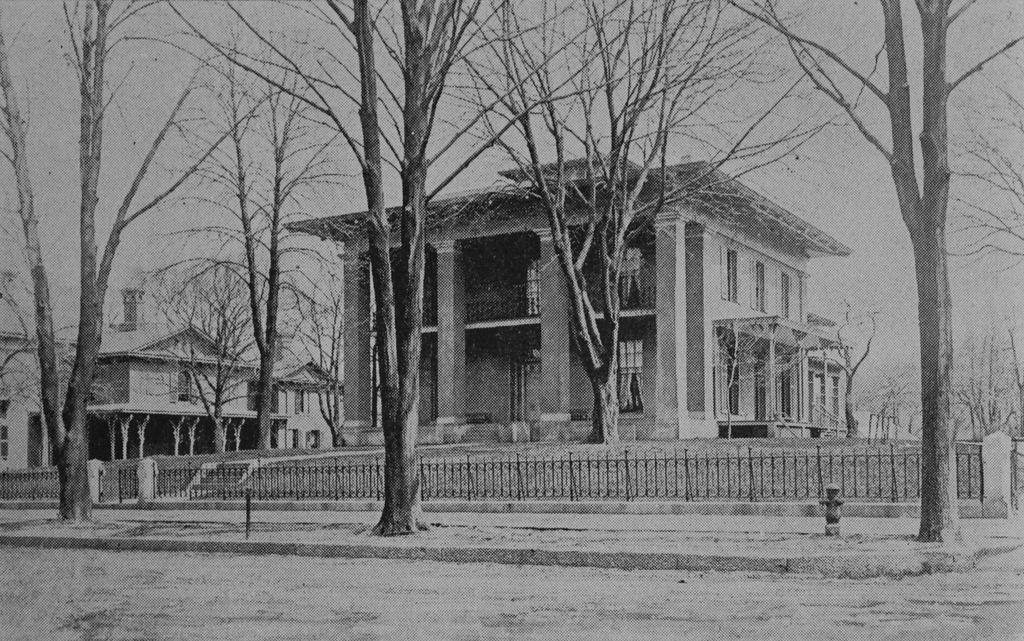

The house at the southeast corner of Chestnut and Mattoon Streets in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The scene in 2016:

In the mid-1800s, this section of Chestnut Street was owned by artist Chester Harding, who had a spacious lot and a large home that was set back from the street. After his death in 1866, though, it was sold to William Mattoon, who subdivided the property and built Mattoon Street through it. Over the next two decades, the street was developed with brick Victorian townhouses on either side, most of which are still standing today as one of the city’s great architectural treasures.

Here at the corner of Chestnut and Mattoon, the house in the first photo was built around the mid-1870s, during the same time that Mattoon Street was being developed. Although it faced Chestnut Street, it matched the adjoining townhouses around the corner with its Second Empire-style architecture.

One of its early residents was Levi B. Taylor, who was living here by 1882 and remained here for the rest of his life. A native of Granby, Massachusetts, Taylor was an inventor and salesman, and for many years he worked as a traveling salesman for the American Knife & Shear Company. He died in 1897 at the age of 58 while in Peoria, Illinois, and the house went through several other owners over the next few decades.

By the time the first photo was taken, Chestnut Street had undergone some dramatic changes. The predominantly residential street had become far more commercial, and most of the 19th century mansions were gone by the 1930s. This house was still standing, although at this point it had been altered to include a storefront, which housed the Bay Path Spa. It was named for Bay Path Institute, which was at the time located directly across Chestnut Street from here, and the store catered to its students until the school moved to its current location in Longmeadow in 1945. The old house was demolished at some point afterward, and in 1959 the current liquor store was built on the site.