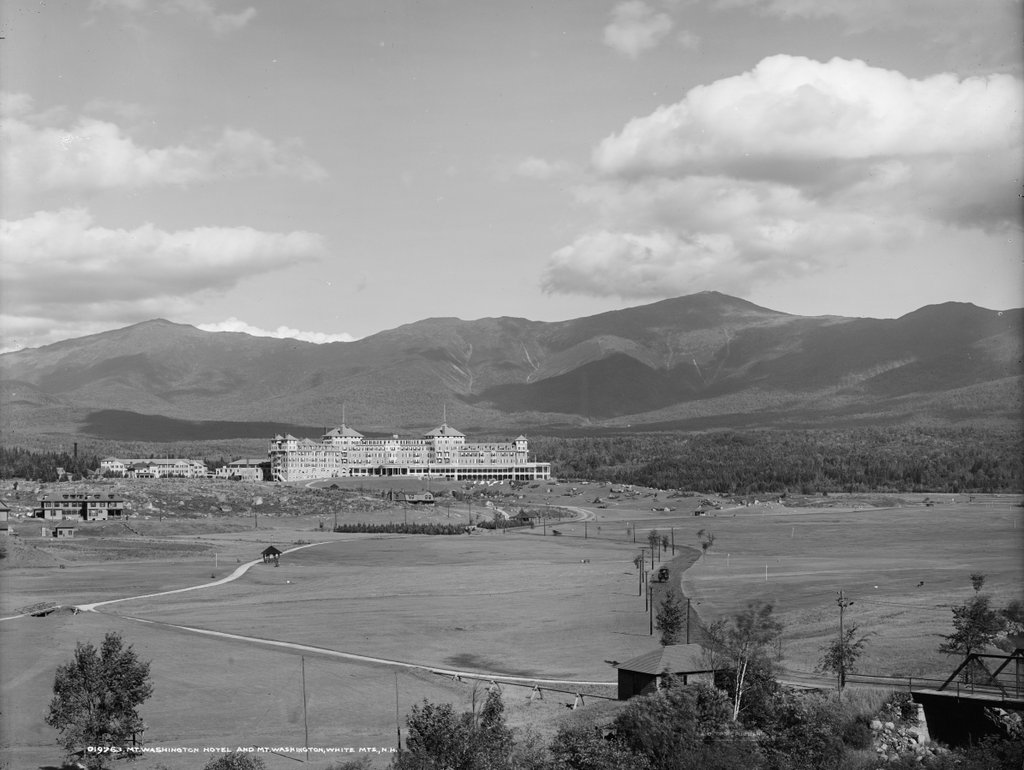

The view looking south from the northern shore of Walden Pond, around 1908. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2020:

Walden Pond is one of many glacially-formed kettle ponds scattered throughout the landscape of eastern Massachusetts. Despite its relatively small size, it is notable for being the deepest natural pond or lake in the state, with a maximum depth of 103 feet. However, it is best remembered for having been the subject of Henry David Thoreau’s 1854 book Walden. In this book, Thoreau describes the two years, two months, and two days that he spent living in a small cabin near the shore of the pond, from July 1845 to September 1847. His cabin was located about 200 feet behind where this photo was taken, just to the north of this cove, which is now known as Thoreau’s Cove.

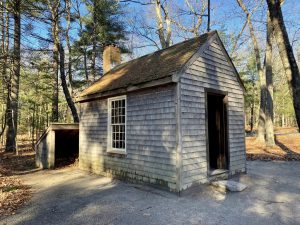

Writing in Walden, Thoreau outlined his reasons for living here at Walden Pond, explaining how, “I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” With this minimalistic approach, he constructed a one-room cabin that measured 10 feet by 15 feet, and had a chimney and fireplace at one end. It cost him a total of $28.12 to construct, mostly using recycled materials, and it was located on land owned by his mentor, fellow Transcendentalist writer Ralph Waldo Emerson. He furnished the cabin with only the basic necessities, such as a bed, a table, a desk, and three chairs.

Although Thoreau’s time here at Walden Pond is often portrayed as him living off the land in solitude, it was hardly a wilderness experience for him. The pond is just a mile and a half south of the center of Concord, and the Fitchburg Railroad ran along the western shore of the pond, a quarter mile from Thoreau’s cabin. Far from living in solitude, he frequently entertained visitors at his cabin, and he remarked in his book that he had more visitors during this period than any other time in his life. And, despite conducting an experiment in self-sufficiency, he was not above traveling into town for a home-cooked meal, or occasionally having his mother clean his dirty laundry.

Throughout the book, Thoreau frequently makes observations about the natural environment around the pond, including occasional laments about the changes that humans have made to the landscape. He contrasts the “thick and lofty pine and oak woods” of his younger years with the subsequent deforestation along the shores of the pond, and he criticizes the arrival of the railroad, describing it as a “devilish Iron Horse, whose ear-rending neigh is heard throughout the town.” However, despite such intrusions, Thoreau was confident in the unchanging nature of the pond, writing:

Nevertheless, of all the characters I have known, perhaps Walden wears best, and best preserves its purity. Many men have been likened to it, but few deserve that honor. Though the woodchoppers have laid bare first this shore and then that, and the Irish have built their sties by it, and the railroad has infringed on its border, and the ice-men have skimmed it once, it is itself unchanged, the same water which my youthful eyes fell on; all the change is in me. It has not acquired one permanent wrinkle after all its ripples. It is perennially young, and I may stand and see a swallow dip apparently to pick an insect from its surface as of yore.

Although Thoreau was the only person living along the shores of the pond at the time, he was hardly the only one to understand the value of its natural resources. He often interacted with fishermen on the pond, and in one chapter he also provided a lengthy description of the ice harvesting that occurred here on Walden Pond. At the time, naturally-produced ice was the only way to preserve perishable foods, and Boston merchant Frederic Tudor enjoyed a near monopoly on the trade, sending ships filled with New England ice to destinations as far away as India. Thoreau observed this work, likely from this vantage point here on the shore in front of his cabin, and drew parallels between the methods used for ice harvesting and farming:

In the winter of ’46–7 there came a hundred men of Hyperborean extraction swoop down on to our pond one morning, with many car-loads of ungainly-looking farming tools, sleds, ploughs, drill-barrows, turf-knives, spades, saws, rakes, and each man was armed with a double-pointed pike-staff. . .

To speak literally, a hundred Irishmen, with Yankee overseers, came from Cambridge every day to get out the ice. They divided it into cakes by methods too well known to require description, and these, being sledded to the shore, were rapidly hauled off on to an ice platform, and raised by grappling irons and block and tackle, worked by horses, on to a stack, as surely as so many barrels of flour, and there placed evenly side by side, and row upon row, as if they formed the solid base of an obelisk designed to pierce the clouds. They told me that in a good day they could get out a thousand tons, which was the yield of about one acre. . . .

Thus for sixteen days I saw from my window a hundred men at work like busy husbandmen, with teams and horses and apparently all the implements of farming, such a picture as we see on the first page of the almanac; and as often as I looked out I was reminded of the fable of the lark and the reapers, or the parable of the sower, and the like; and now they are all gone, and in thirty days more, probably, I shall look from the same window on the pure sea-green Walden water there, reflecting the clouds and the trees, and sending up its evaporations in solitude, and no traces will appear that a man has ever stood there. Perhaps I shall hear a solitary loon laugh as he dives and plumes himself, or shall see a lonely fisher in his boat, like a floating leaf, beholding his form reflected in the waves, where lately a hundred men securely labored.

Thoreau then concluded his description of the ice harvest with an observation about how interconnected the world had become, thanks to innovations such as trans-oceanic ice shipments:

Thus it appears that the sweltering inhabitants of Charleston and New Orleans, of Madras and Bombay and Calcutta, drink at my well. . . . The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges. With favoring winds it is wafted past the site of the fabulous islands of Atlantis and the Hesperides, makes the periplus of Hanno, and, floating by Ternate and Tidore and the mouth of the Persian Gulf, melts in the tropic gales of the Indian seas, and is landed in ports of which Alexander only heard the names.

Near the end of the book, Thoreau explained his reasons for leaving Walden Pond in September 1847, citing a need to move on to the next phase of his life. He then described the path that he had followed from his cabin to the shore of the pond, using it as a metaphor for the tendency of humans to fall into conformity and consistency in their behaviors and ways of thinking:

It is remarkable how easily and insensibly we fall into a particular route, and make a beaten track for ourselves. I had not lived there a week before my feet wore a path from my door to the pond-side; and though it is five or six years since I trod it, it is still quite distinct. It is true, I fear that others may have fallen into it, and so helped to keep it open. The surface of the earth is soft and impressible by the feet of men; and so with the paths which the mind travels. How worn and dusty, then, must be the highways of the world, how deep the ruts of tradition and conformity!

The exact route of Thoreau’s well-trod footpath is left to some speculation, but it seems unlikely that it would have led to this particular section of shoreline here in these photos. Despite being the closest part of the pond to his cabin, this spot offers only limited views, and the shallow, muddy water here would have made it a poor choice for bathing or collecting drinking water. In his 2018 book The Guide to Walden Pond, author Robert M. Thorson theorizes that Thoreau’s path ran along the western side of the cove, ending at the sandy beach on the far right side of the scene. From there, Thoreau could have observed the entire pond, and he would not have had to wade through the mud and weeds here at the northern end of the cove.

After Thoreau left Walden Pond, Ralph Waldo Emerson sold the cabin to his gardener, who in turn sold it to farmers who moved it to a different location in Concord. It was used for grain storage before being dismantled in 1868. As a result, the $28 cabin ultimately outlived its famous resident, as Thoreau died of tuberculosis in 1862 at the age of 44.

Over the next few decades, Thoreau’s assertion about Walden Pond preserving its purity would certainly be put to the test. The cool, clear waters of the pond drew visitors here in increasing numbers during the late 19th century, and in 1866the Fitchburg Railroad opened an amusement park and picnic ground on the western shore of the pond. Known as the Walden Lake Grove Excursion Park, it had its own stop on the railroad, and it remained here until 1902, when it burned down.

The first photo was taken several years later, around 1908. By this point, recreation on the pond had shifted to the eastern side, along present-day Route 126. During the early 20th century that section of shoreline was turned into a large, sandy beach, and in 1917 bathhouses were constructed there to accommodate visitors. Five years later, the Emerson family, along with several other landowners around the pond, donated about 80 acres to the state, and the land became the Walden Pond State Reservation.

Over the next few decades, the number of visitors to Walden Pond would continue to increase. Automobiles made it easier than ever to access the pond, and by 1935 it had nearly half a million visitors over the course of the summer, including about 25,000 on busy weekend days. The result was a struggle between conservation and recreation here at the pond, which culminated in a late 1950s proposal to “improve” much of the land around the pond with amenities such as a new parking lot. However, these plans were ultimately halted by a Superior Court judge who ruled that they violated the stipulations of the 1922 donations.

Today, more than 110 years after the first photo was taken and nearly 175 years after Thoreau moved out of his cabin, Walden Pond remains a popular destination. The parking area fills up quickly on hot summer days, and the shores of the pond are often crowded with beachgoers, swimmers, and anglers, along with the occasional literary tourist making a pilgrimage to the site of Thoreau’s cabin. For the most part, a visit to the pond today is far removed from the experience that Thoreau had here in the 1840s, and as one New York Times writer put it, “there are more selfies than there is self-reliance.”

However, the woods along the shoreline do a remarkably good job at hiding the number of visitors. The second photo was taken on a very busy July morning, yet there is surprisingly little evidence of it in the photo, save for a few swimmers far off in the distance. Overall, the landscape from the northern end of Thoreau’s Cove is not dramatically different from what he would have seen here, and if he saw it today he would likely stand by his claim that “it has not acquired one permanent wrinkle after all its ripples.”