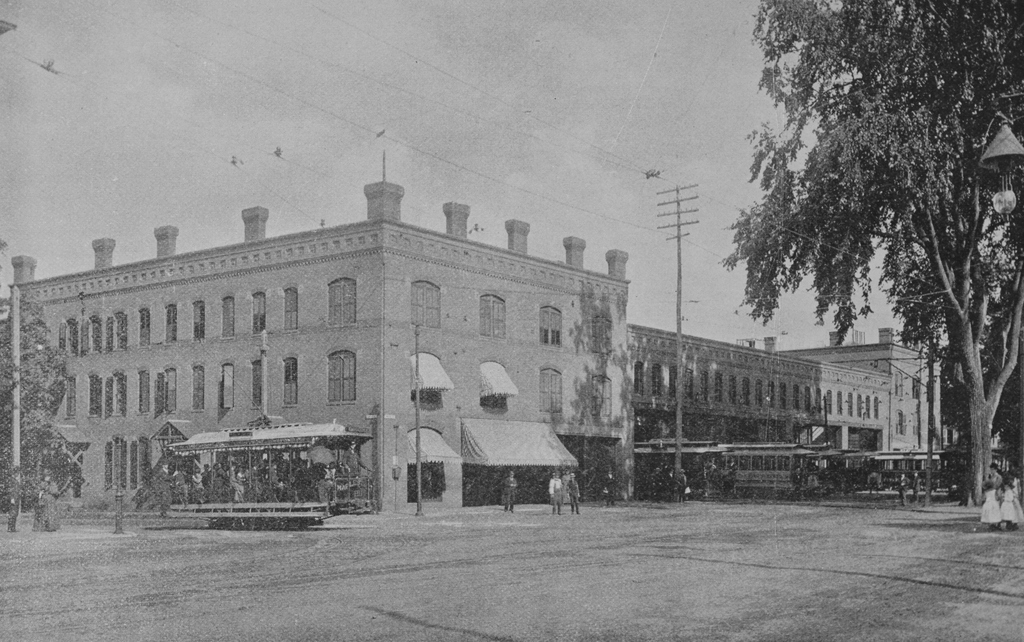

The car house of the Springfield Street Railway, seen from the corner of Main and Bond Streets in Springfield, probably in 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

The scene in 2023:

These two photos show the northeast corner of Main and Bond Streets in Springfield. When the first photo was taken, this entire block of Main Street between Bond and Carew Streets was occupied by a Springfield Street Railway car house. Also known as a trolley barn, this building was a storage and maintenance facility for trolley cars. It was one of several car houses that the railway had in the North End, which can make it difficult to trace the history of this specific building, since historical records often made references to car houses or trolley barns without precisely identifying their locations. However, this building appears to have built sometime around the late 1880s or early 1890s, around the same time that the trolley system was electrified.

The Springfield Street Railway opened in 1870, with a single line that ran on Main Street from Hooker Street to State Street, and then east on State Street as far as Oak Street, for a total length of about 2.5 miles. As was the case with other street railways of this era, its cars were pulled along the rails by horses. This had the advantage of reduced friction compared to other horse-drawn vehicles, so a single horse could pull a heavier load while also providing a more comfortable ride for passengers.

The railway proved to be popular, and it was soon expanded with lines into other city neighborhoods. By the early 1880s, the horse-drawn streetcars provided service to Winchester Park (modern-day Mason Square) via State Street, to the Armory Watershops via Maple and Central Streets, and to Mill Street via the southern part of Main Street. The railway stables were originally located at Hooker Street, but those were later supplemented with stables in a building here at the site shown in these two photos, at the southeast corner of Main and Carew Streets. However, it seems unclear whether these stables were later incorporated into the larger building in the first photo, or if the building in the photo was entirely new construction.

Although the railway was successful, it nonetheless had significant operating expenses, particularly the horses. The company eventually required a total of 280 horses for its 74 cars, and the horses outnumbered human employees (156) by almost two to one. However, an alternative emerged in the mid-1880s, with the development of electric streetcars. These cars used electric motors that drew power from overhead wires, and they were often called “trolleys” because the movement of the current collector on the wire resembled that of a fishing boat trolling lines in the water.

The first large-scale electrified streetcar system in the United States was in Richmond, which opened in 1888. The Springfield Street Railway was quick to adopt this new technology, opening its first electrified line from State Street to Sumner Avenue in Forest Park in the summer of 1890. Most other lines soon followed, and the last horse-drawn trolley—which crossed the Old Toll Bridge to West Springfield—was retired in January 1893.

The first photo was taken soon after the system was electrified, and it shows six electric trolleys in front of the car house at the southeast corner of Main and Carew Streets. Like most other early trolleys, these were generally single-truck cars, meaning that they had just one chassis, unlike the larger trolleys of the early 20th century that typically had two trucks. The trolley closest to the camera, on the far right side of the scene, helps to establish the date of the photo. The front reads “Indian Orchard,” and since the Indian Orchard line opened in 1892, the photo likely could not have been taken before then. And, since it was published in a book in 1892, the photo could not have been taken later than that year.

By this point, the company had 32.5 miles of track, with an annual ridership of over 6.3 million. For many, the trolley was a way to commute to work from the suburbs, but it was also popular for recreational excursions, especially to the more distant locations such as Forest Park and Indian Orchard. The network of trolley lines served much of the city, and also connected to the neighboring towns of West Springfield, Chicopee, and Ludlow. The company charged a flat rate fare of five cents per trip on all lines except for Ludlow, which was ten cents.

As with any change, the switch to electric trolleys did raise some issues. For some, there were general concerns about the safety of electric power and the speed of the trolleys, while other concerns focused on more specific operational issues. A September 27, 1891 article in the Springfield Republican identified some of these, including confusing schedules. A schedule for one of the lines was reprinted in the article, and it read:

State street cars leave corner Main and Carew streets for Boston road at 5.50, 6.10, 6.30, 6.50, 7.10, 7.30, 7.50, 8.10, 8.30, 8.50, 9.10 a.m. From 9:23 a.m. until 4.18 p.m. every 15 minutes. From 4.18 p.m. until 7.18 p.m., every 12 minutes. From 7.23 p.m. until 10.38 p.m., inclusive, every 15 minutes.

Such a schedule gives a good sense of the interval between cars, but it makes it more complicated to determine exact departure times, since that requires adding or subtracting increments of 12 or 15 minutes to or from the specified times. And, although not specifically mentioned in the article, the math doesn’t quite add up; the cars were supposed to leave every 15 minutes from 9:23 to 4:18, yet that timeframe is not evenly divisible by 15 minutes.

Aside from the complicated schedule, the article also explained how, in many cases, the trolleys did not consistently keep to this schedule. Several different routes, including the State Street one, originated here at the corner of Main and Carew, presumably here in this building. However, there was not always a supervisor on hand to ensure that they departed at the correct time. As explained in the article:

Some people assert that the cars are not started properly on their trips. The assistant superintendent says that he acts as car-starter, but admits that he is away from the barn a good share of the time, when, so far as his personal avowal goes, the cars take care of themselves. The transfer man, who sits on the sidewalk at the corner of Main and Carew streets and tells the conductors who have paid among the passengers, and who haven’t, says he sees the cars do not get off late, but as he never uses his watch, it is to be inferred the cars are never behind hand.

In many cases, the issue seems to have been that the cars were leaving too early, combined with the fact that the trolleys were generally able to make their trips in less time than the scheduled times. This meant that passengers who successfully deciphered the schedule and arrived at the appointed time would often discover that the trolley had left several minutes earlier. The article described how:

Now, if the conductors will only hold their cars until plump on the advertised leaving time the mechanics and wood-workers around Winchester park will be greatly pleased, for, according to these men’s testimony, the car supposed until recently to leave the upper end at 6:06 p.m. had a troublesome habit of getting off from one to three minutes early, so that the workmen are obliged to ride smutty, or hustle amazingly.

Overall, most of the issues raised in the article seemed to be relatively minor inconveniences, rather than serious safety issues. As the article observed, “[w]ith the perfection and speed and extra comfort in open cars and cushioned seats the public has grown even more exacting.” And, because it is impossible to keep everyone happy, there were simultaneously complains that the cars ran too fast and that they ran too slow; that they rang their bells too much, or not enough; and that the open cars were too cold, while the closed cars were too stuffy. The article also pointed out, rather facetiously, that “[s]ome people want the cars to run right up to their doors, and would like the conductors to carry them in, while others think it an infringement on constitutional rights if the tracks are laid through their streets.”

In the meantime, the trolley system continued to expand with new lines throughout the 1890s, reaching about 40 miles of track by 1895. All of this required a considerable amount of maintenance in order to ensure that the tracks, the overhead wires, and the trolley cars themselves were all in good condition. Much of this work occurred here in the car houses, including the one shown here in this photo. Another Springfield Republicans article, published on December 29, 1895, provided an overview of how the system was maintained, including a detailed description of the regular work that was done on the trolleys:

The company has made a practice of putting every car into the shops once every year, when it is taken all to pieces, the mechanical and electrical parts thoroughly inspected and repaired and put together as good as new. The closed cars are overhauled in the summer and the open cars in the winter and they are painted if necessary. Then there is the daily inspection. Certain men have certain cars for whose condition they are responsible. They examine their cars carefully every day and make a daily report. One man is made responsible for all the cars and he receives those reports and takes charge of the repairs. When a car is out of repair a sign “Off” is hung up on it, and if the break is serious it is sent to the shop; if not the repairs are made in the barn. The car inspectors are men who are thoroughly up in mechanical and electrical matters. When a car comes into the barn for the night there are but a few hours before it goes into use again and during these few night hours the inspectors are busy. They raise the trap doors in the floor of the car and look over the motors carefully, examining the armatures, all the wire connections, the brushes and everything else that is at all likely to get out of order. Then they go down under the car and make an equally careful observation from the outside. If you have been in the car barns you have noticed the open spaces over which the cars run. These enable the inspector to examine with grate minuteness any part of the apparatus.

The brake is the thing that is examined with the most care, for the brake has to be relied upon to save lives and property, and it is essential that it be in a state of perfection. Outside of the regular inspection of the car there is a special inspection of the brakes. One man has charge of this and he is a high-priced man. It is his duty to look at every brake each day, or rather night, for he has to make examinations while the stars shine, and once a week every car is thoroughly tested in every respect. This man has to show in writing that every car has been tested. Besides all these examinations, the machinery of the car is constantly under the observation of the motorman and conductor, who acquire a considerable knowledge of the mechanism, and there is always a man stationed at Court Square or the corner of State street to see that everything is going right. It is astonishing how quickly a difficulty can be placed. An inspector can tell from the sound of a motor not only what make it is, but whether it is in good repair. In examining the machinery they get so familiar with it that they recognize each motor as an old acquaintance. Sometimes the motors are changed about in the cars and an inspector can tell you what car a certain motor came out of.

By 1897, about five years after the first photo was taken, the railway had about 180 cars—including snowplows—that all had to be stored and maintained on a regular basis. There were three main facilities here in the North End, including the car house here on Main Street, another one nearby on the south side of Bond Street, and one on Hooker Street. According to a May 29, 1897 article in the Republican, the railway was outgrowing these car houses, which often meant that around 10 to 12 trolleys were left outdoors overnight.

At the time, the Bond Street facility had a capacity of about 75 trolleys, while Hooker Street could store about 50. Here at the Main Street car house, there was only room for about 25 cars. But, the article also noted that this was the only facility with pits below the tracks. Because part of the daily inspections involved examining beneath the trolleys, this meant that each trolley had to come through this building every night, before ultimately being moved to its overnight storage building.

This overcrowding prompted the railway to acquire more land for a new facility. In 1897, the company purchased the former Carew house, located just to the north of here on the other side of Carew Street. This house, which is partially visible in the distance behind the left-most trolley in the first photo, had been built in 1803 as the home of Joseph Carew Sr. It would remain in his family for almost a century, with his daughter Caroline Spencer living here until her death in 1895 at the age of 84. During that time, she saw her neighborhood transform from a sparsely-populated area on the outskirts of a small town, into the transit hub of a rapidly-growing city. Her death marked the end of an era here, and the house was demolished after it was purchased by the railway. In its place, the company built a new car house, which still stands today at the northeast corner of Main and Carew Streets, on the left side of the second photo.

The early 20th century would prove to be the heyday of trolleys, both in America and also here in Springfield. The book Springfield Present and Prospective, published in 1905, gave description of the street railway system, which by that point had expanded to almost 94 miles. The fleet consisted of 107 closed cars and 120 open cars, and on a typical day a total of 75 of these cars were needed in order to maintain the schedules. And, beyond just linking the suburbs to the city center, the railway had also expanded to include service between other cities in the area. The book explains how, from Springfield, trolley passengers could travel to Holyoke, Northampton, Westfield, Palmer, and Hartford without even having to make any transfers.

In 1916 the trolley system was further supported by another car house, which opened a few blocks to the north of here at the corner of Main and Hooker Streets. However, by this point automobiles were becoming affordable to middle class families, and this trend would continue into the 1920s, making public transportation less of a necessity for many people. At the same time, trolley lines around the country were steadily being replaced by buses. This was the case here in Springfield, with trolley service eventually being whittled down to just the Forest Park line. This had been the first electrified line in the system, and it would prove to be the last, with the final trolley concluding its last run— with much fanfare—in the early morning hours of June 23, 1940.

The Springfield Street Railway continued to operate under this name for many years, despite being a “railway” in name only, with buses having replaced all of the former trolley lines. It eventually merged to form the Pioneer Valley Transit Authority, which continues to provide bus service to Springfield and the other communities in the region.

Two of the former trolley barns still exist today. The one at Hooker Street is now used as a bus garage, and the one at the northeast corner of Main and Carew has been converted to other commercial uses. It is visible in the distance on the left side of the second photo, and it remains a distinctive landmark in the North End.

As for the trolley barn in the top photo, it was later converted into commercial and retail use. It stood here until it was destroyed by a fire in December 1971. The site of the building is now a gas station, and the contrast between these two photos provides a vivid illustration of the old trolleys and the newer method of transportation that replaced them.