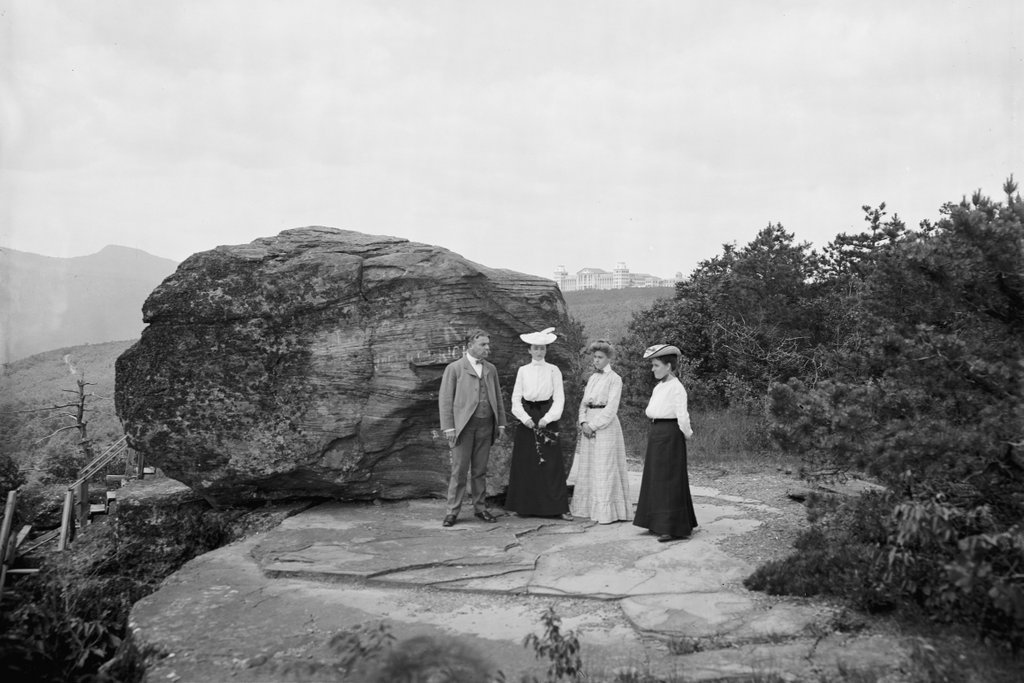

The Eyrie House on the summit of Mount Nonotuck in Northampton (now Holyoke), around the 1890s. Image from author’s collection.

The scene in 2021:

During the mid-19th century, mountaintop hotels became popular destinations here in the northeast. Prior to this time, Americans generally viewed mountains unfavorably, as they were poor for farming, they formed barriers to transportation, and their slopes often sheltered wild animals. Few colonial-era settlers had any interest in climbing simply for the sake of it, but this started to change in the 19th century, with writers and artists who increasingly portrayed the mountains as places of natural beauty, in contrast to the rapidly-growing industrial cities of the northeast.

This influx of visitors to the mountains led to the construction of many mountaintop buildings and hotels in the northeast. The first of these was built just a few miles from here in 1821, at the summit of Mount Holyoke. This building was little more than a refreshment stand, but it was eventually rebuilt in 1851 as a true hotel, named the Prospect House. It was subsequently expanded several times, and it still stands atop Mount Holyoke today as a rare survivor among the 19th century mountain houses in the region.

In the meantime, the Prospect House faced competition in 1861 with the opening of the Eyrie House on Mount Nonotuck, which is shown here in the first photo. Like Mount Holyoke, Mount Nonotuck is a part of the Metacomet Ridge, a nearly unbroken line of traprock mountains that extends from Long Island Sound to the Massachusetts-Vermont border. The highest peaks on the ridge are located in the Mount Tom and Mount Holyoke Ranges of Massachusetts, which are separated from each other by the Connecticut River. The river flows through a narrow gap between Mount Holyoke to the east and Mount Nonotuck to the west, providing dramatic views of the river and the surrounding valley from the summits of both peaks. The view from Mount Holyoke was immortalized by Thomas Cole’s famous 1836 painting The Oxbow, but Mount Nonotuck also offered a similar view from the opposite direction.

Mount Nonotuck is located at the northern end of the Mount Tom Range, where it rises about 820 feet above sea level and nearly 700 feet above the river valley. It does not appear to have had a formal name until 1858, when Edward Hitchcock named it after the old Native American name for what is now Northampton. Hitchcock was a prominent geologist and former president of Amherst College, and he was responsible for naming many local hills and mountains, including several on the Metacomet Ridge. He tended to prefer Native American names, and in some cases replaced inelegant English names, such as Hilliard’s Knob, which became Mount Norwottuck after the Native American name for Hadley.

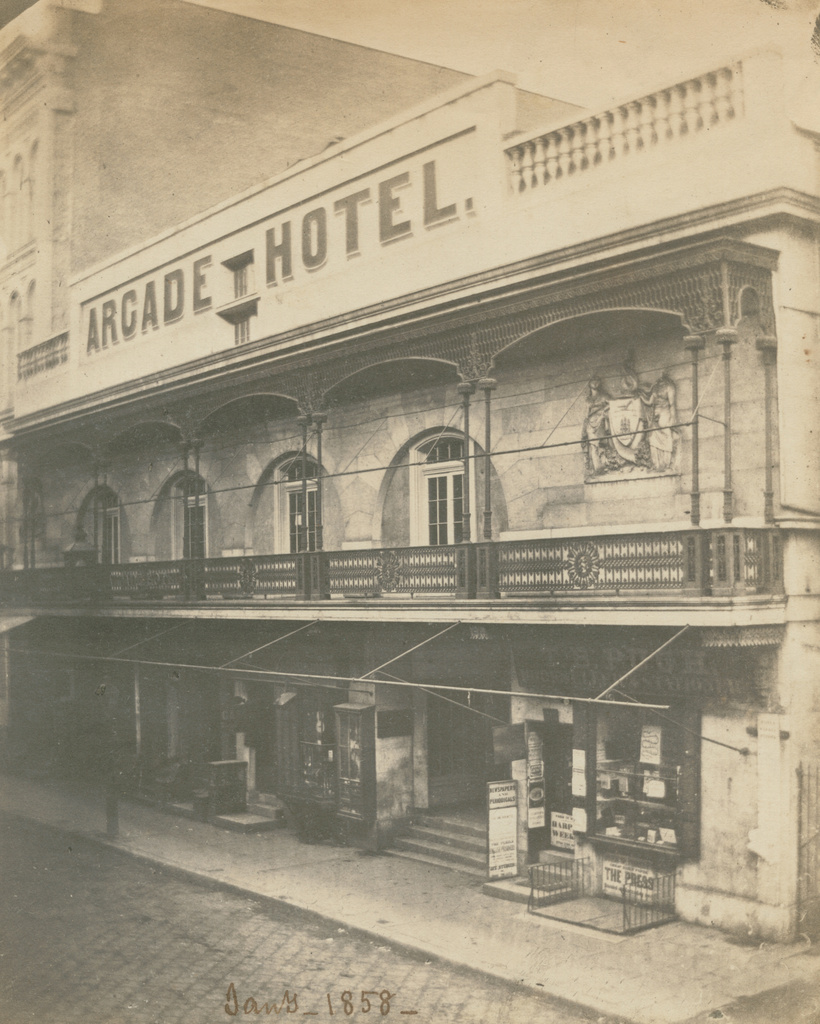

The “christening,” as newspapers described it, of Mount Nonotuck occurred on June 17, 1858, with a ceremony here at the summit. It was attended by Edward Hitchcock, who by this point had retired as president of Amherst College, and by his successor, William A. Stearns. About 500 other people gathered here, including dignitaries such as Lieutenant Governor Eliphalet Trask, Congressman Calvin C. Chaffee, and a number of local clergymen. Supposedly Henry Wadsworth Longfellow had also been invited, with the promise of naming the mountain “Hiawatha” in his honor, but he evidently declined, so the mountain became Nonotuck, which according to contemporary newspapers meant “mountain of the blest.” The formal honors of baptizing the mountain with the new name fell to Hitchcock, who scattered fragments of 12 stones that had been gathered from around the world, including specimens from the Alps, China, and Africa.

One newspaper account, published in the Massachusetts Spy, described how “[f]air women and brave men, toiled patiently up the steep ascent in a broiling sun, to enjoy the promised intellectual treat, breathe the pure mountain air, and drink in the extensive view.” Some of this is certainly embellished, as Mount Nonotuck is not exactly a difficult climb, yet it speaks to the motivations that drew mid-century New Englanders to the mountains. Similar articles appeared in newspapers throughout New England, and even in places as far away as Alexandria, Virginia.

It was perhaps as a result of the attention given to the newly-named mountain that, less than three years later, two local businessmen leased the summit area and built a small hotel in an effort to compete with the more established Prospect House across the river. The two partners, William Street and Hiram Farnum, sought advice from Edward Hitchcock on an appropriate name for their hotel, and he offered several suggestions. They ultimately chose Eyrie House, which according to Hitchcock’s memoirs was based on a line from John Milton’s Paradise Lost, which reads “the eagle and the stork on cliffs and cedar tops their eyries build.”

The building, which would later be expanded several times, was originally small and roughly square in its dimensions, with two stories topped by an observatory on the roof. This original portion of the hotel is visible in the distant center of the first photo, showing the cupola still atop it. Upon completion, the building featured five guest rooms, but in its early years it seems to have focused primarily on attracting day visitors. Unlike those who came here three years earlier and “toiled patiently up the steep ascent,” visitors to the Eyrie House could choose between riding up the carriage road, or taking the mile-long footpath directly from the railroad station to the summit.

The hotel was formally opened on July 4, 1861. Appropriately enough, Edward Hitchcock was one of the speakers at the dedication. The previous day, the Springfield Republican ran an advertisement for the festivities, which included the following description:

A good TELESCOPE has been purchased for the use of visitors of the house, and arrangements are making for suitable amusements.

A good Band will be in attendance through the day.

All Refreshments desired can be had at the house or on the grounds. . . .

Excursion tickets will be sold from Northampton, Holyoke, and all the stations on the railroad, to the mountain, and as no pains will be spared to make the occasion one of interest, it is hoped the public will avail themselves on this opportunity to spend a pleasant day in listening to patriotic speeches and enjoying the beautiful mountain scenery.

Admission to the Grounds on the 4th, free; to the House, 15 cents; children 10 cents.

After opening day, Street and Farnum raised the admission to 25 cents for adults and 12.5 cents for children, which was identical to the rates at the Prospect House. However, unlike across the river, where only paying customers could access the grounds, the Eyrie House grounds remained open free of charge, and guests only had to pay admission if they wanted to enter the building. The Eyrie House also offered special discounted rates for schools and other groups, and an 1861 advertisement assured readers that parties “would be furnished anything desired at reasonable terms.”

The Eyrie House was open daily, except for Sundays, throughout July 1871. However, in early August the two owners dissolved their partnership. The hotel and grounds were closed for several weeks, but William Street ultimately acquired Farnum’s interest in the business, and he reopened the hotel by the end of the month. He was only in his early 20s at the time, but he ran the Eyrie House for the next 40 years. During this time, he developed a reputation as both a successful hotelier and also an eccentric recluse. A lifelong bachelor, Street lived here on the mountaintop, where he was known for, among other things, collecting rattlesnakes with his bare hands and keeping them in a den for curious visitors to see. Over the years he studied other native wildlife, and gathered specimens, both living and stuffed, for his collection here.

Eccentricities aside, Street developed Mount Nonotuck into a popular destination. The Eyrie House never achieved the same level of success as its more established competitor on Mount Holyoke, but the hotel prospered throughout the 1870s and 1880s. He expanded the building in 1870, increasing its capacity with five more guest rooms, and in 1875 he purchased the property from his landlord. He subsequently built several more additions, eventually increasing the hotel to a total of 30 guest rooms. He also built long promenades extending to the north and south of the building, along with a smaller promenade at the front of the building facing west. Here at the summit, the grounds also featured a pavilion, stables, a croquet court, a picnic grove, and a swing.

By the 1880s, the Eyrie House offered orchestral concerts every day during the summer months, with the exception of Sundays. In 1880, admission still cost 25 cents, with another 25 cents for those who wanted a ride to the summit. Overnight lodging was $8 per week in August and $7 in September, or $1.75 per day. Meals were 50 cents each, and the hotel’s restaurant offered a wide range of food each day. For example, an August 1880 advertisement in the Springfield Republican listed the following menu for Fridays:

SOUP.—Beef.

FISH.—Baked Blue Fish, Cream Sauce.

ROAST.—Spring Chickens, Ribs of Beef.

COLD.—Corned Beef, Tongue, Ham.

VEGETABLES.—Sweet Potatoes, Mashed Potatoes, Beets, Onions, Corn.

RELISHES.—Pepper Sauce, Pickles, Mustard, Halford Sauce, Tomato Catsup.

PASTRY.—Mince Pie, Lemon Pie, Apple Pie, Cocoanut Pie.

DESSERT.—Peaches, Apples, Watermelons, Confectionery, Raisins Vanilla Ice-Cream, Tea, Coffee.

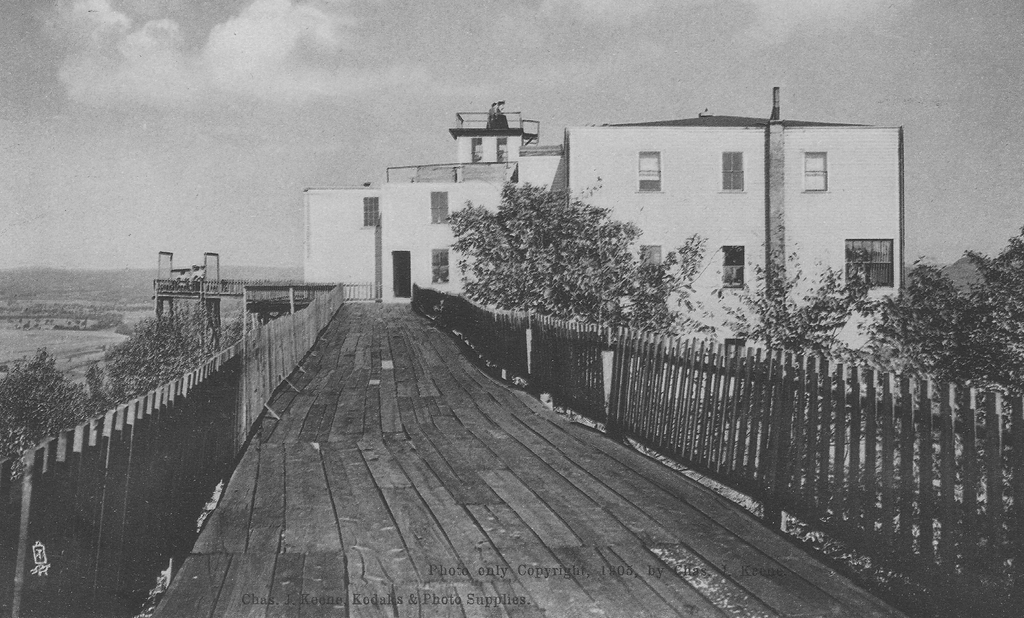

The first photo shows the building sometime around the late 1890s. It was taken from the south promenade, facing north towards the hotel. The original 1861 portion is visible in the distant center, with two women standing atop the observatory. Closer to the foreground on the right side is one of the newer wings of the hotel, and on the left side is the small front promenade. Beyond it is a glimpse of the view to the north, showing a portion of the river valley and the hills further in the distance.

Although this photo shows guests here enjoying the scenery, it also reveals the poor condition of the hotel and grounds. This is particularly evident here in the foreground, where many of the boards on the promenade appear to be in poor condition and portions of the fence are leaning inward or outward. Faced with declining visitors and an aging building, William Street embarked on extensive building project in 1893. His goal was to build a new stone hotel, which would be located immediately below the summit to the northwest of the existing building. Rather than taking a carriage road or footpath to the summit, guests would be able to ride to the top on an incline railway that would bring them directly into the ground floor of the new hotel.

Street worked on these projects in the mid-1890s, but he ultimately had to halt them because of financial troubles, perhaps as a result the economic recession caused by the Panic of 1893. Only a portion of the railroad grade had been completed by this point, and the stonework for the new building had not progressed beyond the ground floor. In the meantime, the old Eyrie House remained open, but it faced further competition in 1897 with the completion of the Summit House on Mount Tom, located about three miles to the south of here. Although not a hotel, this large building featured a restaurant, a stage, and an observatory. It was a much more substantial building than the deteriorating Eyrie House, and visitors could reach it by way of a mile-long trolley line that connected the summit to the Mountain Park amusement park at the base of the mountain.

As it turned out, the original Summit House would last just three years on Mount Tom, before being destroyed by a fire on October 8, 1900. It is impossible to say whether the loss of this building would have led to any substantial increase in business for William Street in the following year, but the Eyrie House ended up meeting the same fate just six months later.

Two of William Street’s horses had died at the summit during the winter of 1901, and it was impossible to bury them in the frozen, rocky ground here. He ultimately waited until the spring, and then decided to dispose of the remains by cremation. To that effect, he built a pyre about 50 feet from the barn and cremated the horses on the afternoon of April 13, 1901. At some point in the evening he left the fire unattended and went back to the hotel, about 200 feet from the barn. However, around 8:00pm he looked out the window and noticed that the barn was on fire. Making matters worse, the wind had shifted in the meantime, and was now blowing the flames in the direction of the hotel.

Street was alone on the mountain at the time. The first people to arrive here to help were Richard Underwood and his son William, who lived at the base of the mountain. They reached the summit around 8:45, but by this point one of the promenades was ablaze, and the flames had reached part of the hotel. However, their firefighting efforts had little effect, although they did manage to rescue a few items from inside the hotel, including the telescope. About an hour after the Underwoods arrived, a group of five men climbed up here, including an Easthampton firefighter. A few others later showed up, but there was little that they could do, and the Eyrie House was completely destroyed by 11:00pm.

William Street burned his hand while trying to fight the flames, but this was likely the least of his concerns in the aftermath of the fire. It was a significant financial loss, as he had only insured the Eyrie House for $2,000 of its estimated $10,000 value. In addition, the emotional toll was likely even worse for Street, who lost the place that had been his home and business for the past 40 years. Reporting several days after the fire, the Springfield Republican observed that he “appeared completely broken down by his loss. He had become greatly attached to his mountain home, and tears filled his eyes as he told of the loss he had sustained.”

Another article, published in the Republican the day after the fire, provided the following descriptions of Street and his hotel:

The old house, built originally over 40 years ago, was for years a popular resort in the days before the electric and cable roads made the southern promontory of the range easily accessible. There William Street, the picturesque hermit of the mountain, has lived for years, visited lately by few, and seemingly content to live in his lofty home apart from his fellow-men. The house formerly rang with the shouts and laughter of merry-makers, and the long dance hall was the scene of many gay parties in the days of the resort’s prosperity. Of late the house has fallen into decay and had presented a somewhat dilapidated appearance. . . .

William Street, the owner of Nonotuck, is noteworthy and individual;—there is nobody else like him. He has loved the mountain and his eyrie there, where for a great part of the year he has led a solitary life, which just suited him. He used to be fond of collecting various wild creatures to show his visitors, and his rattlesnake den, very carefully made on the north side of his old house, was an object of much interest, and had something to do with the popularity of it. He has lived so much in the midst of the forest that he knows a vast lot of things that happen therein, the ways of its denizens, the birds that have surrounded him so many springs and summers; the osprey’s nests he has seen, and the eagle he has personally become acquainted with. Mr. Street has become a silent man, as is the wont of those who dwell where more is said than meets the ear or can be put into words. But to those who appreciate the manner of man he is, he can discourse most interestingly. A tall, spare, rugged figure, absolutely careless of dress or grace of any sort, he is nevertheless worth knowing; and there are few who have seen him in his beloved Eyrie who will not sympathize with him in the destruction of the queer structure which has been his home so long.

The loss of the hotel was obviously devastating for Street, but he would soon lose the mountain itself as well. By the early 20th century, the state was eyeing the property as part of a proposed Mount Tom State Reservation, which would encompass much of the Mount Tom Range. They offered him $5,000 for his now-empty mountaintop property, but he refused, insisting on $25,000 instead. The state ultimately took the land by eminent domain, and deposited the $5,000 in a bank account in his name. In his later years he continued to live as a recluse, rarely receiving visitors or leaving his house in Holyoke, except for occasional trips to buy supplies every few months. He died in 1918 at the age of 80, supposedly without ever having touched the money that the state had given him for his land.

It is hard to say what exactly happened to the $5,000 that the state paid to William Street, but his property remains a part of the Mount Tom State Reservation nearly 120 years later. The days of croquet, concerts, and overnight lodging here on Mount Nonotuck are long gone, yet the mountain remains a popular spot for modern-day visitors, who are drawn here by the ruins of the hotel buildings and grounds. The most impressive ruins are the massive stone walls of the unfinished 1893 building, although these are located out of view in this particular scene, down the slope on the left side of the photo. Here at the summit area, the ruins of the original Eyrie House are a little less visible, consisting primarily of a few low stone walls and several pieces of iron embedded in the exposed rock at the summit. A portion of the building’s former footprint is now occupied by a beacon tower. It was built during World War II, and it is partially visible through the trees near the center of the 2021 photo.

Although the Eyrie House was located in Northampton, this site is now part of the city of Holyoke. For many years, the Mount Tom Range was part of an unusual exclave of Northampton, which was separated from the rest of the city by a narrow wedge of Easthampton. However, this arrangement led to disaffected residents of the Smith’s Ferry neighborhood at the base of the mountain, who believed that Northampton was failing to provide services for them. They successfully lobbied the state legislature to transfer the land, and in June 1909 it became the northern section of Holyoke.

Aside from the changes in ownership and jurisdiction, the other major difference here on Mount Nonotuck is the view. Once heralded as being the near-equivalent of the view from Mount Holyoke, the mountaintop is now almost entirely forested. There is a scenic overlook a little below the summit, at the end of a now-abandoned park road, but otherwise there are only limited views here at the site of the Eyrie House. Overall, though, this scene probably does not look all that different from how it would have appeared to Edward Hitchcock and the other attendees of the 1858 christening ceremony, before any buildings or other structures were added to the summit. Perhaps some of Hitchcock’s rocks from around the world are also still here on the summit, intermingled with the 150-year-old remains of the hotel and the 200-million-year-old basalt traprock of the Metacomet Ridge.