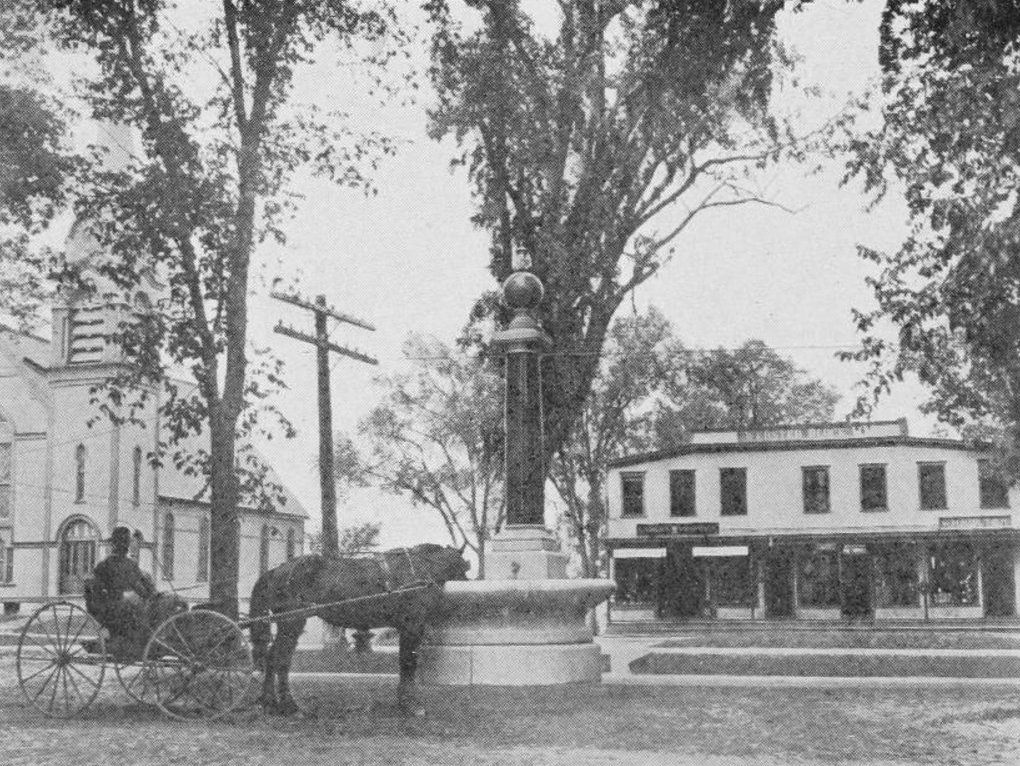

The Powers Institute on Church Street in Bernardston, around 1891. Image from Picturesque Franklin (1891).

The scene in 2017:

Massachusetts has long had a strong reputation for its educational system, with public schools dating back to the early days of the colonial era, but it was not until the second half of the 19th century that public high schools became common across the state. Prior to then, public high schools were typically only found in larger cities and towns, but many smaller towns were served by private schools, which were often founded by local benefactors. Here in Bernardston, the Powers Institute was established in 1857, two years after the death of Bernardston native Edward Eppes Powers. In his will, Powers gave the town 100 shares of the Franklin County Bank, which were valued at $10,000. Half of the income from this investment was to be used to support the town’s public elementary schools, while the other half was to be used to open a high school.

This Italianate-style school building was built in 1857 for the Powers Institute, on land that had been donated to the town by other benefactors. It served as a quasi-public high school throughout the 19th century, providing free education for Bernardston residents while charging tuition for out-of-town students. In 1860, Cushman Hall was built on the other side of Church Street, and was given to the town as a boarding house for tuition students. By the 1870s, the cost of tuition was $8 per term (around $180 today), and board was $4 per week, although students also had the option to self-board in furnished rooms that were provided for 35 cents per week.

During its peak in the 1860s, the school had several hundred students per year. However, the enrollment steadily dropped over the next few decades, eventually reaching just 61 students in 1891. By around the turn of the century, it had become more of a standard public school, and the state began subsidizing the tuition of out-of-town students, provided that they lived in a town that was too small to support its own high school. In this new role, the Powers Institute would continue to serve as the town’s public middle and high school for many years, but it finally closed in 1958, when Bernardston students began attending the Pioneer Valley Regional School in nearby Northfield.

After the Powers Institute closed, the old school building became the home of the Bernardston Historical Society, which runs a museum here. It is hard to tell from the first photo because of all the trees in the foreground, but the exterior of the building has not seen any significant changes over the years, and it stands as a rare example of a mid-19th century Italianate school building in the Connecticut River Valley. Because of this, the school building, along with Cushman Hall and the neighboring Cushman Library, is now part of the Powers Institute Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1994.