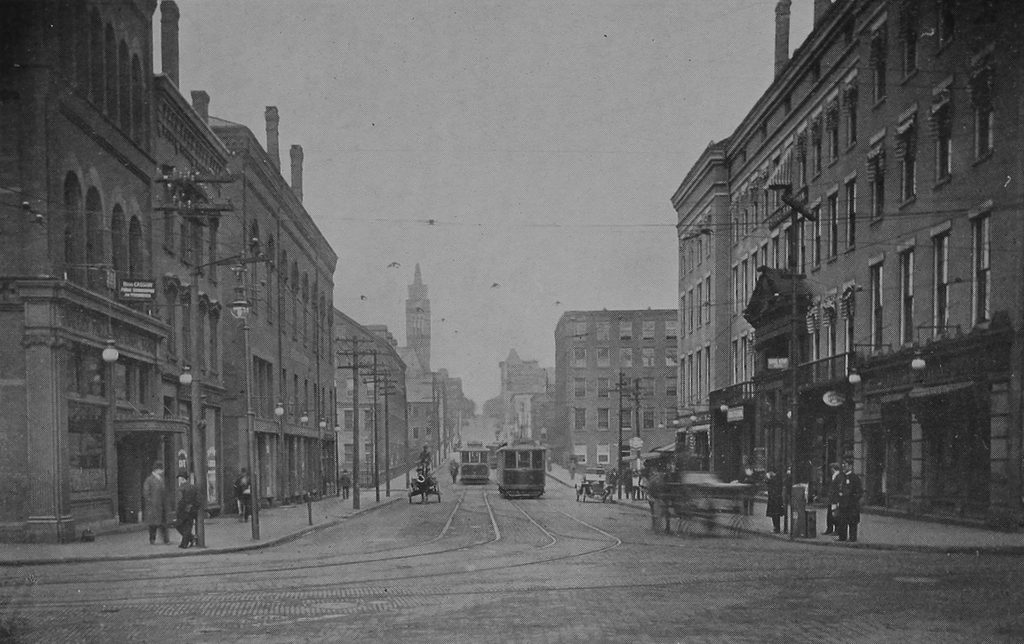

The old Union Station in Springfield, seen from near the corner of Lyman and Chestnut Streets around 1900-1910. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2018:

The first photo shows Union Station as it appeared about 10 to 20 years after its completion, as seen looking west from near Chestnut Street. The photo in a previous post shows the south side of the station from Lyman Street, but this view provides a more elevated look at the station, showing both the north and south sides, along with the platforms in between. Further in the distance, beyond the station on Main Street, are two of the city’s leading hotels: the Massasoit House on the far left at the end of Lyman Street, and Cooley’s Hotel, which can be seen in the center of the photo.

This area has been the site of Springfield’s primary railroad station since 1839, when the Western Railroad arrived, linking Springfield with Worcester and Boston. The original station, which was located on the west side of Main Street, burned in 1851, and the following year it was replaced by a brick and iron, shed-like station on the same spot. This station served for most of the second half of the 19th century, but it began to cause problems as the city grew in population and as rail traffic increased. Because the station was located at street level, trains had to cross directly over Main Street, leading to significant delays for traffic on the street. The station itself was also becoming insufficient for the number of trains that passed through here, and by the late 1860s there were already calls for a new station and elevated tracks through downtown Springfield.

In 1869, the state legislature authorized such a project, but it would take another 20 years before it was actually finished, thanks to an impasse between the city government and the Boston & Albany Railroad, which was the successor to the old Western Railroad. This dispute centered around which side was responsible for paying to raise the tracks and lower the grade of Main Street, and it ultimately did not get resolved until 1888, when the railroad agreed to spend around $200,000 to raise the tracks, while the city would spend about $84,000 to lower Main Street by four feet.

This compromise enabled the station project to move forward, and the old station was demolished in the spring of 1889. The new one was completed in July, and it was located on the east side of Main Street, which provided more room for the station. It featured a Romanesque Revival-style design, and the original plans had been the work of noted architect Henry H. Richardson, who designed many of the stations along the Boston & Albany Railroad. He died in 1886, though, and his successor firm of Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge subsequently modified the plans for the Springfield station.

One of these changes proved to be a serious design flaw. Richardson had intended for a single station building, located on the south side, with a large train shed over the tracks. However, the Connecticut River Railroad, which would share the union station with the Boston & Albany and the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroads, objected to this plan, wanting a separate building on the north side. As a result, the finished station consisted of two buildings, each with its own ticket offices and waiting rooms, and four tracks in between them. The smaller northern building, on the right side of this scene, served northbound and westbound travelers, while the larger building on the south side was for those heading southbound and eastbound.

Within less than 20 years, this design was already causing problems as Springfield continued to grow. Having two different station buildings was an inefficient use of space, since it meant redundant facilities such as the waiting rooms. This was also a source of confusion for passengers, who would sometimes find themselves at the wrong ticket office or platform. In addition, the two buildings prevented the railroads from adding new tracks, since the space in between was already filled with four tracks and three platforms.

Aside from practical considerations, the architecture of the building was also obsolete by the early 20th century. Romanesque Revival had been widely popular during the last two decades of the 19th century, particularly for public buildings, and railroad stations were seen as important architectural showcases. They were usually the first thing that a traveler saw in a particular city, so any self-respecting city need a monumental station, in order to give a good first impression to visitors. This may have been the case for Union Station in the 1890s, but Romanesque Revival had fallen out of favor by the next decade, and the new generation of iconic railroad stations – such as Grand Central and Penn Station – began to feature classically-inspired Beaux-Arts designs.

As early as 1906, it was evident that the station was inadequate. That year, the Springfield Republican published an article on the city’s numerous railroad-related problems, observing that “[t]he most important problem as far as the safety and convenience of the public is concerned is the rebuilding of the union station.” In 1921, the newspaper was even more explicit, remarking on how “there seems to be, in fact, a nearly unanimous demand that the structure be cast to the scrapheap,” and four years later it declared that the station was “long execrated for its combination of discomfort, dinginess and danger.”

The station’s demise was hastened by a November 1922 fire that caused about $25,000 in damage to the north building. The fire was considered to be suspicious, but its origins were unclear, with the railroad superintendent simply telling the Republican, “your guess is as good as mine.” The city’s fire chief declared that he found no evidence of arson, although he did not actually inspect the cellar beneath the waiting room, where the fire had apparently started. There were no injuries, and most of the valuables, including mail, packages, and cash, were safely removed by railroad employees and by an off-duty police officer.

Within less than a month of the fire, the railroad had approved the plans for a new station. This replacement would be in approximately the same location, but the entire station would be located on the north side of the tracks. It would be connected to Lyman Street on the south side by way of a tunnel beneath the tracks, and this tunnel would also provide access to the platforms, avoiding the dangers of passengers crossing directly over the busy tracks. Perhaps most significantly, the number of tracks would be increased from four to 11, reducing congestion and delays on the railroad.

Demolition on the old station began in 1925, just 36 years after it was built, and the new Union Station opened the following year. It would remain in use for the next few decades, but passenger rail began to experience a significant decline throughout the country during the post-World War II era. With passenger trains becoming unprofitable for railroads to operate, Amtrak ultimately took control of the country’s passenger rail services in 1971. Two years later, most of Union Station was closed except for the Lyman Street entrance, and a small Amtrak station was built on the south side of the tracks.

Union Station sat empty for many years, and only one of the old station platforms was used for passenger service. However, the building underwent a major restoration in the 2010s, reopening in 2017. It now features a ticket office, waiting area, and retail space in the concourse, along with office space on the upper levels, including the offices of the Peter Pan Bus Lines. Union Station is also the terminus for most of the city’s PVTA bus lines, with 18 bus berths just to the west of the station. In addition to this, the rail traffic here at the station has also increased. Along with a number of daily Amtrak trains, Union Station is also served by the Hartford Line, which opened in 2018 with commuter trains running from Springfield south to New Haven.

The 2018 photo shows this scene about a year after the station reopened. An Amtrak train is visible in the distant center of the photo, consisting of two passenger cars pulled by a P42DC diesel engine. This is the typical setup for most of the Springfield to New Haven Amtrak trains, and the rear car is a converted Metroliner cab car, which allows the train to be operated in either direction without turning the locomotive. Just to the right of the train is Platform C, which was the last part of the station’s renovation project. It was still unfinished when the first photo was taken, but this project – which upgraded the platform to modern accessibility requirements – was finished in January 2020, marking the end of Union Station’s restoration.