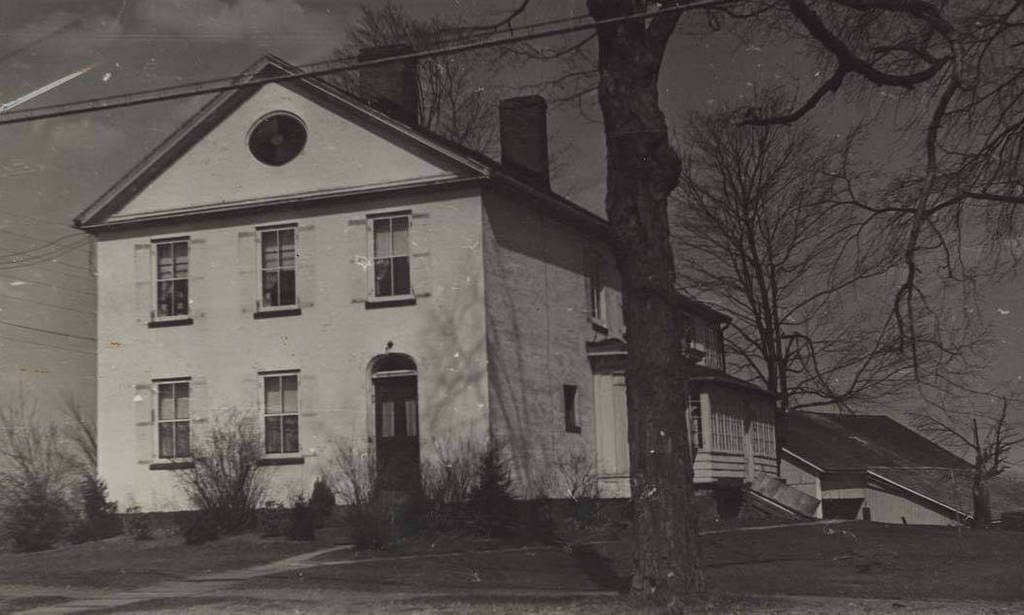

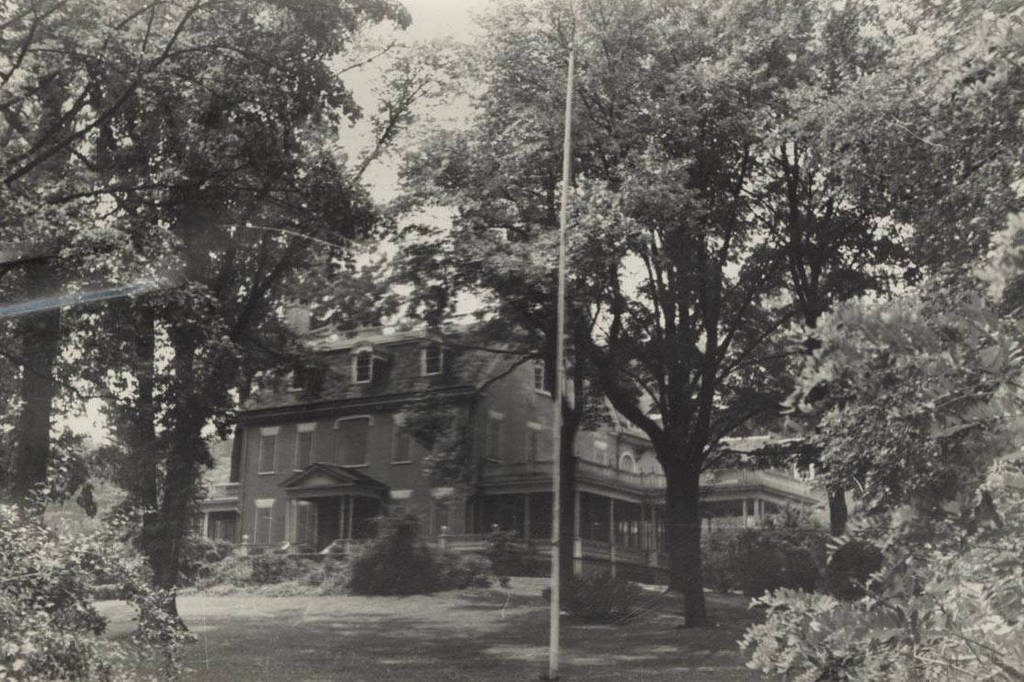

The house at 731 Hopmeadow Street in Simsbury, around 1935-1942. Image courtesy of the Connecticut State Library.

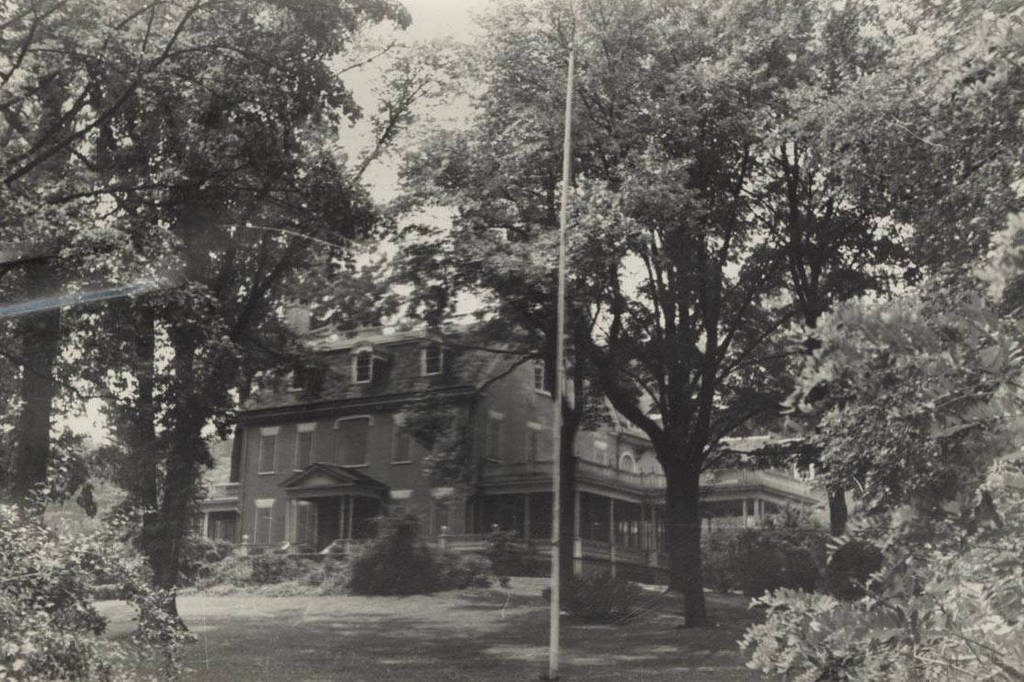

The house in 2017:

This house was built in 1822 as the home of Elisha Phelps, who belonged to one of the leading families of Simsbury. His father, Noah Phelps, was a lawyer and judge who served as an officer during the American Revolution, and later served as major general in the state militia. Likewise, Elisha became a lawyer, graduating from Yale and from Litchfield Law School before being admitted to the bar in 1803. He married his wife, Lucy Smith, in 1810, and they had five children, although their first two died in infancy.

Aside from his law practice, Elisha Phelps had an extensive political career. He served in the state House of Representatives in 1807, 1812, 1814-1818, before being elected to Congress as one of Connecticut’s at-large representatives in the U.S. House of Representatives. He served one term, from 1819 to 1821, before returning to the state legislature, where he served as Speaker of the House in 1821, and as a state senator from 1822 to 1824. He was subsequently re-elected to two terms in Congress, from 1825 to 1829, and then served for another year as the state’s Speaker of the House in 1829, before becoming the state comptroller from 1831 to 1837.

When Elisha and Lucy Phelps moved into this house in 1822, they had three surviving children. The oldest, John, was about eight years old at the time, and their daughters Lucy and Mary were about four and three, respectively. The three of them would spend the rest of their childhood here, and John would go on to attend Trinity College in Hartford, graduating in 1832. Like his father and grandfather, John became a lawyer, and in 1837 he moved to Springfield, Missouri, where he would become a prominent politician. He served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1845 to 1863, and as a colonel in the Union army during the Civil War. He was appointed by Abraham Lincoln as military governor of Arkansas in 1862, although the Senate never confirmed his appointment. However, he later went on to become governor of Missouri, serving from 1877 to 1881.

In the meantime, Elisha Phelps lived here in this house until his death in 1847, and his son-in-law, Amos Eno, inherited the property. Eno was also a Simsbury native, and had married Elisha’s daughter Lucy in 1836. However, the couple moved to New York City, where Eno established himself as a merchant and real estate developer. He invested heavily in Manhattan real estate, including building the Fifth Avenue Hotel at Madison Square in 1859. At the time, Madison Square was considered too far uptown for a fashionable hotel, but the location proved to be ideal as the city grew. He also owned land at Longacre Square, which was later renamed Times Square, and he owned a number of undeveloped lots on the Upper West Side. By the time he died in 1898, Eno’s various real estate investments were valued at over $20 million, or around $600 million in 2018 dollars.

Amos Eno’s primary residence was in New York City, but he maintained this house as his summer home, far removed from the heat, crowds, and smells of the city. During one such summer, in 1865, his grandson, Gifford Pinchot, was born here in this house. The son of James W. Pinchot and Amos’s daughter Mary, Gifford would go on to become perhaps the most notable of the many prominent descendants of Elisha Phelps. Like many of his ancestors, Gifford Pinchot attended Yale, graduating in 1889. He became a forester and conservationist, and in 1897 joined Theodore Roosevelt’s conservation-oriented Boone and Crockett Club.

In 1898, Pinchot was appointed as the nation’s Chief of the Division of Forestry, serving under presidents William McKinley and Theodore Roosevelt. In 1905, the Division of Forestry was reorganized as the United States Forest Service, and he became the agency’s first chief. He would remain in this position until 1910, when William Howard Taft, Roosevelt’s hand-picked successor in the White House, dismissed him following a dispute between Pinchot and the Secretary of the Interior. Roosevelt took this dismissal personally, as Pinchot was a close friend, and the controversy helped lead to the 1912 split in the Republican Party, between Roosevelt’s progressive wing and Taft’s more conservative wing.

Pinchot would become a major figure in the progressive movement of the 1910s, and served as president of the National Conservation Commission from 1910 to 1925. He was also touted as a possible Progressive Party candidate for president in 1916, although Pinchot declined interest and the party ultimately endorsed Republican candidate Charles Evans Hughes. However, Pinchot’s political career continued in his home state of Pennsylvania, where he served as governor from 1923 to 1927, and 1931 to 1935.

During Pinchot’s rise to national prominence, his birthplace here in Simsbury remained in his extended family. He spent many summers at the house during his childhood, and in later years would often visit his grandparents here. Amos Eno died in 1898, only a few months before Pinchot’s appointment to head the Division of Forestry, and his summer home in Simsbury was inherited by his daughter, Antoinette Wood. She made substantial alterations to the house, including having the original gabled roof replaced with a large gambrel roof, and adding a large wing to the rear of the house. She also hired prominent landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, the designer of New York’s Central Park, to create new landscaping plans for the property.

Antoinette Wood owned the house until her death in 1930, only a few years before the first photo was taken. It would remain in the Eno family until 1948, when it was sold and became a restaurant, known as The Simsbury House. Then, in 1960, it was purchased by the town of Simsbury, and underwent extensive renovations in 1985. The house is now the Simsbury 1820 House bed and breakfast, and it is on the National Register of Historic Places, as both an individual listing and as a contributing property in the Simsbury Center Historic District.