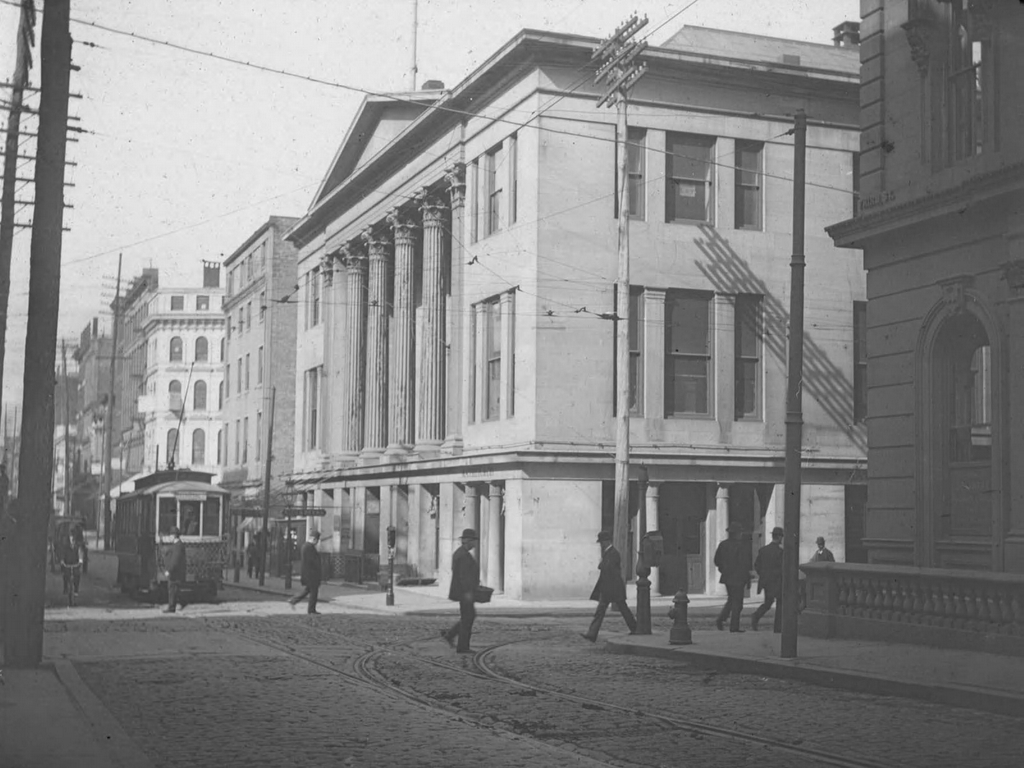

The house at 81 Essex Street, at the corner of Orange Street in Salem, around 1890-1914. Image courtesy of the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum, Frank Cousins Collection of Glass Plate Negatives.

The house in 2019:

The second half of the 18th century was a time of great prosperity for Salem because of its thriving maritime trade, and many of the town’s wealthy captains and merchants built fine houses such as this one. This house was built around 1750 by John Hodges, a ship captain who was about 26 years old at the time. Hodges had purchased this property a year earlier, the same year that he married Mary Manning. The couple subsequently raised eleven children here, four of whom died young. Of the surviving sons, five went on to become captains themselves, although two of them died at sea.

Their third child, Benjamin, became one of Salem’s leading captains in the late 18th century. He was a cousin of Elias Hasket Derby, one of the richest merchants in New England, and he frequently commanded Derby’s ships, including the Grand Turk and the Astrea, which were among the first American ships to trade with the far east. Later in his career, Benjamin Hodges was involved in the construction of the frigate USS Essex, the largest ship—and only warship—ever built in Salem. It was funded by subscription from residents of Salem, including Hodges, who also served on the building committee, and it was presented to the United States Navy in 1799. Also in 1799, Hodges was one of the founders of the East India Marine Society, which has since become the Peabody Essex Museum. He then became the organization’s first president, serving until his death in 1806.

Benjamin Hodges acquired this house from his father in 1788, and he lived here with his wife Hannah and their large family. Tragically, though, most of their children died young from tuberculosis, starting with an infant daughter in 1783. Their oldest child, Hannah, died of it in 1792 at the age of 13, followed by ten-year-old John in 1797, 12-year-old Margaret in 1803, 19-year-old Benjamin in 1804, and 14-year-old Sarah in 1812. Both parents also succumbed to the disease, with Benjamin dying in 1806 at the age of 52, and Hannah in 1814 at the age of 59. Only three of their children lived relatively long lives, and only one, Mary, married and had children.

Mary Hodges married William Silsbee in 1808, and the couple lived here in this house, possibly with Mary’s unmarried sisters Hannah and Elizabeth. Like Mary, William was also from a prominent Salem family. His older brother Nathaniel was a ship captain and merchant who later went on to have a successful political career, serving four years in the U. S. House of Representatives and nine years in the Senate. William was likewise a merchant, with ownership interests in a number of vessels. He and Mary had seven children, and he lived in Salem until his death in 1833 at the age of 53. Four years later, Mary and her sisters sold this house, and she died in 1851 at the age of 62.

The house was subsequently owned by Stephen Webb, the cashier of the Mercantile Bank in Salem. He is not to be confused with his contemporary, Stephen Palfrey Webb, whose unusual political career involved serving as mayor of Salem from 1842 to 1845, mayor of San Francisco from 1854 to 1855, and then mayor of Salem again from 1860 to 1862. The Stephen Webb who lived here was about 34 years old when he purchased the house in 1837, and he was still living here during the 1850 census, along with his wife Martha, their five children, and two Irish-born servants. The same census valued his real estate—which may have included more than just this house—at $8,100, equivalent to about $250,000 today.

Stephen Webb had apparently died by 1870, because that year Martha—who was identified on the deed as a widow—sold the house for $3,750 to Sarah Maria Benson, the widow of Captain Samuel Benson. She died two years later, and the 1872 city directory shows her son, George Wiggin Benson, living here. At the time, his household included his ten-year-old son Frank Weston Benson, who later went on to become a prominent Impressionist painter. The future artist would live in Salem for much of his life, but was apparently only in this house for a short time, because by the 1874 city directory his father had moved to a house on Forrester Street.

During the late 19th century the house was owned by Henry Meek, who served as city clerk and later owned a publishing company. He was 54 years old in the 1900 census, and he lived here with his wife Annie, his daughter Alice, and a servant. This was apparently Henry’s second marriage, since Annie was only five years older than his 24-year-old daughter. He died later in 1900, and in 1906 Annie and Alice sold this house to Emma J. Brady.

The first photo was likely taken at some point during or shortly after the Meek family’s ownership. It was taken by Frank Cousins, a Salem native and noted photographer who used his camera to document hundreds of historic buildings in Salem and elsewhere in the northeast. The exterior of the house appears to have been well-preserved at the time, and it would have provided Cousins with a good example of colonial-era Georgian architecture.

Unlike the previous owners, Emma Brady does not appear to have lived here in this house, and instead used it as a rental property. The 1910 census shows that, at the time, it was being rented by Charles M. Proctor, a 44-year-old meat salesman who lived here with his wife Mary, their children Harrison, Charles, Arthur, Clifford, Mildred, and Gladys, and Harrison’s wife Nina. Like his father, Harrison worked as a meat salesman, while Charles was a winder at an electric works and Arthur was a farm laborer.

By the 1920 census the house had changed hands again, and at this point it was being used as a four-family home. There were a total of 11 people listed here that year, four of whom were immigrants, with three from Quebec and one from Greece. Aside from two children, all of the residents were employed, including three leather workers, two cotton mill workers, two machinists, a cook, and a rooming house keeper.

Overall, this house saw a steady decline in the prosperity of its residents, as shown by the fact that the former home of one of Salem’s most prominent captains had become a four-family apartment building. This was a common occurrence throughout Salem during this period; it had peaked in its importance as a seaport at the turn of the 19th century, when it ranked among the top ten most populous cities and towns in the country. However, Salem’s shipping industry was badly hurt by both the Embargo Act of 1807 and the War of 1812, and its merchants never fully recovered. This led to a long period of economic stagnation, and the city saw only moderate population growth during the second half of the 19th century.

From a historic preservation standpoint, though, this was not entirely a bad thing. The lack of economic or population growth led to little demand for new construction, resulting in the survival of many historic buildings. Today, one of Salem’s most visible assets is its large number of well-preserved late 18th and early 19th century homes, including the John Hodges House here on Essex Street. Although it has undergone many changes in ownership and use over the past quarter of a millennium, it stands as a reminder of the city’s historic maritime past, with few significant differences from its appearance more than a century ago when the first photo was taken. It is now one of the contributing properties in the Salem Common Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976.