visitors to Concord, who come here to pay their respects to Emerson and the “heroes, poets, beauties, sanctities, benefactors” and other prominent individuals who are buried here.