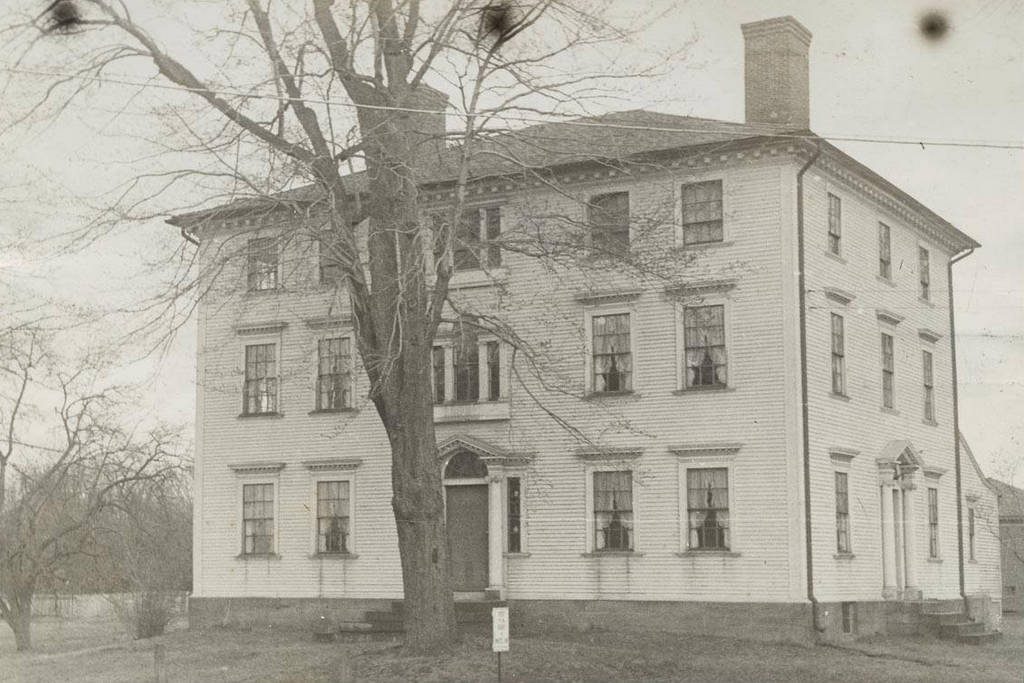

The house at 1748 Main Street in South Windsor, around 1935-1942. Image courtesy of the Connecticut State Library.

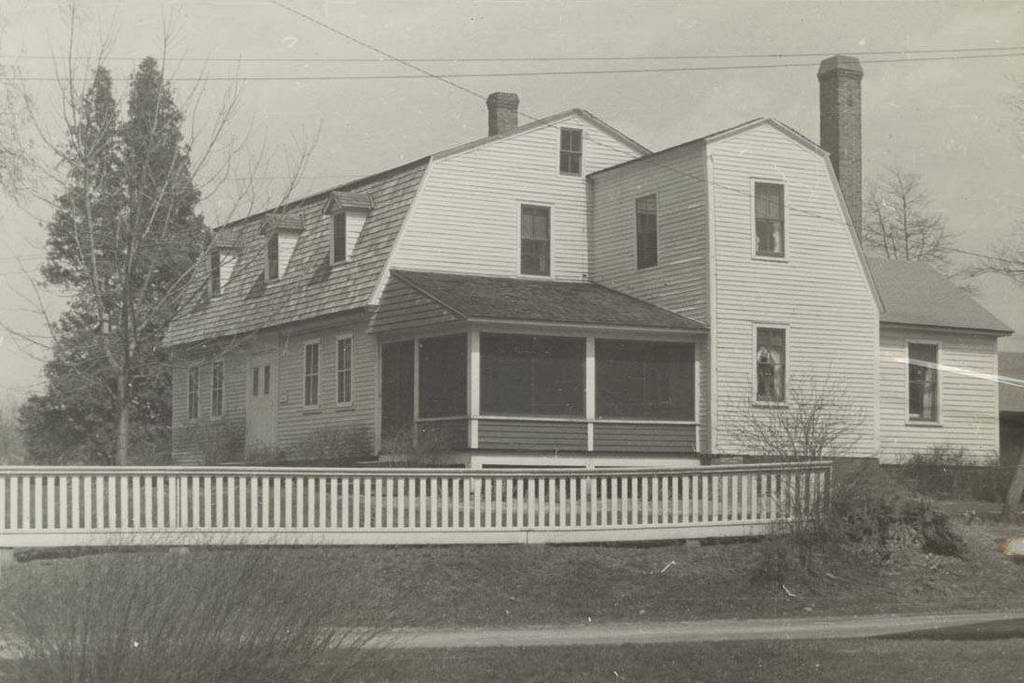

The house in 2017:

Jonathan Cogswell was born in 1782 in Rowley, Massachusetts, and was the son of Dr. Nathaniel Cogswell, a local physician. He graduated from Harvard in 1806, followed by Andover Theological Seminary, and in 1810 he was ordained as pastor of the Congregational church in Saco, Maine. A year later, he married Elizabeth Abbott, whose uncle, Samuel Abbott, was a wealthy merchant who had been one of the founders of the Andover Theological Seminary.

The Cogswells lived in Saco for 18 years, until Jonathan resigned in 1828 because of the mental and physical strain of the ministry. He and Elizabeth moved to New York City with their four daughters, but the following year he accepted a position as pastor in New Britain, Connecticut, where he remained until 1834, when he left to join the faculty of the newly-established Theological Institute of Connecticut.

The school was located in what was, at the time, part of East Windsor, and in 1834 Cogswell built this elaborate Greek Revival-style mansion directly across the street from the school. With its massive columned portico, it stands out among the mostly Colonial and Federal-style homes in the village of East Windsor Hill, and reflected his wealth and social standing. He taught church history at the school, and served as the chair of the ecclesiastical history department for the next 10 years.

In 1837, a few years after moving to East Windsor, Elizabeth died, and later in the year Jonathan remarried to Jane Kirkpatrick, the daughter of the late Andrew Kirkpatrick, who had served for many years as the chief justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court. They had two children together, and during their time in East Windsor his daughter Elizabeth was also married, to James Dixon, a lawyer from Enfield who went on to serve as a U.S. Representative and Senator.

Jonathan Cogswell remained in East Windsor until 1844, when he retired from teaching and moved to New Brunswick, New Jersey. He sold his mansion to the school, and it became the home of the president, Dr. Bennet Tyler. A year younger than Cogswell, he had graduated from Yale and served as a pastor in Connecticut before becoming president of Dartmouth College from 1822 to 1828. He subsequently returned to Connecticut, where he was one of the founders of the Theological Institute a few years later.

Tyler served as president of the school until his retirement in 1857, and he died a year later. Then, in 1865, the school moved to Hartford, where it eventually became the modern-day Hartford Seminary. The original campus here in East Windsor Hill has since been demolished, and today this house is the only surviving building from the school. Along with the rest of the neighborhood, it is now part of the East Windsor Hill Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.