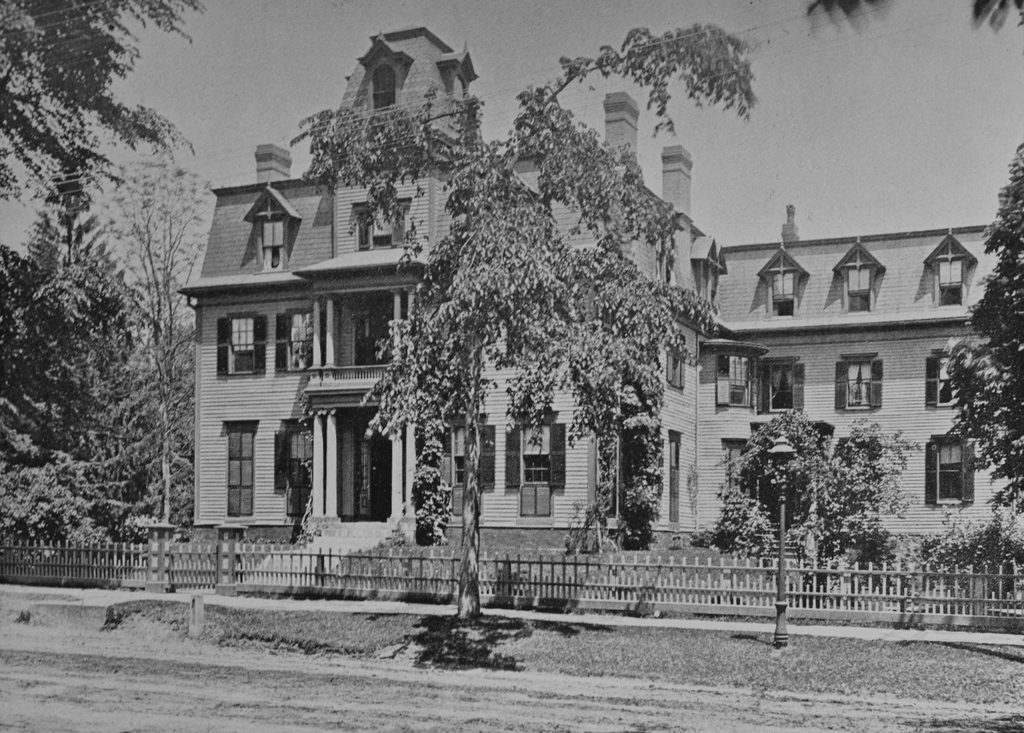

The Burnham School on Elm Street in Northampton, around 1894. Image from Northampton: The Meadow City (1894).

The scene in 2017:

This house was built sometime around 1810, although it has been significantly altered over the years. It was originally the home of Elijah Hunt Mills, a lawyer and politician who served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1815 to 1819, and in the U.S. Senate from 1820 to 1827. Mills was also one of the founders of the Northampton Law School, a short-lived but notable law school whose students included future president Franklin Pierce. Because of ill health, Mills retired from the Senate at the end of his term in 1827, and about a year later he left the Northampton Law School, which closed soon after. He lived here in this house until his death in 1829, and the house was subsequently owned by Thomas Napier, a Southerner who was was apparently a slave auctioneer and a vocal anti-abolitionist.

By the mid-19th century, this house was owned by Samuel L. Hinckley, whose occupation was described as “gentleman” in the 1860 census. Born Samuel Hinckley Lyman in 1810, he legally changed his name in 1831 at the request of his grandfather, Judge Samuel Hinckley, in order to carry on the Hinckley family name. After graduating from Williams College, Hinckley married Henrietta E. Rose, although they were married for less than a year before her death, soon after the birth of their only child, Henry. Hinckley later remarried to Ann L. Parker, and they had four children together. By the 1860 census, all seven family members were living here in this house, along with three servants. At the time, Hinckley’s real estate was valued at $15,000, plus a personal estate of $40,000, for a total net worth equal to about $1.5 million today.

The house was subsequently owned by Hinckley’s younger brother, Jonathan Huntington Lyman, a physician who was living here by the 1865 state census. He received his M.D. from the University of Pennsylvania in 1840, and in 1847 he married his first wife, Julia Dwight. She came from a prominent family, and both of her grandfathers were among the most influential men in late 18th and early 19th century New England. Her father’s father was Timothy Dwight IV, the noted pastor, theologian, and author who served as president of Yale from 1795 to 1817, and her mother’s father was Caleb Strong, a Northampton lawyer who served as a delegate to the U.S. Constitutional Convention in 1787, a U.S. senator from 1789 to 1796, and governor of Massachusetts from 1800 to 1807 and 1812 to 1816.

Jonathan and Julia Lyman had three children together, but Julia died of tuberculosis in 1853 at the age of 29. Two years later, he remarried to her older sister Mary, and by 1865 they were living here with Jonathan’s two surviving children, John and Francis, plus two servants. Francis died in 1871 from yellow fever at the age of 18, while in Brazil studying natural history, and John went on to become a physician, after graduating from Harvard Medical School in 1872.

In 1877, Jonathan sold the property to Mary A. Burnham, who established a school for girls here in this house. Originally called the Classical School for Girls, it opened in 1877 with the goal of preparing girls for the newly-established Smith College, located directly across the street from here. Only 22 students were enrolled during this first school year, but the school soon grew, and by the time the first photo was taken there were 175 students on a campus that included several other buildings. Mary Burnham died in 1885, and assistant principal Bessie T. Capen subsequently took over the school, which was renamed the Mary A. Burnham School in honor of its founder.

By the time the first photo was taken, very little remained of the house’s early 19th century appearance. It originally had Federal-style architecture, as seen with features such as the second-story Palladian window, but after its conversion to a school a wing was added to the right side, and the original part of the house was altered with a Mansard roof, dormer windows, and a tower above the main entrance.

The house would remain part of the Burnham School for many years, but in 1968 the school merged with the Stoneleigh-Prospect Hill School in Greenfield, forming the present-day Stoneleigh-Burnham School. The Northampton campus was then sold to Smith College, which converted this building into student housing. It is now known as the Chase House, in honor of writer and Smith professor Mary Ellen Chase, and it is attached to the neighboring Duckett House, just out of view to the right. Over the years, the house has lost some of its Victorian-era elements, particularly the tower, but it still stands today as one of many historic homes along Elm Street.