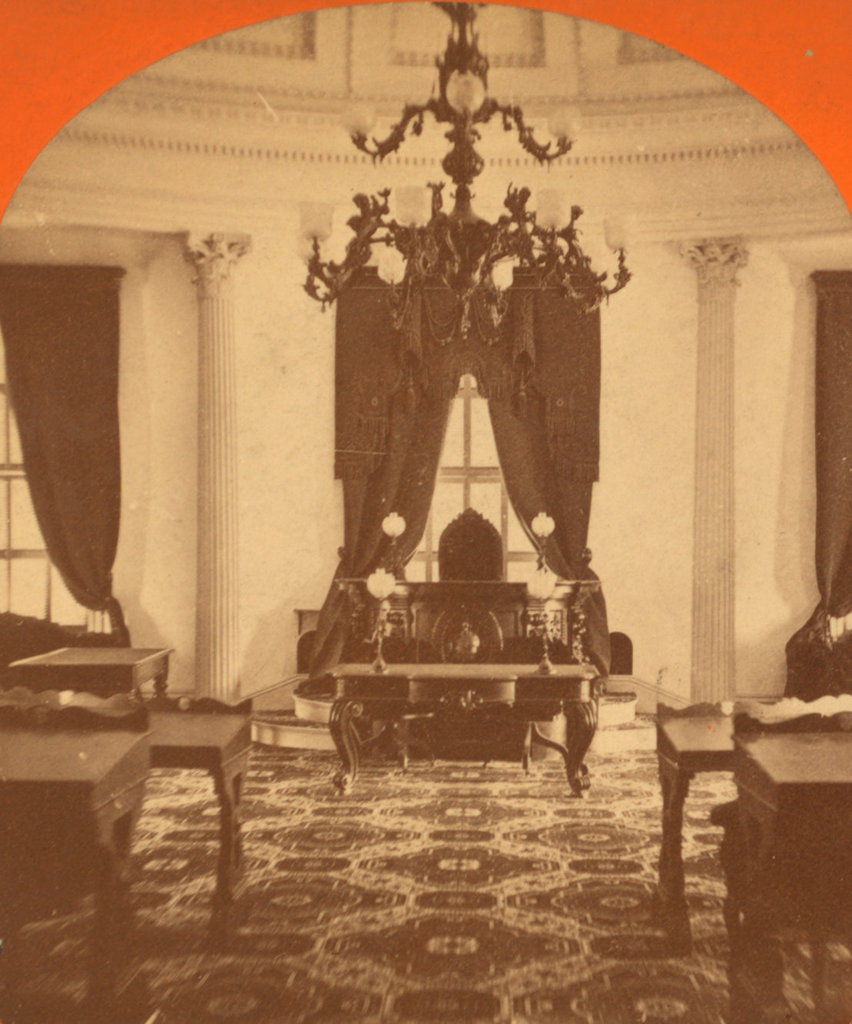

The Senate chamber in the Vermont State House, around 1865-1875. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The scene in 2019:

Vermont originally had a unicameral legislature, but in 1836 the state added a senate, which consisted of 30 members elected from Vermont’s 14 counties. Each county was guaranteed one senate seat, and the remaining seats were allocated to the counties based on population. By contrast, the Vermont House of Representatives was comprised of one representative from each town, regardless of population, which gave a disproportionately large voice to the state’s many sparsely-populated towns. In this sense, representation in the Vermont state legislature was essentially the opposite of the U. S. Congress, where each state has two senators but a varying number of representatives.

The present state senate chamber, shown here in these two photos, has been in use since 1859, when the current state house was completed. It is located in the eastern wing of the building, and these two photos show the view looking down the central aisle from the rear of the chamber. Shortly after the state house opened, the Vermont Watchman & State Journal published an article about the building, which included a lengthy description of the senate chamber:

The Senate Chamber . . . is elliptical in form, 46 by 38 feet, 22 feet high, adorned with Corinthian fluted columns, having carved capitals, supporting an entablature, from which springs a cove ceiling, continuing the outline of the ellipse.

This ceiling is moulded and enriched in panels, having counter curved heads ornamented in stucco, and bead and button mouldings in the beams, terminating in a moulded rim of elliptical form, surrounding yet other ornamental panels, with circular returns and ornaments in between, on the flat of the ceiling, converging to the centre piece, from which is hung a massive twelve light chandelier. The lobbies are adorned with fluted columns, having bases and Corinthian capitals, resting on a pedestal, and supporting an entablature and open balustrade of the gallery. In front of the balustrade and fitted between the rails and base is a neat marble-faced clock.

The lobbies are parallel to the curve of the room, returned by a quarter circle to the wall. The President’s desk is of solid black walnut, of highly ornamental pattern, designed by the Architect especially for the place, and made, as was also the Secretary’s table, and the furniture and upholstery of the entire building, by Blake & Davenport, of Boston, under the immediate direction of John A. Ellis. The desk is curved and irregular in outline, paneled and cvarved, and has at each projection in front a carved buttress, and in the centre panel the coat of arms of the State of Vermont is elegantly carved.

The Senators’ desks and chairs are designed and arranged so as to give ample space for the comfort and convenience of Senators. The furniture throughout the building is of black walnut. The carpeting, which was furnished by Lovejoy & Wood, of Boston, is excellent in quality and well adapted to the various rooms.

The first photo was taken within a decade or after this description was published. Like the nearby House of Representatives chamber, the Senate chamber has remained largely unchanged since then. In this scene, the only significant difference is the addition of two computer desks in front of the rostrum.

The Senate itself has also retained the same basic structure over the years, unlike the House, which was dramatically altered by reapportionment in 1965. The only major difference is that the Senate districts no longer strictly follow county lines; some districts include towns from neighboring counties, in order to ensure equal representation. In addition, two of the smaller counties, Essex and Orleans, have been combined into a single district, making 13 total districts. However, as was the case in the 19th century, these districts continue to have multiple members based on population. They range from the three smallest, which only have one senator each, to the largest, Chittenden, which has six senators in its district.