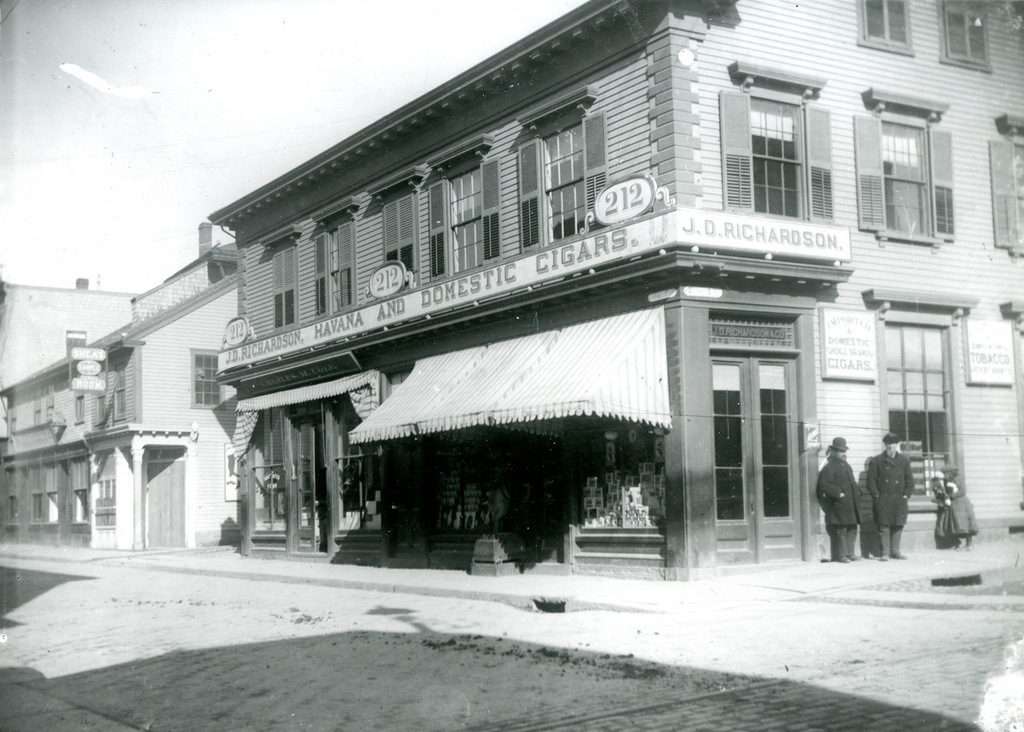

The northeast corner of Thames and Franklin Streets in Newport, around 1885. Image courtesy of the Providence Public Library.

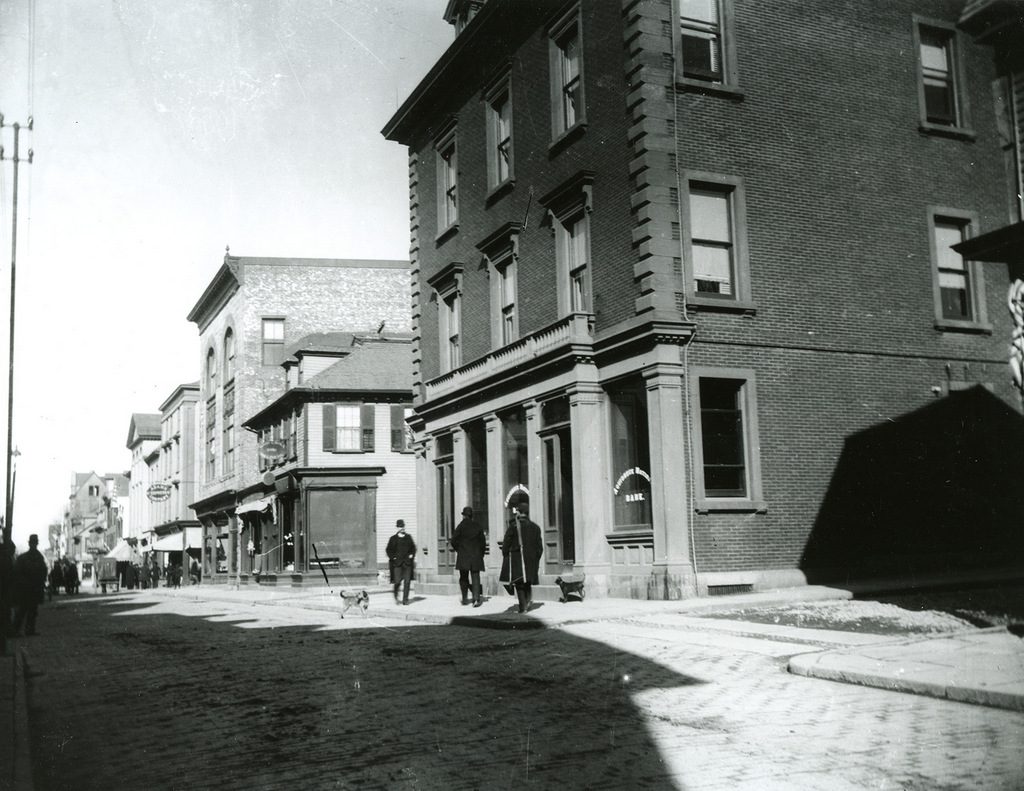

The building in 2017:

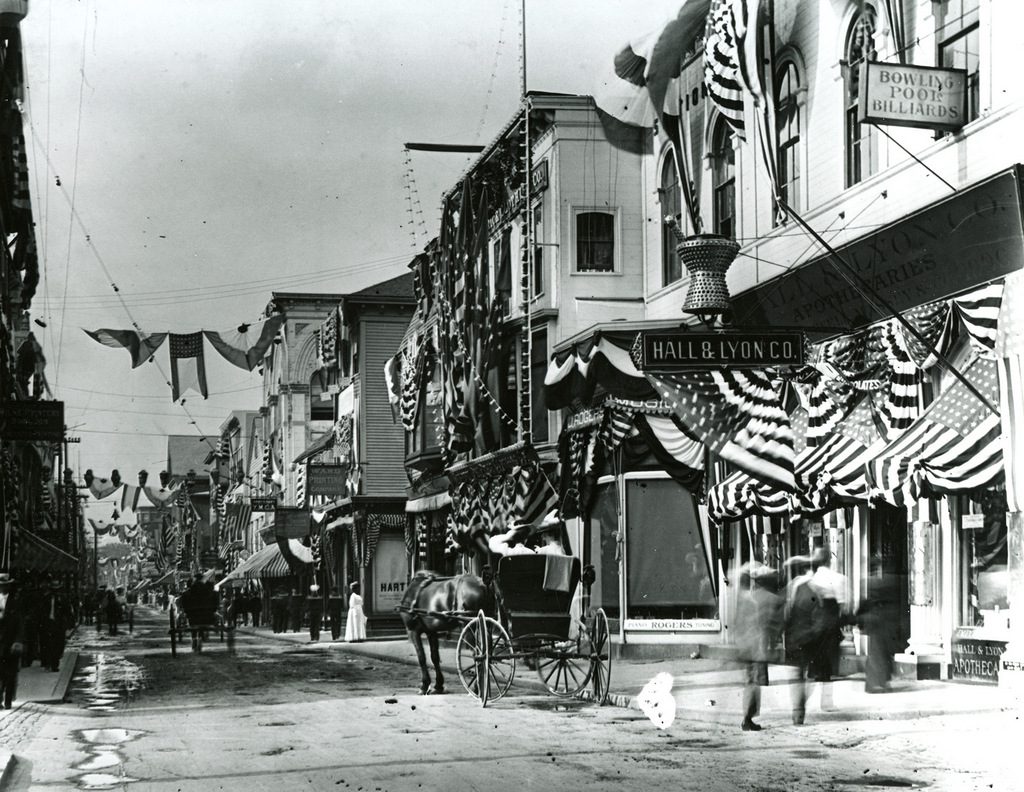

Newport has many fine examples of architecture from a wide variety of styles, ranging from the colonial era to the 20th century. However, there are comparatively few examples of Federal-style architecture, which was common throughout the northeast in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. This era coincided with a stagnation in Newport’s economy, which lasted from the American Revolution until the 1830s, when the city started to become a popular resort community. As a result, there was a limited amount of new construction, and none of Newport’s great architectural landmarks date to this period.

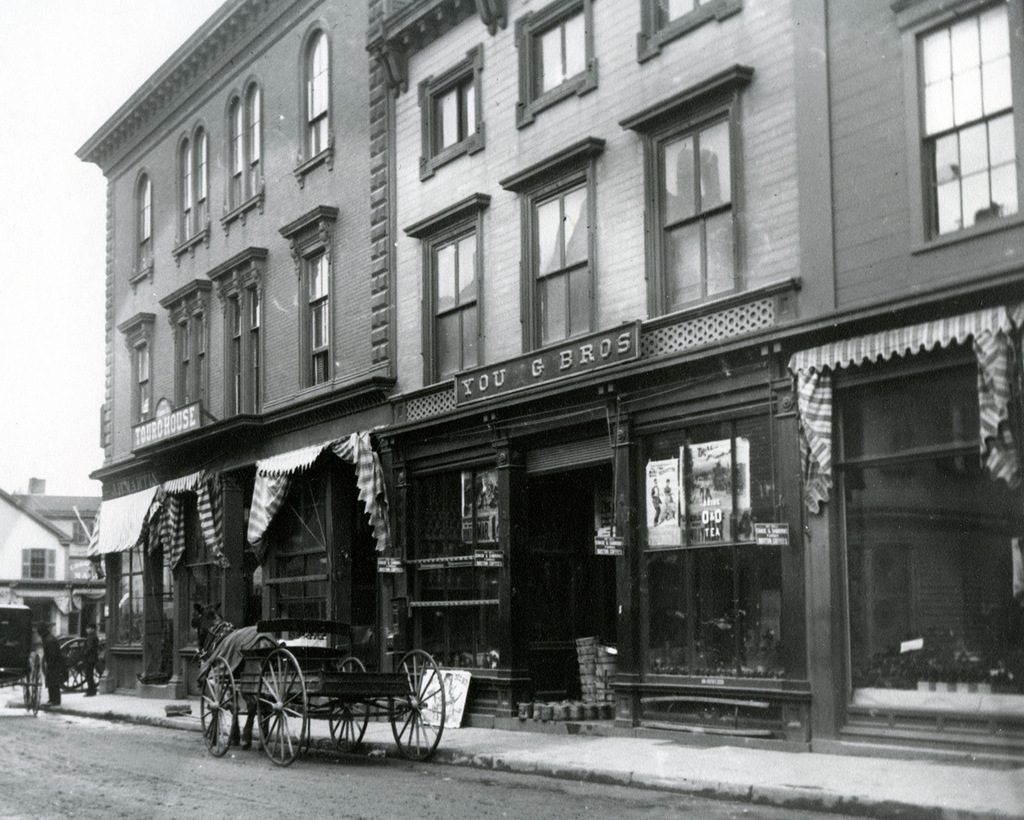

This modest commercial block, located at the corner of Thames and Franklin Streets, was built toward the end of this period, with the National Register of Historic Places inventory listing it as having been built in 1827 by Benjamin James. The early history of the building seems unclear, but by 1860 the ground floor was the home of William Alderson & Co., a wholesale tobacco and alcohol store. An 1860 advertisement in the Newport Daily News listed a wide variety of tobacco, pipes, cigar cases, snuff boxes, and related merchandise. In addition, the advertisement listed “Fine old Wines, Champagnes, Syrups, Cordials, Bitters, &c., fine old Brandies, Hollands, Gin, Wolfe’s Genuine Aromatic Schiedam Schnapps, and Liquors generally.” They were also “Agents for the Columbian Brewery Co.’s Pale and Amber Ale and Porter,” and offered “Goods delivered to any part of the city free of expense.”

By the end of the 1860s, the tobacco shop here was owned by John D. Richardson, “dealer in Havana and domestic cigars, fine meerschaum and briar pipes, tobacco, snuff, and smokers’ articles of all descriptions,” as listed in the 1869 city directory. Richardson was in his late 30s at the time, and during the 1870 census he and his wife Abby were living in an apartment above the store, along with their 12-year-old son John, Jr. According to that same census, Richardson did not own any real estate, but he had a personal estate valued at $2,000, equal to nearly $40,000 today.

The Richardson’s later moved into their own house at some point in the 1870s, but John was still running his business here in this building on Thames Street when the first photo was taken around 1885. The photo also shows a drugstore here in this building, in the storefront on the left side. Opened in 1885 by Charles M. Cole, the store sold “Drugs and medicines, a complete assortment of hair, tooth and nail brushes, perfumes, soaps, etc.,” as indicated in that year’s city directory. Like Richardson had previously done, Cole also lived in an apartment above the store, although by 1890 he and his wife Ella were living in a house elsewhere in Newport, along with their young son Norman.

John D. Richardson died in 1891, but his family remained in the cigar business for many years. The firm later became Richardson & Tilley, and operated out of this building until at least 1929, the last year that the company appears in the city directory. Cole, however, remained in business in this building for nearly 50 years, running his drugstore in the storefront on the left side until his retirement in 1933, two years before his death at the age of 77. In an article about his retirement, the Newport Mercury and Weekly News noted that “In all the years the structure has remained with no alteration, except a front installed by Mr. Cole some years ago, the old paneling and ornamentation remaining in its original form.”

Today, more than 130 years after the first photo was taken, the building’s exterior still has not significantly changed. There have been some minor changes, such as a large window on the right side, and the some of the old details, such as the window lintels, have been removed. The drugstore and the cigar shop are long gone, but the building itself still stands well-preserved, and it is now part of Newport Historic District, a National Historic Landmark district that was established in 1968 in downtown Newport.