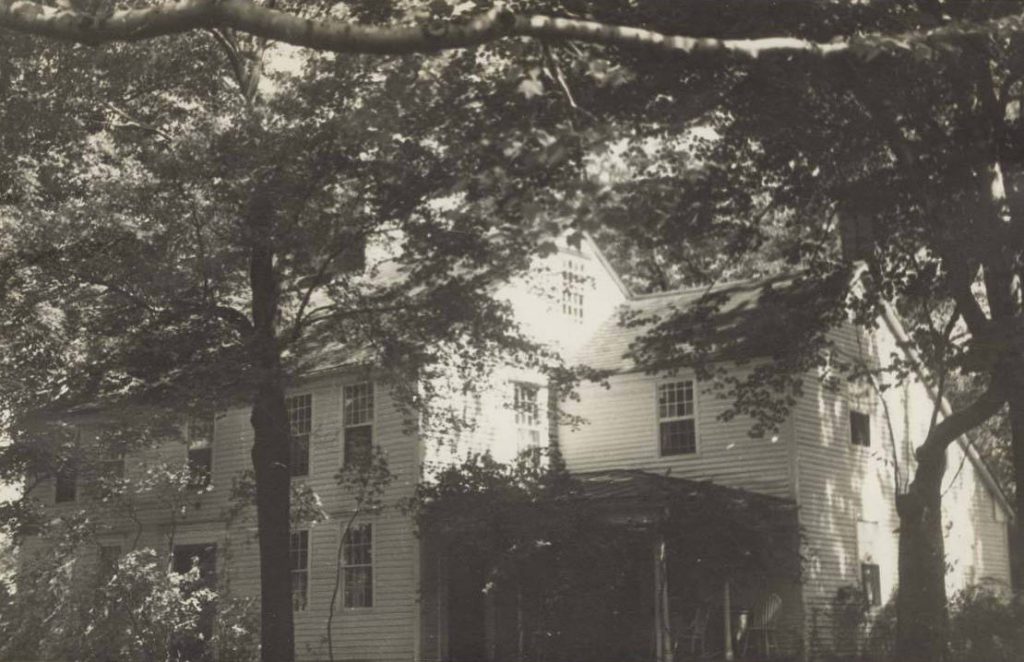

The Loomis Homestead, on the present-day campus of the Loomis Chaffee School in Windsor, probably taken around the turn of the 20th century. Image from Descendants of Joseph Loomis in America (1908).

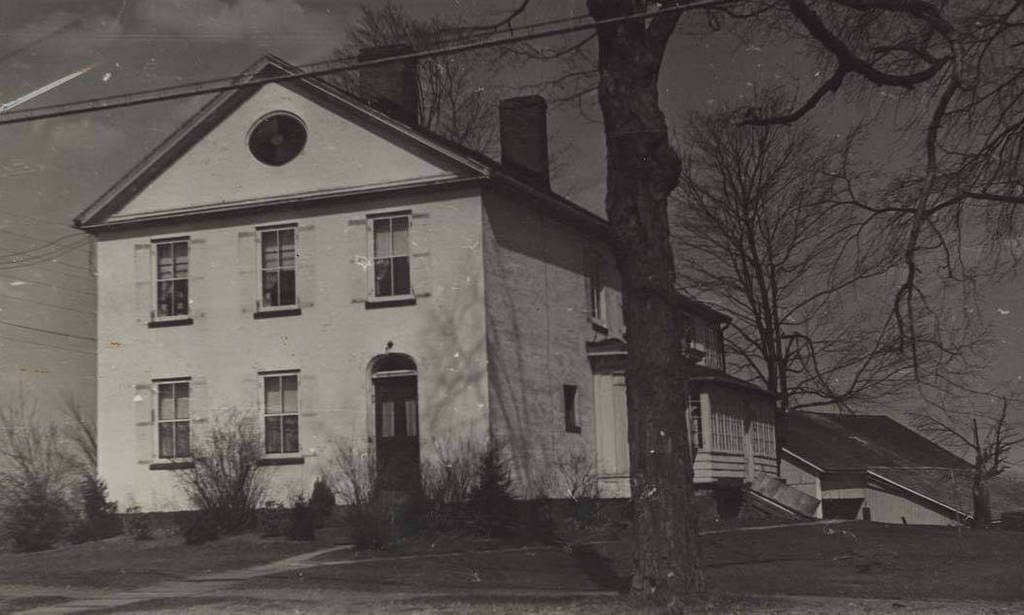

The house around 1935-1942. Image courtesy of the Connecticut State Library.

The house in 2017:

Built sometime between 1640 and 1652, this house is the oldest in Windsor, dating back to the first few years of the town’s settlement, and it is also among the oldest existing buildings in the country. The house was significantly expanded later in the 17th century, but the oldest section – the ell on the right side – was built by Joseph Loomis, one of Windsor’s original settlers and the patriarch of the Loomis family in America. Loomis was originally a woolen draper in Braintree England, but in 1638 he emigrated to the American colonies, along with his wife Mary and their eight children.

After a three-month voyage aboard the Susan and Ellen, the Loomis family arrived in Boston, and they lived nearby in Dorchester for the next year. However, in 1639 they joined a number of other Massachusetts colonists and relocated to the Connecticut River Valley. The following year, Joseph was granted 21 acres of land here in Windsor, located along the south side of the Farmington River, just to the west of its confluence with the Connecticut River. He built this house soon after, on a section of raised land that was known as “The Island,” because the surrounding meadows would often flood during spring freshets, effectively making the property an island.

Mary Loomis died in 1652, and Joseph in 1658, and their son John inherited the property. He had been about 16 years old when he and his family left England, and he lived here in Windsor until 1652, when he moved to Farmington. However, he moved back to Windsor in 1660, where he became a distinguished town citizen. He served as a deacon in the church, and he also represented the town in the Connecticut General Court from 1666-1667 and 1675-1687. John and his wife Elizabeth had eleven sons and two daughters, although only eight of their children would live to adulthood. Their only surviving daughter, Elizabeth, married Peter Brown, and they had a son, John Brown, who would become the great-grandfather of the prominent abolitionist of the same name.

According to the sign on the house, as well as other historical records, John Loomis built the main part of the house in 1688. He died the same year, but this addition was probably built for his son Timothy, who inherited the house and married his wife Rebecca the following year. They raised seven children here, and the youngest, Odiah, inherited the house. Odiah lived to be 88 years old, and after his death in 1794 he left the house to his son Ozias, who died two years later.

Ozias Loomis’s son, Odiah, was 12 years old when his father died, and he subsequently inherited the property, becoming the sixth consecutive generation to own this house. He and his wife, Harriet Allyn, had seven children, and, like his great-great grandfather Timothy Loomis, he represented Windsor in the state legislature, serving in 1818. However, he died in 1831 at the age of 48, and his youngest child, Thomas, inherited the house. Like his father, Thomas would also go on to be elected to the state legislature, serving in the lower house in 1857 and 1862, and in the state senate in 1874.

Census records from the late 19th century show Thomas Loomis as a prosperous farmer, with $20,000 in real estate in 1880. This included over 200 acres, although most of this was listed as unimproved woodland. He had 58 acres of meadows and orchards, and only two acres of tilled land, but in the year prior to the 1880 census his farm had produced 100 tons of hay, 624 pounds of butter, 800 dozen eggs, 80 bushels of potatoes, and 25 bushels of apples.

Thomas and his wife, Mary Jane Cooke, had two children, Allen and Jennie, although Allen died in 1884 at the age of 23. As a result, Jennie inherited the family homestead after her father’s death in 1895, becoming the eighth generation to own the house. However, Jennie was unmarried and had no surviving siblings, so in 1901 she transferred the house to the Loomis Institute, a private school that had been established in 1874 by five siblings from a different line of the Loomis family. The school itself would not open until 1914, but it was to be located here on “The Island,” where Joseph Loomis had originally settled in the 1640s.

The campus Loomis Institute, which later became the Loomis Chaffee School, was built just to the south of this house. Under the conditions of Jennie Loomis’s transfer of the house, she and her mother were allowed to live here for the rest of their lives. Mary Jane died in 1920, but Jennie was still living here when the second photo was taken around the late 1930s. She was actively involved with the school, serving as secretary of the Board of Trustees, and she lived here in this house until her death in 1944, about three centuries after Joseph Loomis had built the house.

The main section of the house underwent renovation in 1940, which included restoring the interior wood paneling to its original appearance. About a decade later, the older section was restored on both the interior and exterior, with the most noticeable change being the removal of the porch on the right side of the house. Otherwise, the exterior of the house has not significantly changed, and it remains a well-preserved example of 17th century saltbox-style architecture. It is still owned by the Loomis Chaffee School, and it stands as the oldest wood frame house in Connecticut, and the state’s second-oldest surviving building, after a stone 1639 house in Guilford.