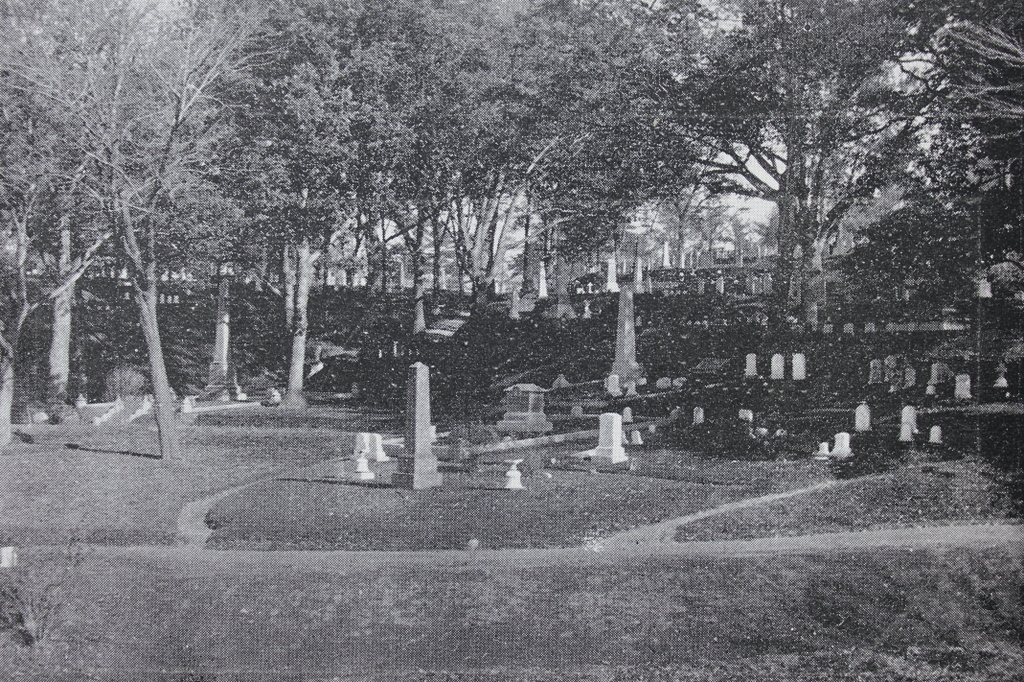

The Pynchon family plot in Springfield Cemetery, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

The scene in 2020:

Springfield Cemetery was established in 1841, but it includes the remains of many of Springfield’s earliest colonial settlers, dating back to the mid-1600s. Originally, these residents were buried in a graveyard in downtown Springfield, on Elm Street between Old First Church and the Connecticut River. However, by the 1840s that land had become valuable real estate in the center of a growing town, and part of the graveyard was in the path of a new railroad along the river. Because of this, in 1848 the remains were exhumed, and nearly all were reinterred in Springfield Cemetery.

A total of 2,434 bodies were removed from the old graveyard, along with 517 gravestones. Friends and family members of the deceased had the option of having the remains buried in a different cemetery, or in a private lot here in Springfield Cemetery, but most were interred along the Pine Street side of the cemetery. Those bodies accompanied by gravestones were buried beneath their respective stones, and the hundreds of unidentified remains with no gravestones were buried in an adjacent lot.

Among those buried in private lots were members of the Pynchon family. The Pynchons were probably the most influential family in the early years of Springfield’s history, in particular the family patriarch, William Pynchon, who founded the settlement in 1636. He returned to England in 1652 after the publication of his controversial book, which the Puritan leaders found heretical, so he was not buried in Springfield. However, his children stayed here in Springfield, where they would play an important role in the town throughout the rest of the 17th century.

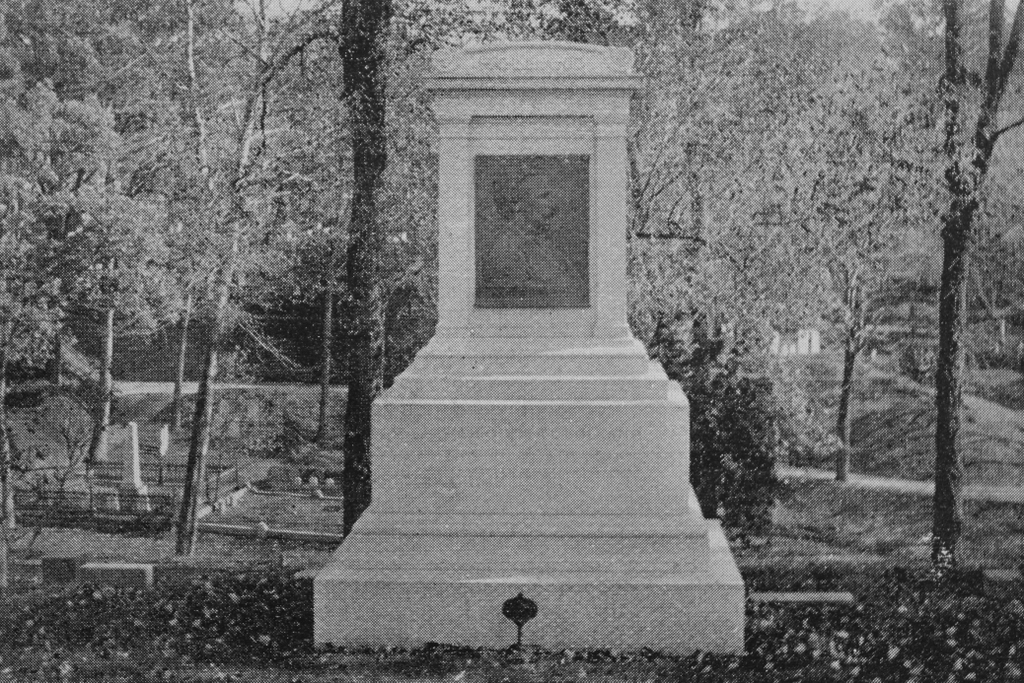

One of William Pynchon’s children was his daughter Mary, who came to Springfield as a teenager in the 1630s and married Elizur Holyoke in 1640. She died in 1657, and her gravestone is the oldest surviving stone here in the cemetery. It is visible on the left side of this scene, just behind and to the left of the large monument in the center of the photos. Gravestones were uncommon in New England before the late 1600s, as early burials were typically marked by simple fieldstones or wooden markers, if at all. Few gravestones in the region are dated prior to the 1660s, and many of these were likely carved years or decades after the fact. It is possible that Mary’s gravestone was carved at a later date, but either way it is definitely very old and was likely carved at some point in the 1600s.

Aside from its age, Mary Pynchon Holyoke’s gravestone is also memorable for its epitaph, which reads:

Shee yt lyes here was while she stood

A very glory of womanhood

Even here was sown most pretious dust

Which surely shall rise with the just

When her body was disinterred from the old burying ground in the spring of 1848, the remains of two different people were found beneath this stone. Writing several decades later in 1885, in Record of the Pynchon Family in England and America, Dr. J. C. Pynchon speculated that the second body may have been Elizur Holyoke, although there is no known record of where he was buried. In any case, there was little left of either body, with Pynchon writing:

These remains were found side by side, in the white sand, about six feet below the surface. This sand was discolored, and some few pieces of the skulls and other bones were found, while even the screws or nails of the coffins were wholly destroyed, their places being marked by the rust only, while no other vestige of the coffins remained. The few remains were gathered, which soon crumbled to dust on exposure to the air, and, with the surrounding earth, deposited in the new cemetery, after having lain in the old burying ground, in the case of Mary Holyoke, one hundred and ninety-one years.

Aside from Mary’s gravestone, the Pynchon family lot here also includes the large monument in the center of the scene. As indicated by the inscription here on this side of it, the monument was “Erected under a provision in the will of Edward Pynchon, who died Mar. 17, 1830. Æ 55.” Edward Pynchon was the 4th great grandson of William Pynchon, and he held a number of local political offices, including town clerk, town treasurer, county treasurer, and county register of deeds. In his will, he noted that the old Pynchon family monument had fallen into disrepair, and instructed his executors to install a new monument on the same spot in the old burying ground, with inscriptions for the family members buried there. This was carried out after his death, and then in the late 1840s this monument was moved here to this lot in Springfield Cemetery, presumably accompanied by the remains of the Pynchons who were buried beneath it.

The monument is carved of sandstone, which was the most common gravestone material in the Connecticut River Valley during the 17th, 18th, and early 19th centuries. However, sandstone does not always weather very well, and many of the inscriptions on the Pynchon monument have been eroded away, particularly here on the west side, where the entire panel has been obliterated. Although much of the monument is now illegible, the Springfield Republican published a transcription of it in 1911, along with the location of each name:

(East side over panel):— Hon. John Pynchon died Jan 17 1702, Æ 76, Amy his wife died Jan 9 1698 Æ 74

(South end): Hon John Pynchon died Apr 25 1721 Æ 74, Margaret his wife died Nov 11, 1746

(On north end): John Pynchon 3d Esq. died July 12, 1742 Æ 68. Bathshua his wife died June 20 1710 Æ 27; Phebe his wife dwho died Oct 10 1722 Æ 36; John Pynchon his son died Apr 6 1754 Æ 49.

(On west side over panel): Erected under a provision in the will of Edward Pynchon who died Mar 17 1830 Æ 55.

(On west side in panel, probably a continuation of north end): Bathshua his daughter & wife of Lieut Robert Harris died 1760 Æ 52.

William Pynchon Eqs. son of Hon John Pynchon 2d died Jan 1741 Æ 52; Catharine his wife died Apr 10 1747 Æ 47; Sarah their daughter wife of Josiah Dwight Esq died Aug 4 1755 Æ 34. Edward Pynchon Esq son of John Pynchon 3d died Jan 11 1783, Æ 80.

(On west side under panel) Susan wife of Edward Pynchon died Oct 15 1872 Æ 82.

(East side panel) Sarah relict of William Pynchon Esq died Feb 21 1796 Æ 84.

Elizabeth relict of Benjamin Colton daughter of John Pynchon 3d Esq died Sept 26 1776 Æ 74; Capt George Pynchon son of John Pynchon 3d died June 26 1797 Æ 81; Maj William Pynchon died Mar 24 1808 Æ 69; Lucy his wife died Feb 17 1814 Æ 75; John Pynchon died Mar. 1826 Æ 84.

The first photo was taken a little over 40 years after the gravestones were moved here to Springfield Cemetery. Since then, there have been a few small changes, such as the deterioration of the inscriptions on the Pynchon monument. Along with this, there are now newer gravestones in this section of the cemetery, and several of the 19th century gravestones appear to have been removed or replaced, including the one in the lower foreground of the first photo. This one might still be here, as there is a mostly-buried gravestone in the same location today, but its lettering is mostly illegible. Overall, though, despite these changes this scene still looks much the same as it did more than 125 years ago, and Springfield Cemetery retains its appearance as a rural cemetery in the midst of a large city.