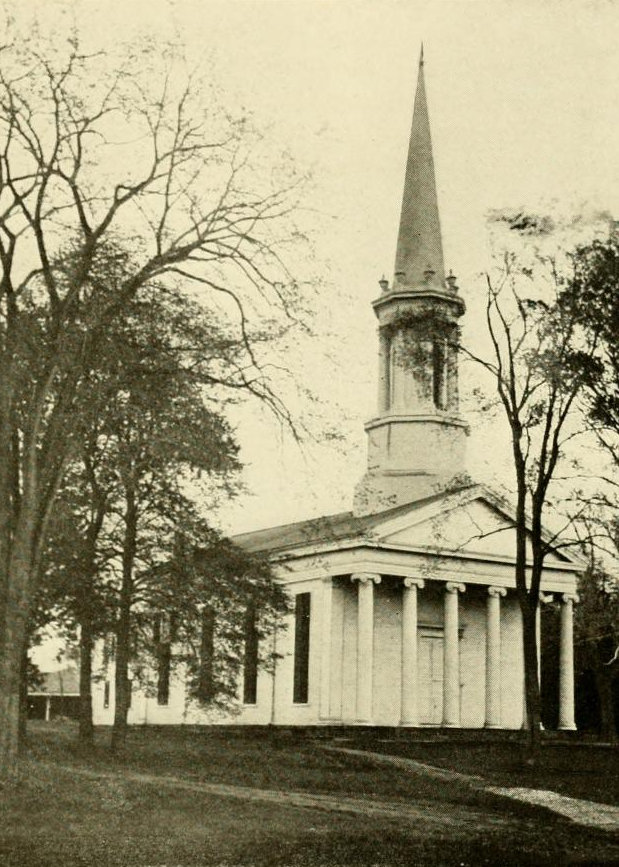

Presidents’ Row at Princeton Cemetery in Princeton, around 1903. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2019:

This section of Princeton Cemetery is located in the southwest corner of the cemetery, near the corner of Wiggins and Witherspoon Streets. It is sometimes referred to as Presidents’ Row, as it is the final resting place of many of Princeton’s early presidents. Among these, probably the most famous were Jonathan Edwards, the theologian and pastor who was one of the leaders of the Great Awakening, and John Witherspoon, who was the only clergyman to sign the Declaration of Independence. In addition, U. S. Vice President Aaron Burr—who was both the son and grandson of Princeton presidents—is buried here, and his headstone stands in the center of this scene.

The graves of the former Princeton presidents are arranged roughly in order of when they served, beginning on the far right with Aaron Burr Sr. He was the second president of the college, following the brief tenure of John Dickinson in 1747, and he served until his death in 1757. He was then succeeded by his father-in-law, Jonathan Edwards, who had previously served as pastor of the church in Northampton, Massachusetts and then a missionary to Native Americans in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Edwards was also an influential author, and he was highly sought by the school’s trustees to replace Burr. Despite reservations about his abilities, Edwards accepted the position, and was installed as president on February 16, 1758.

However, Edwards’s time as president proved to be brief. He arrived in Princeton in the midst of a smallpox outbreak, and one of his first acts as president was to receive an inoculation, in order to encourage students to do the same. Ideally, the inoculation would give Edwards only a mild case of smallpox, which would then give him lifetime immunity. Instead, though, his condition only worsened, and he died on March 22, 1758, barely a month after becoming president. He was buried here in the cemetery, just to the left of Burr’s gravestone. Edwards’s daughter Esther, the widow of Aaron Burr Sr., had cared for him during his illness, and she subsequently contracted smallpox too, dying on April 7 at the age of 26. Her death left her two children orphaned, including the two-year-old future vice president. Edwards’s wife Sarah then briefly took custody of them, but she died later in 1758 from dysentery at the age of 48.

Neither of Edwards’s next two successors as president, Samuel Davies (served 1759-1761) and Samuel Finley (1761-1766), were president for a particularly long time, and both died relatively young. They are also buried here, with Davies on the left side of Edwards and Finley on the other side of Davies. It took the school several years to replace Finley, but in 1768 Scottish minister John Witherspoon accepted the position and immigrated to the American colonies. He went on to serve as pastor for more than 25 years, and during this time he was also involved in politics. He was a New Jersey delegate to the Continental Congress throughout most of the American Revolution, and in this role he signed both the Declaration of Independence and the American Revolution. Witherspoon remained president of the college until his death in 1794, and he was buried here in the cemetery on the left side of Finley; his gravestone is the fifth from the right side of the row.

The next president after Witherspoon was Samuel Stanhope Smith, who served from 1795 until his resignation in 1812. He is buried beneath the table monument with the pillars, directly to the left of Witherspoon. Beyond Smith’s gravestone is Walter Minto, a mathematics professor who died in 1796. He is one of the few non-presidents who is buried in this plot. Then, beyond Minto’s grave on the far left side of the scene is Ashbel Green, who served as president from 1812 to 1822, and died in 1848. There are several more gravestones beyond Green, including college presidents James Carnahan and John Maclean, but these are in the distance beyond the frame of these photos.

Aside from the college presidents, the other noteworthy burial here is Aaron Burr, whose tall narrow headstone is very different from the flat tables of the presidents. As his headstone indicates, he served as a colonel in the Continental Army during the American Revolution, and he was subsequently vice president from 1801 to 1805, during Thomas Jefferson’s first term. However, he is best remembered for having killed Alexander Hamilton, and his reputation was also marred by his involvement in a bizarre plot to establish an independent country in what is now the southwestern United States. He lived in poverty for much of his later life, before marrying a wealthy widow when he was 77. However, they separated for months later, and she subsequently divorced him. Appropriately enough, her lawyer in the case was Alexander Hamilton Jr. Burr died in a Staten Island boarding house in 1836 at the age of 80, and he was interred here next to his parents and grandparents.

The first photo was taken around 1903, more than a century after many of the burials in this scene. Some of the stones appear to have fared poorly over the years, particularly those of Jonathan Edwards and Aaron Burr Sr., both of which are heavily chipped. However, the gravestones appear to have been restored since then, because they are more intact in the present-day scene than they were in 1903. Overall, this section of the cemetery has seen few changes since the first photo was taken, and the only major different in the current photo is the Princeton Public Library, which now stands in the distance on the other side of Wiggins Street.