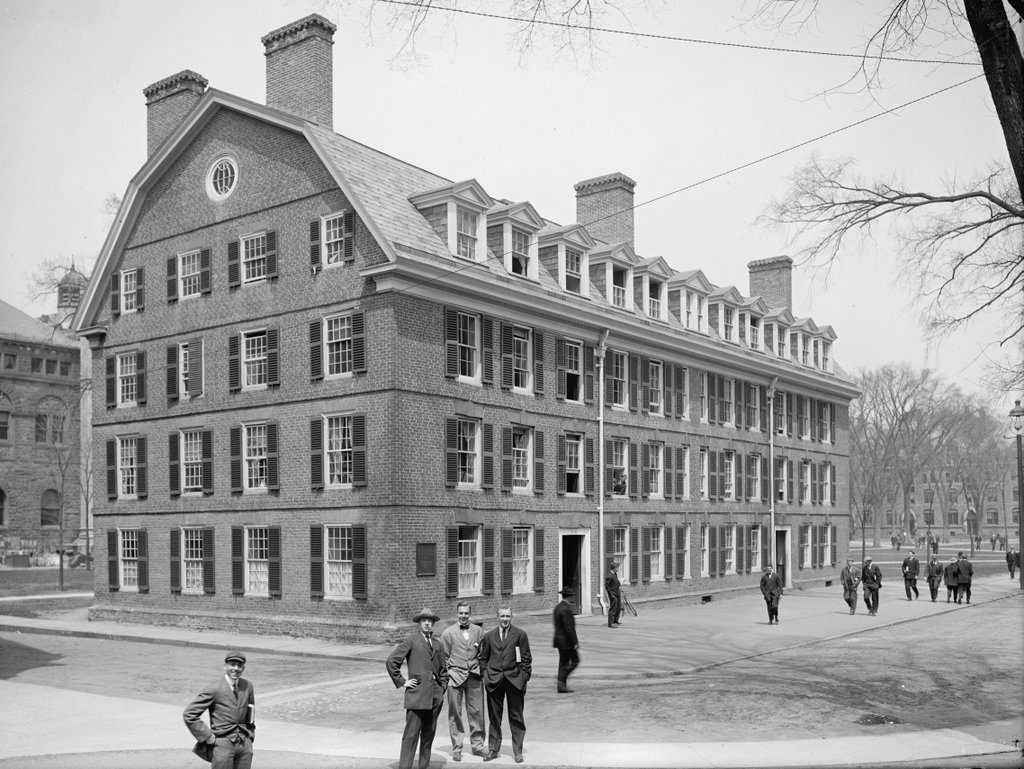

Another view of the Mount Vernon mansion, seen from the bowling green on the west side of the house, around the 1860s or 1870s. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

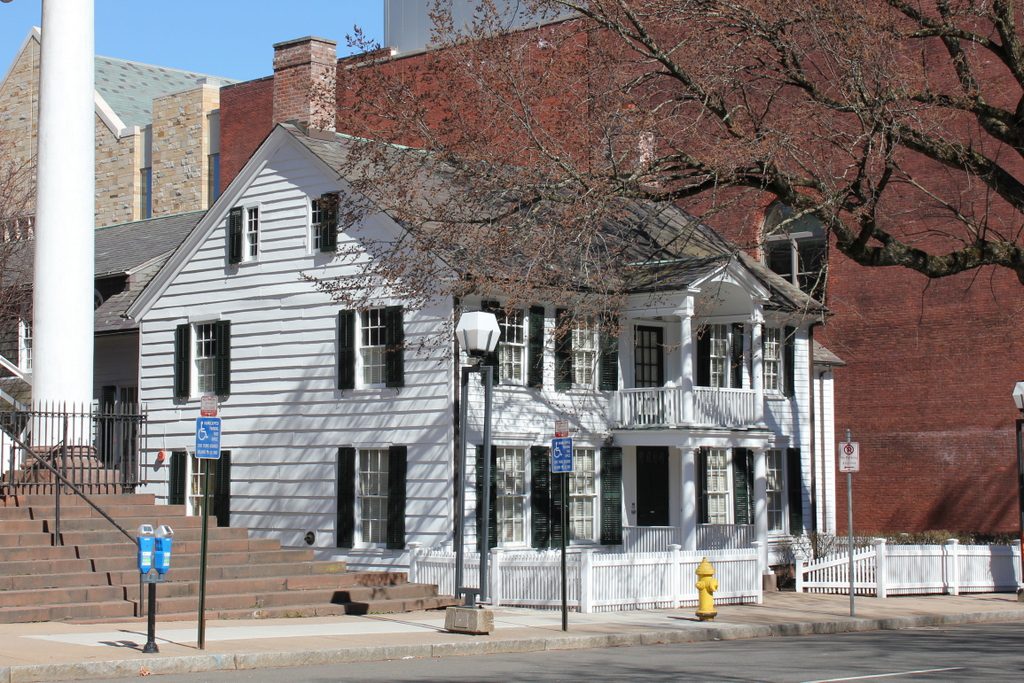

The mansion in 2018:

As discussed in the previous post, the Mount Vernon estate had been in the Washington family since 1674, when John Washington acquired the land. However, it was his grandson, Augustine Washington – the father of the future president – who constructed the original section of the mansion here on this site, in 1734. At the time, it was only one story, with a garret for the second floor, and it was comprised of what is now the four windows in the middle of the house.

George Washington’s older half brother, Lawrence Washington, later received the property from their father, and he lived here until his death in 1752. His widow, Anne, subsequently leased Mount Vernon to George Washington, starting in 1754. Four years later, he began the first expansion of the house, adding a full second floor with a garret above it. He gained ownership of the estate when Anne died in 1761, and in 1774 he embarked on an even more ambitious project, with two-story additions on both sides of the house.

The mid-1770s renovations also included two new outbuildings, which were connected to the house by colonnades, as shown in these photos. The building on the right was the kitchen, and it had three rooms on the first floor, along with a loft on the second floor. Like many kitchens of this period, it was separated from the main house as a fire safety measure. The building on the left was known as Servants Hall, and it had a design that matched that of the kitchen.. Although Washington did have slave quarters nearby, none of his slaves lived here. Instead, this building was used to house the servants – both black and white – of visitors to Mount Vernon.

George Washington lived here until his death in 1799, and Martha Washington died in 1802. They had no biological children together, so the estate went to his nephew, Bushrod Washington, who served for many years as a justice on the U. S. Supreme Court. The property was later inherited by Bushrod’s nephew, John Augustine Washington II, and then by John’s son, John Augustine Washington III.

Over the years, these later generations of the Washington family struggled to maintain the expensive estate, and in 1858 John Augustine Washington III sold it to the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association. Under their ownership, the mansion was restored, and in 1860 it was opened to the public as one of the nation’s first historic tourist destinations. The first photo was probably taken within a decade or two after this, and it shows the house as it would have appeared to a Victorian-era visitor.

Today, some 150 years after this photo was taken, the Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association continues to operate the property as a museum. The mansion and the two outbuildings that are shown here have been well-maintained throughout this time, and there is hardly any difference between these two photos. Mount Vernon was designated as a National Historic Landmark in 1960, becoming one of the first places to be recognized as such, and it remains a popular tourist attraction, drawing around a million visitors each year.