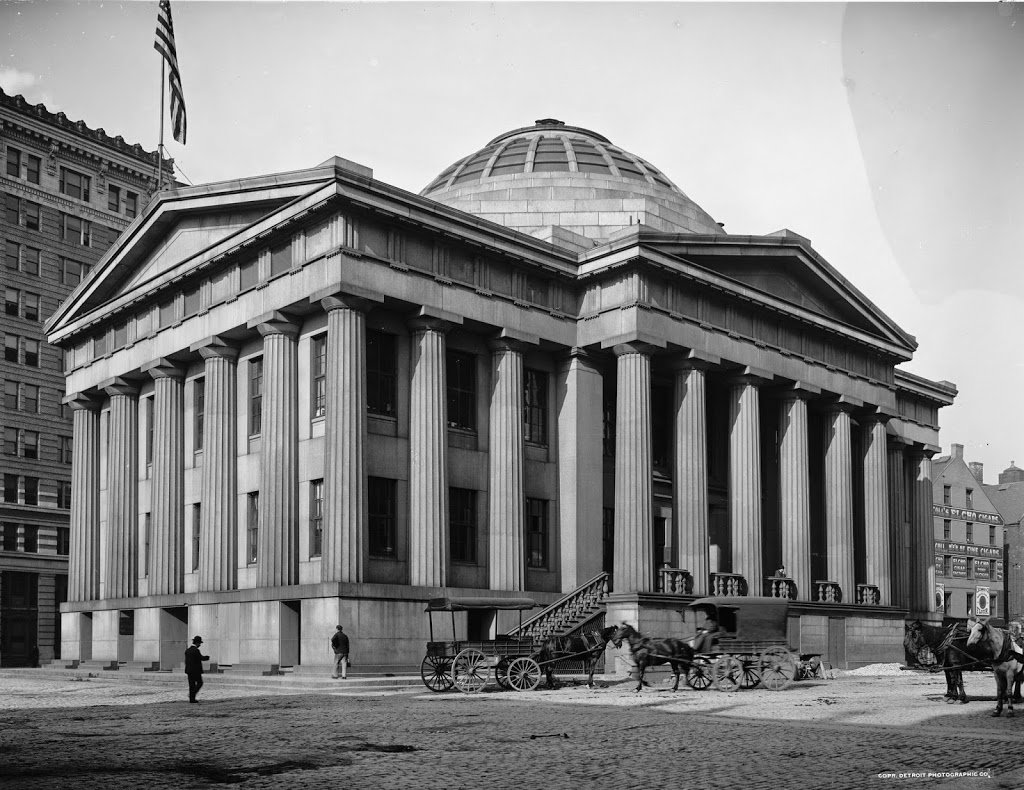

The entrances to the Park Street station, taken from in front of Park Street Church, around 1900. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2014:

The entrances to the subway are still there, as is Boston Common, but the background is very different, with the skyline of Boston’s Back Bay rising above the trees on Boston Common. Boston’s two tallest buildings can be seen here: the John Hancock Tower, which is in the center of the photo, and the Prudential Center, barely visible to the right of the John Hancock Tower. The Freedom Trail passes through this intersection, with the brick path echoing the cobblestone rows that once crossed Park Street.