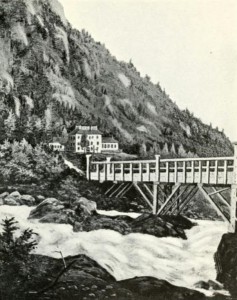

The Tucker Toll Bridge over the Connecticut River at Bellows Falls, Vermont, around 1900-1910. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2014:

As mentioned in this post, Bellows Falls became a major transportation and industrial center in the region during the 19th century because of its location on the Connecticut River. As seen in these photos, the river drops 52 feet in elevation through a narrow gorge, making it an ideal site for hydroelectrically-powered industries, but also a strategic location to build a bridge. Further south, the river was much wider and bridge-building viewed as almost impossible; one man reportedly commented on the idea in Springfield, Mass. around 1800, saying, “Gentlemen, you might as well undertake to bridge the Atlantic Ocean.”

However, here in Bellows Falls the width of the river and the rocky outcroppings meant a shorter bridge and no need to build piers in the river. As a result, the first bridge across any part of the Connecticut River opened on this spot in 1785, connecting New Hampshire and Vermont and facilitating trade from New Hampshire to Montreal and other northern destinations. At the time, Vermont was actually an independent nation, which I suppose technically made the first bridge an international border crossing.

The construction of the bridge was authorized by the state of New Hampshire, who also set the tolls for travelers; in 1804, the tolls ranged from three cents for a person on foot, to 30 cents for a four wheel carriage with four horses. Upon completion, the Massachusetts Spy gave a glowing review of the bridge, writing:

“We hear from Walpole, state of New Hampshire, that Colonel Enoch Hale hath erected a bridge across the Connecticut River on the Great Falls, at his own expense. This bridge is thought to exceed any ever built in America in strength, elegance, and public utility, as it is the direct way from Boston through New Hampshire and Vermont to Canada, and will exceedingly accommodate the public travel to almost any part of the state of Vermont.”

The 1907 book History of the Town of Rockingham Vermont provides this depiction of the bridge, viewed from about the same spot as the two photographs:

This first bridge was uncovered, which meant the wood deck and structure was exposed to the elements, so by 1840 it was in need of replacement. The new bridge, which is the same one in the first photo here, was built directly over the old one, about 15 feet above it, which allowed the old bridge to continue to be used even as its replacement was being built. The 1840 bridge became known as the Tucker Toll Bridge, named after the family who owned it for many years. It remained in the hands of private owners until 1904, when the towns of Rockingham and Walpole purchased it and made it free for travel. This bridge was, in turn, replaced by the current concrete arch bridge in 1930. However, it has deteriorated over the years, and was closed in 2009 because of safety concerns. At this point, it remains to be seen what will happen to the bridge.