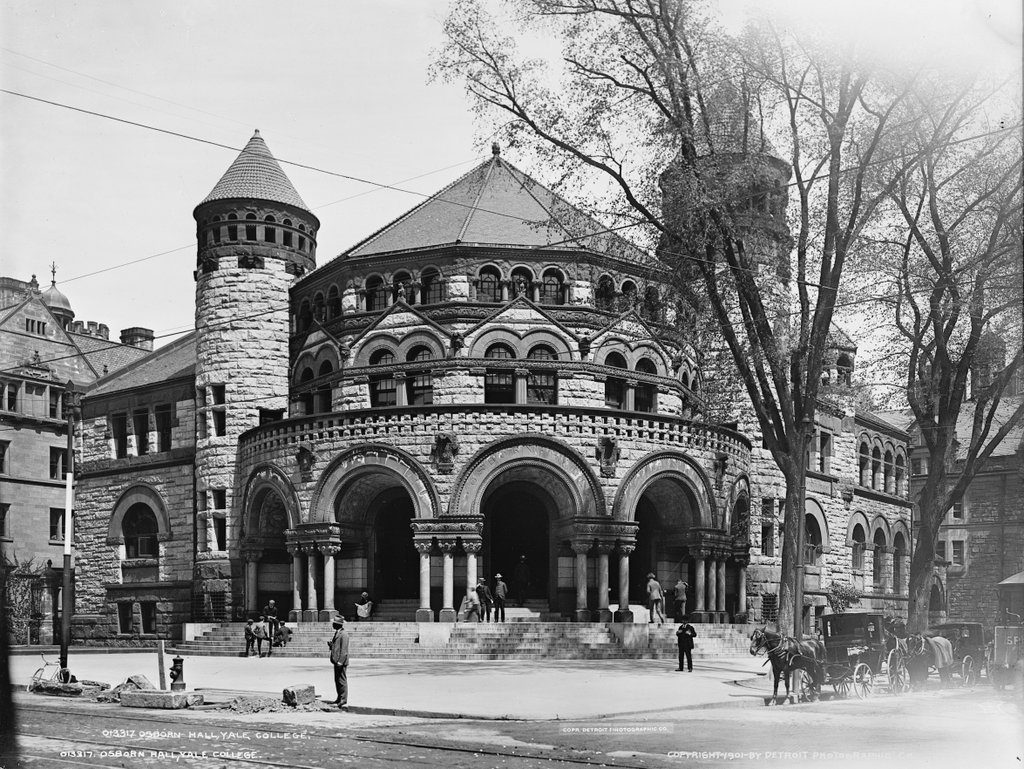

The building at the northeast corner of Bellevue Avenue and Casino Terrace in Newport, around 1903. Image courtesy of the Providence Public Library.

The building in 2018:

This block of Bellevue Avenue, from Casino Terrace north to Memorial Boulevard, consists of a row of buildings that were designed by some of the most prominent American architects of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. On the northern half of the block is the Travers Block, designed by Richard Morris Hunt, and the Newport Casino, which was one of the first major works of McKim, Mead & White. These were completed in 1872 and 1880, respectively, and they were joined several decades later by the Audrain Building, which is located at the southern end of the block. It was completed in 1903, and it was designed by Bruce Price, a New York architect who was perhaps best known for designing the Château Frontenac in Quebec City.

The Audrain Building was one of Price’s last commissions before his death in 1903, and its design reflected the popularity of Beaux-Arts architecture at the turn of the 20th century. Its most distinguishing exterior feature is the extensive use of multi-colored terra-cotta around the windows and on the cornice and balustrade. The building also has large plate glass windows, in contrast to the much smaller windows of the older commercial buildings on this block.

Upon completion, the Audrain Building had six storefronts on the ground floor, along with space for 11 offices on the second floor. At the time, Newport was one of the most desirable resort communities in the country, and the ground floor housed shops that would have catered to the city’s affluent summer residents. The first photo was evidently taken soon after it was finished, as most of the storefronts appear to still be vacant. However, at least one business seems to have moved in at this point, as the corner of the second floor features advertisements for Morten & Co., wine and cigar merchants. Other early 20th century tenants included Brooks Brothers, which opened a location here in 1909.

Newport’s status as a resort destination began to fade by the early 20th century, particularly after the Great Depression, and the Audrain Building likewise saw a decline. Perhaps most visible was the loss of the balustrade, with its distinctive terra-cotta lion statues, which was damaged in the 1938 hurricane and subsequently removed. The ground floor continued to be used for retail space, with a 1970 photo showing tenants such as a ladies’ apparel shop and a bridal shop, but these storefronts were eventually converted into medical offices.

In 1972, the Audrain Building became part of the Bellevue Avenue/Casino Historic District, which was designated as a National Historic Landmark. However, the exterior remained in its altered appearance throughout the 20th century. Finally, in 2013, the building was sold for $5.5 million, and it then underwent a $20 million renovation and restoration, including creating replicas of the original balustrade and statues. Following this project, the second floor continues to be used for office space, but the ground floor has been converted into the Audrain Automobile Museum, which has a variety of rare cars on display inside the building.