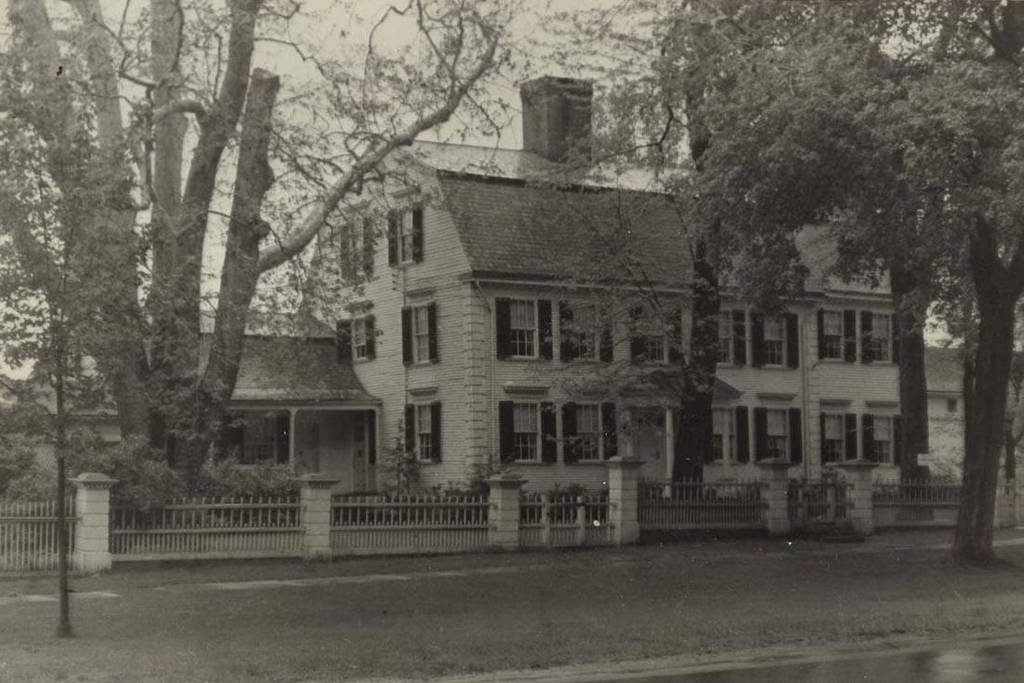

The Phelps-Hatheway House on South Main Street in Suffield, around 1935-1942. Image courtesy of the Connecticut State Library.

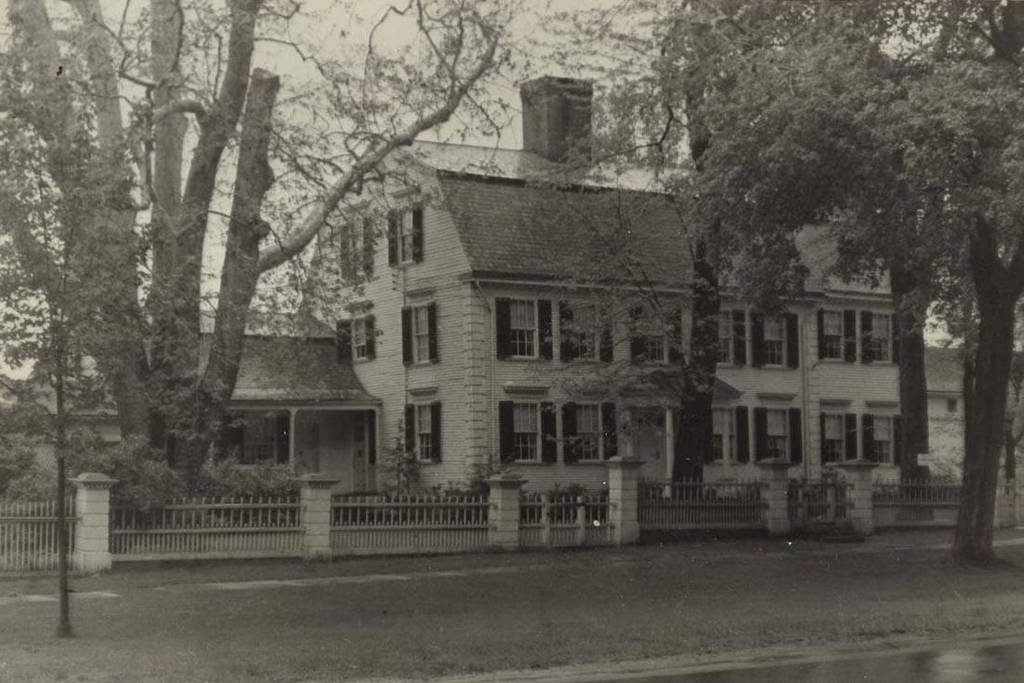

The house in 2017:

This elegant Georgian-style home is a prominent architectural landmark in the Connecticut River Valley, and is one of the finest 18th century homes in the entire region. As mentioned in an earlier post, it was built sometime between the 1730s and 1761 for Abraham Burbank, and the house was later inherited by his son Shem. At the time, the house was much smaller, consisting of just the central portion. It had a gabled roof, and lacked the ornamentation that was later added. Shem was a merchant, as well as a captain in the state militia prior to the American Revolution. However, like many other wealthy merchants in the area, he was also a Tory, and sided with the British during the war. As a result, his business suffered, and in 1788 he had to sell the house.

The next owner of the house was Oliver Phelps, who, like Burbank, had been a merchant. However, unlike Burbank, he had been on the winning side of the American Revolution, serving as a deputy commissary for the Continental Army. He was originally from Granville, Massachusetts, and served in both houses of the Massachusetts legislature. He was also a delegate to the state’s constitutional convention in 1779-1780, and served on the Governor’s Council in 1786. At this point he was a wealthy man, and in 1788 he formed a partnership with Nathaniel Gorham, who had been one of the delegates to the US Constitutional Convention the year before. Together, they purchased six million acres of land in western New York for one million dollars, and that same year Phelps purchased this house from Shem Burbank.

Around 1794 set about expanding the house with a new wing on the right side, as well as adding ornamentation to the exterior. This brought the house up to architectural tastes of the late 18th century, and it also reflected his considerable wealth and social standing. Some of the remodeling was done by a young local architect, Asher Benjamin. About 21 years old at the time, he would go on to become one of the nation’s leading architects, and this house is his earliest known work. Phelps also had the interior decorated lavishly, including with imported French wallpaper that still covers the walls of the house today.

During this time, Phelps also continued his land speculation, purchasing vast tracts of land in present-day Ohio, Georgia, West Virginia, and northern Maine. By 1800, he was, according to some sources, the largest private landowner in the country, but this ultimately led to his downfall when land values dropped. Deeply in debt, he sold his house in 1802 and moved to Canandaigua, New York, which had been part of his initial land purchase in 1788. He served a term in Congress from 1803 to 1805, but his financial troubles continued, and he died in debtor’s prison in 1809.

Apparently undeterred by the financial ruin of its two previous owners, Asahel Hatheway purchased the house from Phelps in 1802. He had grown up at his parents’ house just a little south of here, and studied theology at Yale. After graduation, he briefly worked as a pastor, but then returned to Suffield, where he became a farmer and a merchant, along with serving as a church deacon and a justice of the peace. He married his wife Anna in 1778, and they had six children together. Anna died in 1807, only about five years after moving into this house, but Asahel continued living here until his death in 1828, at the age of 89.

The house was inherited by his son, Asahel, Jr. Like his father, the younger Asahel had graduated from Yale, and became a merchant in New York City before returning to Suffield in 1812. He and his wife Nancy had six children, and he died in 1829 at the age of 49, just a year after his father’s death. His daughter Louise, who was only a few years old when he died, became the third generation of Hatheways to own the house. She never married, and lived here for the rest of her life, until her death in 1910. The 250th anniversary book of Suffield, published a decade later, describes how “her stately dignity and gracious but firm refusal to open her home to any but a few intimates imparted to the old mansion an air of mystery.”

Louise was the last living descendant of Asahel Hatheway, Sr., and after her death many of the family heirlooms were donated to the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford. The house is now owned by Connecticut Landmarks, a preservation organization that maintains several historic houses in the state. Both the exterior and interior have been remarkably well-preserved, and the house is open to the public for tours. Even older than the house itself, though, is the massive sycamore tree on the left side of both photos. It is approximately 300 years old, predating the house by several decades, and aside from the loss of a large limb it has not changed much in the 80 years since the first photo was taken.