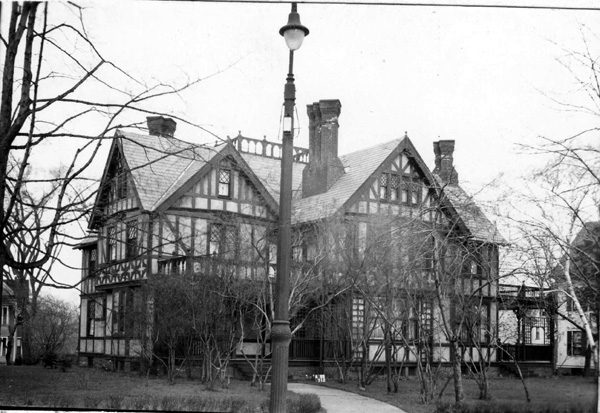

The house at the corner of Maple and Pine Streets in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The house in 2016:

This Tudor Revival mansion on Maple Street was built in 1899, and was the home of Henry G. Chapin, who lived here with his wife Susie, their children Katherine and Russell, and three servants. Henry was a Harvard graduate who worked as the secretary and later treasurer of the Chapin and Gould Paper Company. He lived here until 1917, when he was killed in a car accident on Allen Street, at the age of 57.

By 1920, the house was owned by Ambia C. Harris. She was the daughter of Daniel L. Harris, who had been a prominent civil engineer, railroad executive, and mayor of Springfield in the 19th century. Ambia never married, and spent much of her life at her parents’ house at the corner of Chestnut and Pearl Streets, but moved here to Maple Street when she was close to 60 years old. In the 1920 census, she was living here alone, except for two servants.

Ambia Harris died in 1925, and by 1930 her niece Corrine was living here with her husband, Frederick L. Everett, and their two teenage daughters, Jane and Sarah. Frederick was a physician, and their house was valued at $25,000, which was a considerable sum in the midst of the Great Depression. At the time, they also employed two live-in servants, Jane and Charles Long. They were a married couple who had immigrated from Scotland in 1907, and they worked as a butler and a cook.

Frederick and Corrine were still living here when the first photo was taken, but they died in 1948 and 1949, respectively. Their mansion is no longer a single-family home, although it still stands as one of the many historic 19th century homes on Maple Street. From this angle, the only significant change has been the front porches, which are now enclosed. Like the other houses in the area, it is located within the Ames/Crescent Hill District on the National Register of Historic Places, as well as the city’s somewhat overlapping Maple Hill Local Historic District.