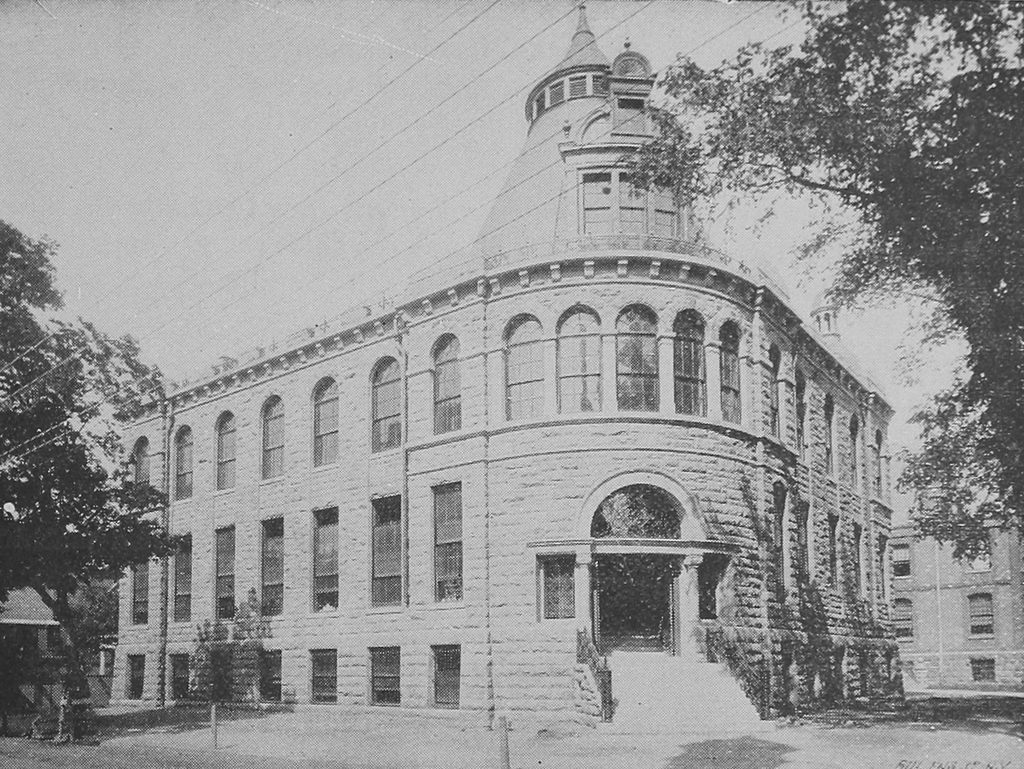

Sheffield Hall, at the corner of Prospect and Grove Streets, on the campus of Yale University in New Haven, around 1894. Image from Yale University Views (1894).

The scene in 2018:

This building had been heavily altered by the time the first photo was taken around 1894, but it was built in the early 19th century by James Hillhouse, a prominent politician who served in both the U. S. House of Representatives and the U. S. Senate. It was originally intended as a hotel, but in 1812 Hillhouse – who also served as the treasurer of Yale from 1782 to 1832 – began renting the building to Yale, as the first location of the newly-established Yale School of Medicine. The building was smaller at the time, lacking the central tower and the wings, but it included lecture rooms, study rooms, and dormitory rooms for the medical students. Two years later, Yale purchased the property for $12,500, and the School of Medicine remained here until the late 1850s, when it moved to a new facility on York Street.

The property here on Grove Street was subsequently purchased by Joseph E. Sheffield, a wealthy railroad executive who renovated and expanded the building before donating it to the Yale Scientific School. Established in 1847, this school focused on scientific education, as opposed to the more classical curriculum of Yale itself. As a result, many of the Yale students looked down on the students at the scientific school, viewing it as essentially a trade school, and for many years it was only loosely affiliated with Yale.

The renovations on this building were completed in 1860, and it housed recitation rooms, a library, and the offices of the school director. As a result of his sizable donation, the school was renamed the Sheffield Scientific School in honor of Joseph E. Sheffield, and this building became Sheffield Hall. Over the years, more buildings were added to the school, but Sheffield Hall remained here until 1931, when it was demolished in order to build Sheffield-Sterling-Strathcona Hall. The Sheffield Scientific School would eventually be fully merged with Yale University in 1956, and today this building is still standing as part of the Yale campus, as seen in the 2018 photo.