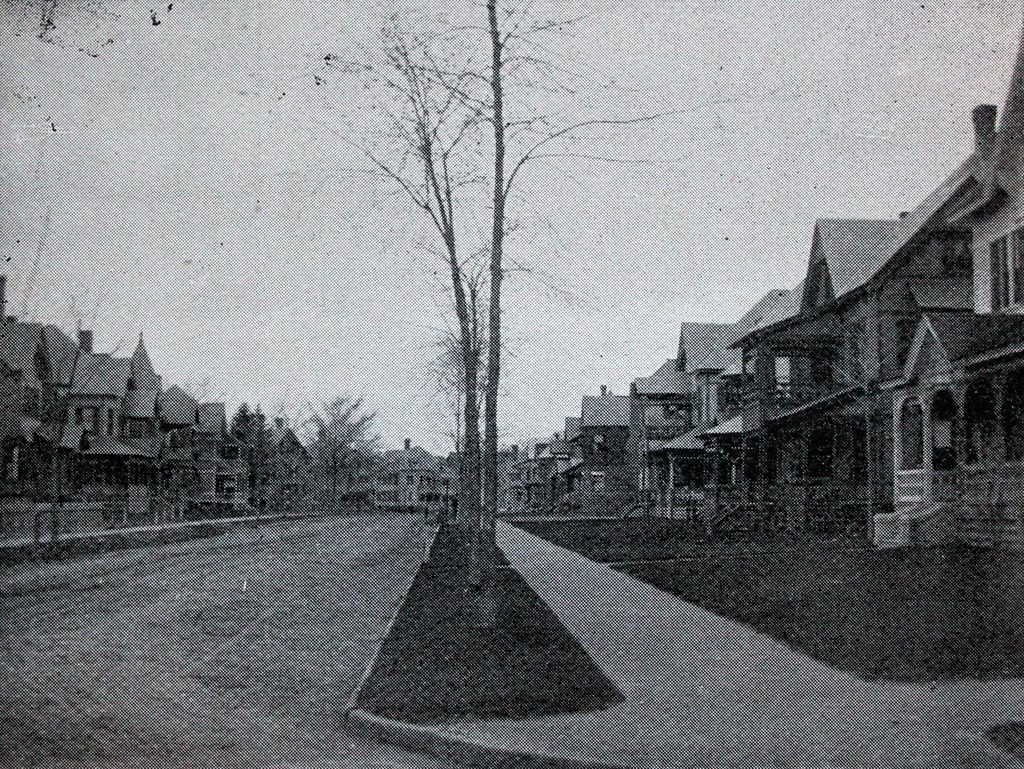

The Church of the Holy Name of Jesus, seen from the corner of South and Springfield Streets in Chicopee, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

The church in 2017:

During the mid-19th century, Chicopee began to develop into a major industrial center, with factories located along the Chicopee River at Chicopee Falls and further downstream here in the center of town. With the factories came immigrant workers, starting with the Irish and followed in later years by French-Canadians and Poles. Primarily Roman Catholic, these immigrants brought significant cultural changes to the Connecticut River Valley, which had been predominantly Congregationalist and almost exclusively Protestant until this point.

The Church of the Holy Name of Jesus was one of the first Roman Catholic churches in the area, and was built between 1857 and 1859, just to the south of the center of Chicopee. Its Gothic-style design was the work of Patrick Keely, an Irish-born architect who designed nearly 600 Catholic churches across the United States and Canada, including St. Michael’s Cathedral in nearby Springfield. Along with the church itself, the property also included the rectory, which was built around the same time and can be seen in the left center of the photo. This was followed in the late 1860s by a school for girls and a convent, and in 1881 by a school for boys, all of which were located on the opposite side of the church.

By the time the first photo was taken, around the early 1890s, both the Irish and French-Canadian immigrant groups were well-established in the area, and Polish immigrants had just started to arrive in large numbers. Primarily Catholic, many of them joined this church, and the parish records showed that Polish families accounted for nearly 30 percent of the baptisms and more than half of the marriages here at the church between 1888 and 1890. However, the Polish community soon formed a church of their own, establishing the St. Stanislaus parish in 1890 and dedicating its first building in 1895.

Around 125 years after the first photo was taken, the church is still standing, along with the rectory. although they are mostly hidden by trees in this view. The only significant change to the church over the years has been the steeple, which was struck by lightning and was replaced by the current copper spire in 1910. However, the church has been closed and boarded-up since 2011, when a renovation project uncovered deteriorating masonry and significant termite damage. The following year, the Holy Name School was closed amid declining enrollment, and in 2015 the school buildings and the convent were demolished. The church itself was not part of the demolition plan, although it remains vacant and its future seems uncertain.