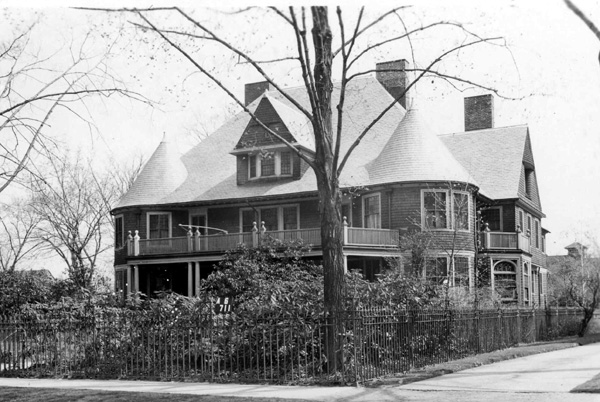

The house at 115 Dartmouth Terrace in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

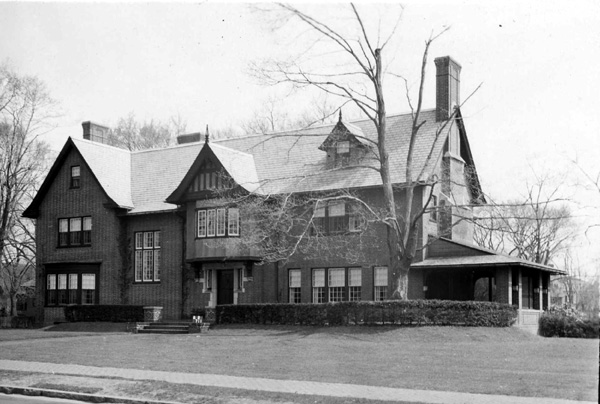

The house in 2017:

This house was built in 1888 for James and Ellen Cowan, on newly-developed Dartmouth Terrace. James was a coal dealer, and at the time the McKnight neighborhood was a fashionable area for the city’s leading residents. He lived here until his death in 1897, and by 1900 Ellen was still here with her daughter Mary, along with Mary’s husband George Sessions and their infant daughter Ethelyn.

By the 1910 census, Ellen was living elsewhere in the city with Mary and George, and this house on Dartmouth Terrace was home to Edwin and Ada Collins. Edwin’s occupation was listed as a waste dealer, and he lived here until his death in 1931, seven years after Ada’s death in 1924. The house was subsequently owned by Francis Wrisley, a telephone repair man. In the 1940 census, recorded shortly after the first photo was taken, he was living here with his wife Charlotte, son Francis, Jr., and Francis’s wife Elsie.

Today, much of the McKnight neighborhood has been restored to its original appearance, including this house. The vast majority of the 19th century homes in the area are still standing, and collectively they form the McKnight District on the National Register of Historic Places.