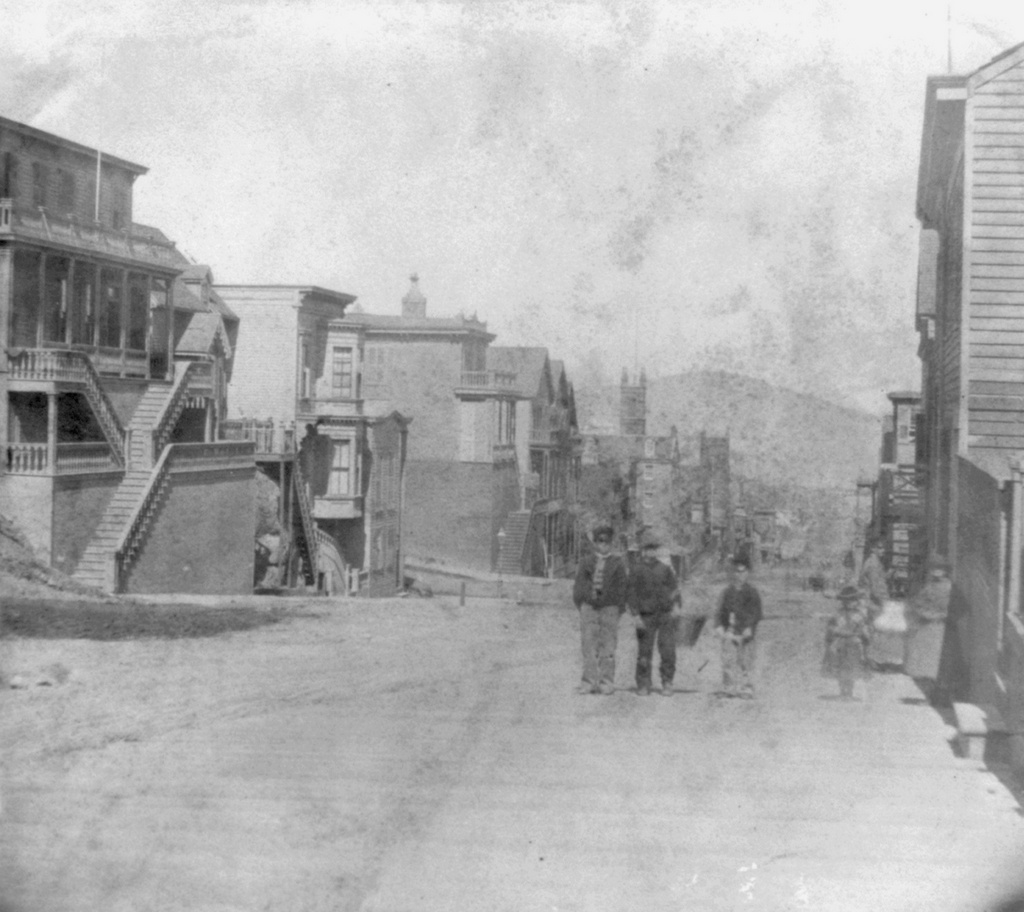

Looking down Sacramento Street from the corner of Powell Street in San Francisco, around 1866. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Lawrence & Houseworth Collection.

Sacramento Street in 2015:

The first photo here was taken just a half block further up the hill from where, 40 years later, Arnold Genthe would take his famous photograph of the earthquake. Much of this view had changed by 1906, but many of the buildings from this 1866 view were still standing up until the fires destroyed this entire scene. One of the few buildings that survives today from the 1866 photo – in fact, it may be the only one left – is the church on the right side. This is the Old Saint Mary’s Cathedral, which was built in 1854 and, although gutted by the fires in 1906, was repaired and is still standing at the corner of California and Grant Streets.

The view of the church from here is now blocked by modern buildings, and the city’s skyline has obviously changed considerably in the 150 years since the first photo was taken. In the distance down Sacramento Street is the Financial District with its skyscrapers, and at the very end of the street, barely visible, is the Ferry Building, which was built over 30 years after the first photo was taken,. It was one of the few historic buildings still standing in this scene, and also one of the few that survived both the earthquake and the fires.

This post is part of a series of photos that I took in California this past winter. Click here to see the other posts in the “Lost New England Goes West” series.